“I’ve Been to the Mountaintop” is the last speech delivered by Martin Luther King Jr. the day before he was assassinated in Memphis, Tennessee. Katori Hall’s Olivier-winning play, “The Mountaintop,” was first produced in 2010 and is now at the Geffen Playhouse. Taking its title from this speech, delivered in support of city sanitation workers on April 3, 1968, we meet the exhausted preacher in the wee hours of April 4 in room 306 of the Lorraine Motel in Memphis. We know what he doesn’t—this will be his last day on earth. Settling in for the night as a storm rages outside, literally and metaphorically, he wants, no, needs a cigarette; Pall Malls to be precise. He’ll settle for a cup of coffee from room service. No more room service, he’s informed. He’s desperate. Just a simple cup of coffee. Moments later, like an apparition, Camae in full housekeeper regalia, appears at his door. Tall, composed, refreshingly direct, she walks into the room, silver tray in hand, like, as has been said, she was walking onto a yacht. They banter, she flirts, he approaches too close, they separate like they were in a boxing match and she was Muhammed Ali playing rope-a-dope.

Hall has set up this imagined encounter to illustrate the breadth and depth of King, including his frailties, especially when they came to the temptations of the flesh; his self-doubts, his dreams and despairs, and especially his doubts. Hall’s scenario sets him up using his own words:

“And He’s allowed me to go up to the mountain. And I’ve looked over, and I’ve seen the Promised Land. I may not get there with you. But I want you to know tonight, that we, as a people, will get to the Promised Land. And so I’m happy tonight; I’m not worried about anything. I’m not fearing any man. Mine eyes have seen the glory of the coming of the Lord.”

Camae, underestimated by all, including King, knows what’s what and listens intently. She is, in her right, a philosopher, surprisingly knowledgeable about the history of the movement and at turns, can espouse Malcolm X’s and Fred Hampton’s positions cogently, an irony surely not missed as Malcolm had already been killed and Fred would be assassinated the next year. King, like most men confronted with something so statuesque and seductive, consistently focuses on her parts rather than the whole until…her awareness hits him like one of the lightning bolts outside. Camae hides a secret and to reveal it would reduce the surprise and ultimate philosophical questions behind this play. The story itself is a good one; the subtext is better.

At a fast-moving 90 minutes (without intermission), this dramatic and often funny imaginative piece about what may have been going on in King’s mind before he was to meet the aforementioned Lord, raises more questions than it answers. It is King who is on full display, warts and all, and Camae who is our guide. She is sly, deceptive as much as she is perceptive. He is dedicated, distracted, arrogant and vulnerable. That she is very tall and he is very short is both a source of humor and of drama.

As they say, it’s all on the page. There are weaknesses but none, as far as I’m concerned, with the play itself. Creative, fast-moving, effectively philosophical on all things of the soul, it does place a burden on the two actors who are on stage throughout. Camae, a figure of the imagination, literally and figuratively, is more open to interpretation. Whatever the actor brings to it can be believable provided she convinces us of her verisimilitude. On the other hand, with King, the actor is already burdened with the audience’s suppositions because we know his story; we’ve heard him and we know what comes next. Still, the actor benefits from some of these expectations provided he comes within the target.

