Paris, Paris. The name evokes romance. Most who have visited this magical city are well acquainted with the sights and returning to favorite haunts is a full time passion. It would seem to most, however, that there is nothing new to discover, just favorites to revisit.

I would like to introduce you to pleasures hidden in plain sight —the covered passageways. These passages, an ingrained part of Parisian heritage, were first introduced in the late 18th century as a safe respite for shopping. Paris in that era was dark, dirty and inhospitable to most. There were no sidewalks, the streets were muddy and often flooded, a situation that was very discouraging. To promote shopping and bolster a nascent cafe society, enclosed passageways were designed and built throughout Paris; passageways that featured chic clothing boutiques, cafes and restaurants, bookstores and purveyors of delicacies. There were so many it was said that one could go from passageway to passageway in the rain without getting wet. The first was an immediate hit and spawned many others. Soon there were more than 150 throughout central Paris. Today only 20 remain, most if not all on the right bank, with the degree of luxury dependent on location.

Most of these ancient shopping malls have labeled archways announcing their presence. But you must look for them as they are usually squeezed between commercial buildings.

Palais Royal

The prototype of these arcades was in the courtyard around the Palais Royal near the Louvre. Owned by Louis Phillipe, cousin of Louis XVI, and rich beyond measure, he was, nevertheless, in constant need of money. A shopping arcade wrapping around three sides of the palace gardens was proposed and he jumped at the opportunity. Although the original structure, started in 1786, was torn down (perhaps a metaphor for Louis Philippe’s own demise during the revolution), the current sophisticated arcade was reconstructed in 1829. Today, that arcade remains accessible through the garden and protected on all sides by an imposing gold-topped black metal “fence” separating the gallery sidewalks from the foliage. I would recommend this as your first stop. Not precisely a passage, it is more like a protected arcade, an outdoor ground floor to the official ministerial buildings above it. Tour all three sides and you’ll find avant-garde clothing boutiques catering to today’s “flaneurs,” contemporary art galleries, shoe shops, both classic and outrageous, and, significantly, Le Grand Véfour, the formerly Michelin-starred restaurant, opened in 1784 and still serving. Entering via Rue de Montpensier will take you to the courtyard via the Comédie Française.

Galerie Véro-Dodat

Paradoxically, this very upscale arcade was started in 1826 by two butchers. Today it is home to Christian Louboutin, antique furniture stores, sculpture galleries, decorative arts, fine arts and cafés. The immaculate tiled floors and ornate lamps maintain its aura of 19th-century luxury. Accessed from the ironically named Rue du Jean Jacques Rousseau, the Enlightenment writer who wrote “Discourse on Inequality” and “The Social Contract,” and the tony Rue St. Honoré, it is located adjacent to the Bourse de Commerce, the old Commodities Exchange built in 1763 and now the home of billionaire François Pinault’s art collection (yet more irony for the ghost of Rousseau).

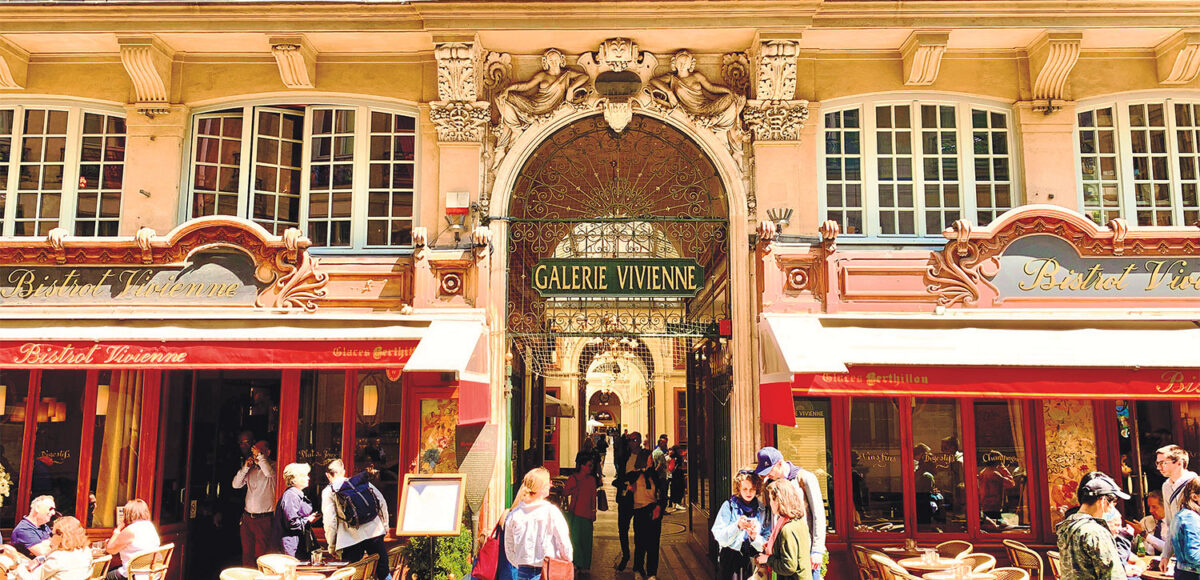

Galerie Vivienne

Virtually across the street from the gardens and arcades of the Palais Royal you will find a vibrant, still thriving, sophisticated shopping arcade built in 1826.

Anchored by the Legrand Filles et Fils wine shop, it began life as a tea and spice store in 1880 by François Beaugé. Pierre Legrand bought the establishment and founded his wine boutique after the First World War. It is said that Pierre invented the profession of wine curator, selling wine and educating the public about them. It passed from generation to generation until recently when the Legrand family sold a majority stake to a commercial group. Still, much of the original enterprise remains including the beautiful wooden bar and fixtures. Not the oldest wine shop in Paris, it is still considered one of the best. They offer a large selection from their cellar as well as the opportunity to sample rare vintages. Climbing the stairs to the first floor, look up and see the ceiling insets made of wine corks designed and executed by Pierre after buying the establishment. Like the original store, it is here that you will find their selection of fine caviar, foie gras and smoked fish. If you were to follow the spiral stairs up another floor you would find yourself in the original living quarters of the Legrand family, now used as business offices.

Proceed a few yards down the hall and you will find the Librairie Jousseaume, one of the original tenants of Galerie Vivienne. Originally opened in 1826 and passing from one owner to another until 1890 when the Jousseaume family bought it. It is now being run by the fourth generation, François Jousseaume. The bookstore has been well kept up but there is nothing left of the original, save the layout. Jammed to the rafters with used books, both rare and current, M. Jousseaume reigns over his bookstore. Not particularly interested in answering questions, he thrust a gently used copy of Patrice de Moncan’s 2012 book entitled “Literary Promenades: The Covered Passageways of Paris,” an indispensable guide if you want to read about what Charles Baudelaire or Colette had to say about their contemporaneous wanderings in the various passageways; not so much if you’re trying to discover the actual history of these hidden gems. M. Jousseaume was more forthcoming when he found out that this article was for the “Beverly Hills Courier.” He wanted to know all about what he called the “city of millionaires.”

Galerie Colbert

Adjacent to Vivienne, this arcade, crowned with an enormous glass dome in the entryway with its bronze sculpture below, used to be bustling with shops. Now it is primarily a branch of the National Institute of Art History, its boutique spaces used as classrooms for the Sorbonne. All that remains of the boutiques are the placards above the rooms indicating what used to be there. Next door is the restaurant Le Grand Colbert. Originally built in 1637 and eventually sold to Jean Baptiste Colbert, Louise XV’s Minister of State, it passed to the aforementioned Philippe d’Orleans in 1719 and then to the state in 1825. The original building was destroyed to make way for the Galerie in 1828 but was rebuilt and opened as a store. It became a restaurant in 1900. Renovated in 1985, you can still find some of the original mosaics on the ground. It was used as a primary location in the 2003 film “Somethings’ Gotta Give’’ starring Jack Nicholson, Keanu Reeves and Diane Keaton, causing a tourist rush that has calmed and now, once again, it is a sophisticated Parisian lunch spot. Ironically, it’s right next door to a student cafeteria.