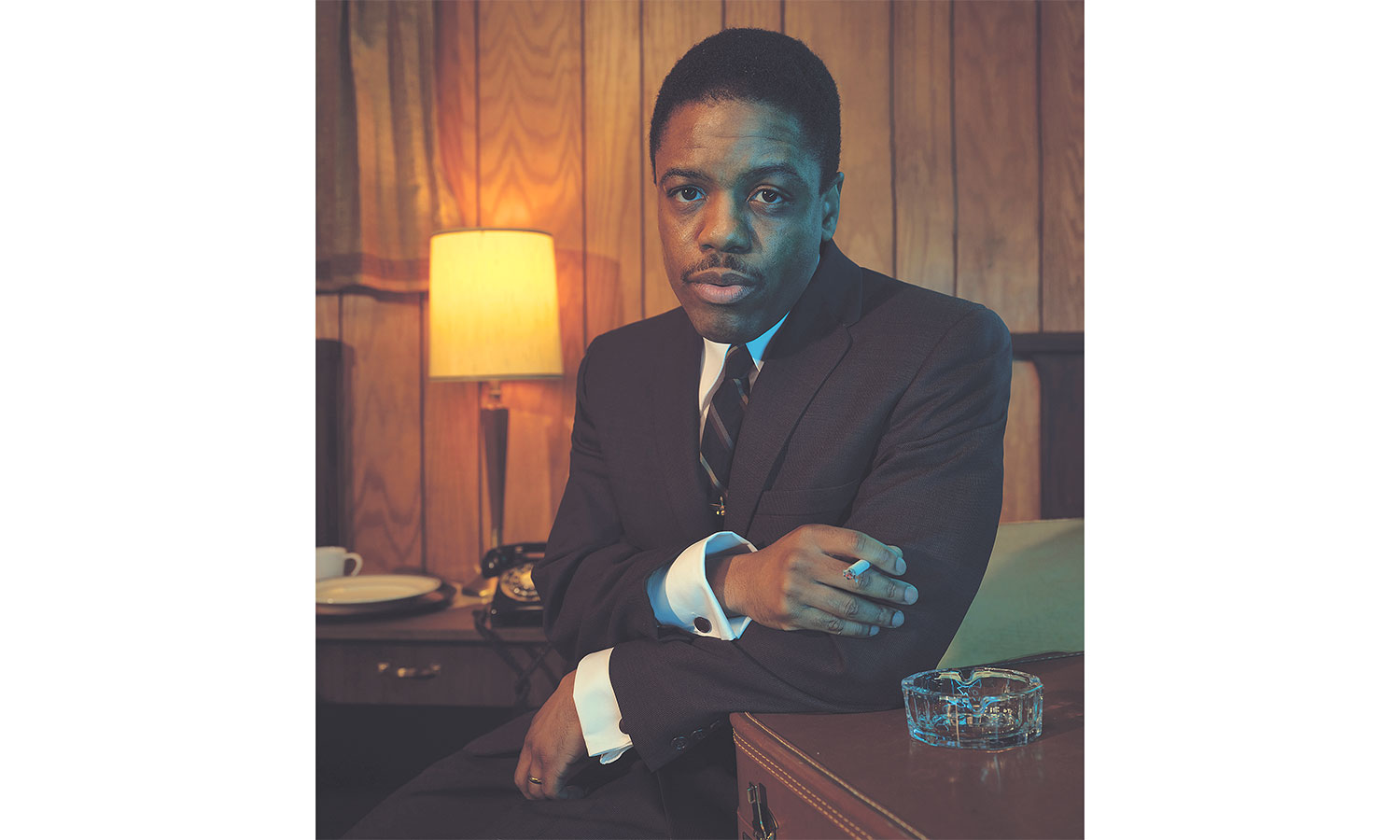

Jon Michael Hill, King, is an experienced actor with credits on Broadway and the Public Theater. A member of the Steppenwolf Theatre Company in Chicago, his breakout performance was in “Superior Donuts,” which yielded him a Tony nomination when it transferred to Broadway. Having seen him in this production when it premiered at Steppenwolf, I was looking forward to what he would do here. The report card is mixed. He is best when displaying rage, compassion and fear, moments closely related to the man who gave the speeches. He is less effective in displaying vulnerability and is weak when revealing his cravings of the flesh. When called upon to make a pass at Camae, he is awkward and unconvincing. It was King’s dalliances that were fodder for the FBI in trying to discredit him and it is unlikely that he was any less effective as a ladies’ man than he was as an inspirational speaker. Expressing King’s vulnerability does not seem to be in Hill’s wheelhouse. This is truly a shame because the play is written as a duel of spiritual equals and it’s weakest when Hill’s King cannot keep up with Camae.

Amanda Warren, Camae, is a wonder. She has a shaky beginning, trying to find the right tone for her character. When an actor plays everything at the top register, nuance is tossed and there is nowhere to go in moments of passion, anger or excitement because that range has already been exhausted. This was Warren at the start and her bellowing masked over the vulnerability and/or awe her character might have been feeling. When she eventually took her vocal pyrotechnics down a register, she really started to cook and from that moment on, she owned the play. Her ability to express a full range of emotions drew all of our focus throughout most of the action. Luckily, Hill found the right notes at the end and the spiritual battle between Camae and King is of two titans; one you’ve come to know, the other you thought you did.

Patricia McGregor directed. The Artistic Director of the New York Theatre Workshop, one of the most prestigious off-Broadway theaters, McGregor has a well-rounded resumé; nevertheless, many of the weaknesses cited could be the fault of the director. Hill’s awkward and unconvincing attempts at seduction is one example and Warren’s initial over-the-top vocal fireworks at the beginning is another. McGregor’s vision of how to stage this play is, however, faultless, and Rachel Myers’ set is, in itself, a character in this play.

“The Mountaintop” is definitely worth seeing, especially for the questions it asks and the answers it doesn’t give. This is a play that makes you think; it makes you remember how far we’ve come and how far we have yet to go. It’s time well spent.

At the Geffen Playhouse through July 9. Performances are on Tuesdays through Saturdays at 8 p.m. with matinees at 3 p.m.; Sundays at 2 p.m. and 7 p.m. The play is 90 minutes with no intermission.

10886 Le Conte Avenue

Los Angeles, CA 90024

Neely Swanson spent most of her professional career in the television industry, almost all of it working for David E. Kelley. In her last full-time position as Executive Vice President of Development, she reviewed writer submissions and targeted content for adaptation. As she has often said, she did book reports for a living. For several years she was a freelance writer for “Written By,” the magazine of the WGA West and was adjunct faculty at USC in the writing division of the School of Cinematic Arts. Neely has been writing film and television reviews for the “Easy Reader” for more than 10 years. Her past reviews can be read on Rotten Tomatoes where she is a tomato-approved critic.