Passage Choiseul

Close by, on the other side of the National Library and not far from the Opera, is the Passage Choiseul. Built between 1826 and 1827, it’s bustling with young people, there for the inexpensive, street food restaurants. Beautifully restored, it sports a peaked glass ceiling, popular in the day, and the longest corridor of any of the remaining passages. At the end of the passage is the Théatre des Bouffes Parisiens founded in 1855 by Jacques Offenbach for his operettas. From 1986 to 2007 actor Jean-Claude Brialy was the director. Today it features comedy shows.

Passages des Panoramas

Walking north to the area called Les Grands Boulevards, a more working class area on the south side of Boulevard Montmartre, is the oldest (1799) and perhaps most famous passageway. Narrow like Choiseul, its location and that of its neighboring Passage Jouffroy is, ironically, where Boulevard Haussmann becomes Boulevard Montmartre. Ironic because it was Haussmann who began to rebuild the streets and neighborhoods of Paris in 1854, modernizing them, widening the boulevards and putting in sidewalks. With these improvements came the modern Parisian department stores like BHV (1855), le Printemps (1865) and Galeries Lafayette (1894). It was the very nature of these improvements and the competition from the larger stores that doomed the passages.

The Passages des Panoramas’ narrow corridor and beautiful tiled floor is full of restaurants but no tables for seating. Signs above the doorways indicate the original stores, but none remain. This is where the Stern engravers set up shop in 1834 and passed down through multiple generations until it closed and became a deluxe café. It had been the oldest existing engraver in Paris and Mme. Stern ran the store well into her 80s. In a conversation with her almost 20 years ago, she lamented that this store, run continually by a family member since its opening, would have to be sold because none of her children were interested in carrying on. While giving me the history of her wonderful shop, she stopped momentarily to greet one of her neighbors, the director of the adjacent Théatre des Variétés. That director? Jean-Paul Belmondo. He ran the theater from 1991-2004. The theater, originally in the arcades of the Palais Royal, moved to the Passages des Panorama in 1807 where it has been in continual use. Before Offenbach started his own theater, he premiered his works here.

Even with fewer shops, the Passages des Panorama is part of history. It was here, in 1834, that gas lighting was used for the first time. The peaked glass roof, the old gas fixtures and the wooden boutique entryways remain along with the memories and, of course, the prerequisite bookstore, a fixture in almost all the passages.

Passage Jouffroy

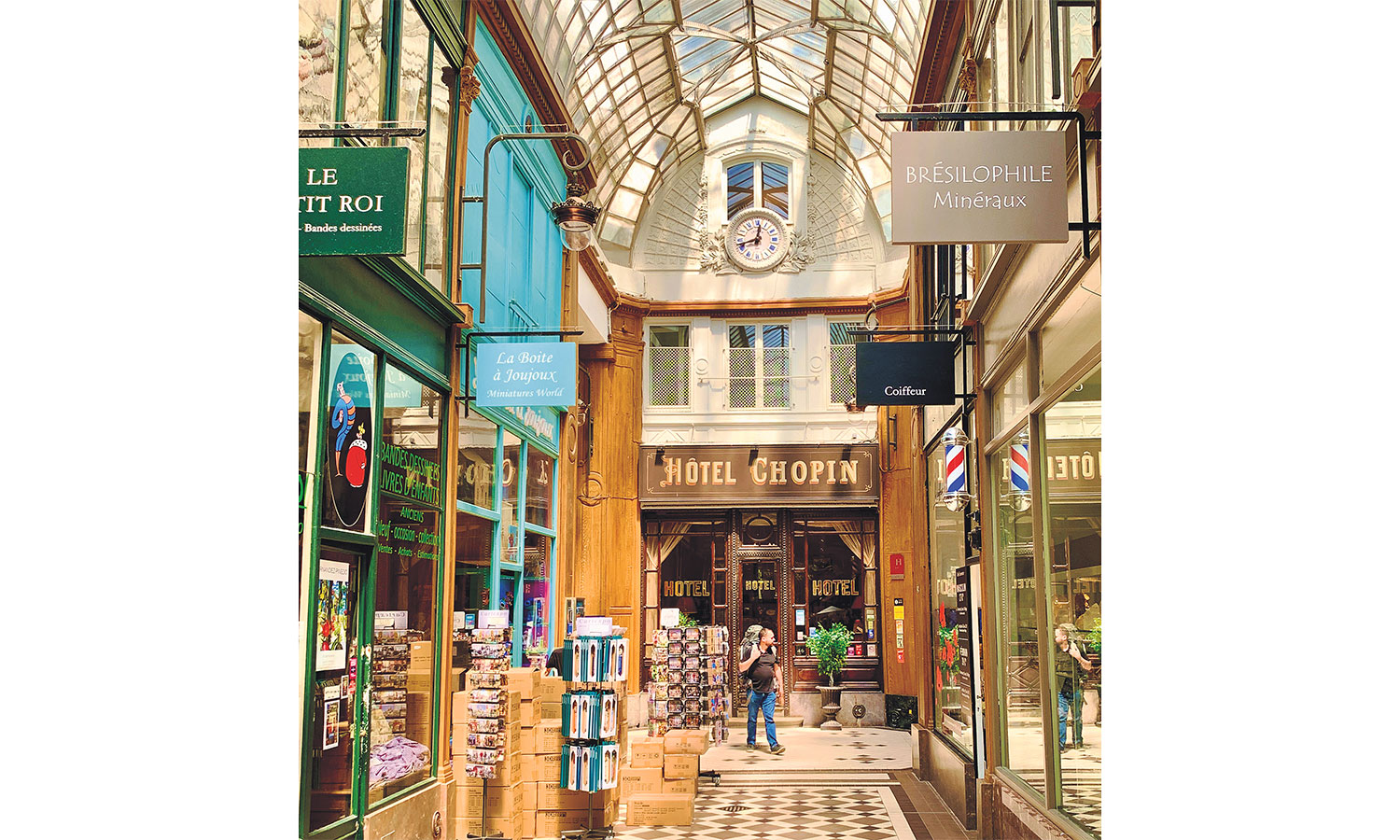

Directly across the Boulevard Montmartre is the Passage Jouffroy. Built in 1845 to capitalize on the popularity of the Passage des Panoramas, it houses the Musée Grevin, Paris’s answer to Madame Tussauds of London. Built in 1882 it specializes in wax recreations of horrific crimes and scenes from the French Revolution; the modern montages and figures are considerably less interesting. The highlight of the museum, architecturally speaking, is its street-facing separate Art Nouveau entrance.

At the end of the first corridor is the little Hotel Chopin. It opened in 1846 and is one of the oldest hotels in Paris. Originally called the “Family Hotel” it changed names in 1970 in honor of Chopin who, rumor has it, would meet George Sand there. Full of small boutiques and significant art galleries, there is a very large bookstore that has been there since the opening of the passage.

Short on time? After a visit to the Louvre, step into the gardens of the Palais Royal to see the courtyard laid out with short columns of different sizes conceived and constructed by Daniel Buren, then continue on to the arcades. Consider it dipping your toes into les passages de Paris.

Neely Swanson spent most of her professional career in the television industry, almost all of it working for David E. Kelley. In her last full-time position as Executive Vice President of Development, she reviewed writer submissions and targeted content for adaptation. As she has often said, she did book reports for a living. For several years she was a freelance writer for “Written By,” the magazine of the WGA West, and was adjunct faculty at USC in the writing division of the School of Cinematic Arts. Neely has been writing film and television reviews for the “Easy Reader” for more than ten years. Her past reviews can be read on Rotten Tomatoes where she is a tomato-approved critic. For the past few issues, Swanson has contributed pieces about her travels in London and Paris.