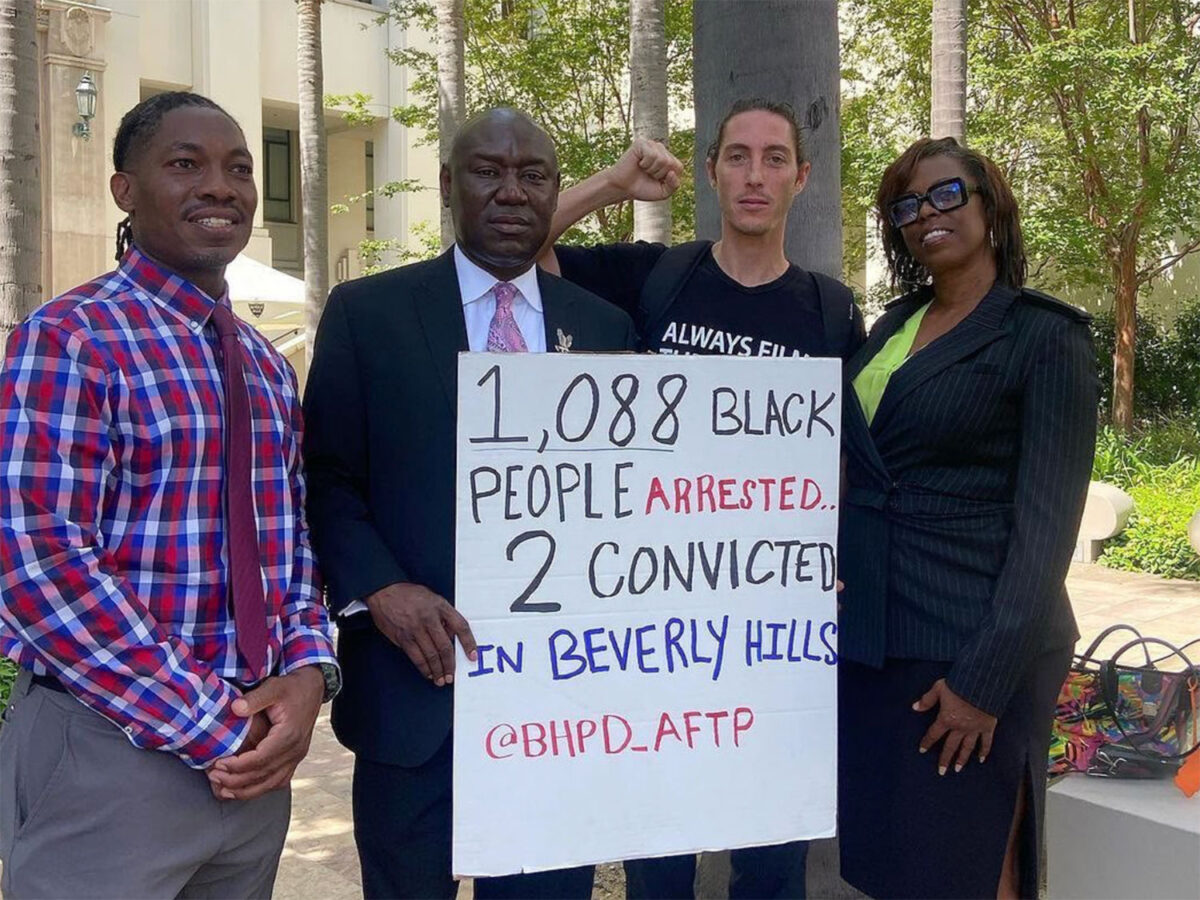

Beverly Hills has decided to join 12 other cities in a lawsuit that seeks to postpone implementation of the Los Angeles County Superior Court’s new “zero-bail” policy, which eliminates cash bail for most felonies and misdemeanors.

This decision was made during the City Council closed session on Oct. 3, Public Information Officer Lauren Santillana told the Courier.

The zero-bail policy was enacted on Oct. 1 to address what court officials say are unfair and damaging consequences of pre-arraignment jail stays for people who cannot post bail. It requires most nonviolent offenders to be automatically cited and released—or, in the case of more serious offenses, released on terms determined by a magistrate—within 24 hours of being arrested.

“A person’s ability to pay a large sum of money should not be the determining factor in deciding whether that person, who is presumed innocent, stays in jail before trial or is released,” LA Superior Court Presiding Judge Samantha Jessner said in a statement announcing the new rules.

Critics, however, worry that eliminating most pre-arraignment jail stays will lead to an uptick in crime.

Whittier, Arcadia, Artesia, Covina, Downey, Glendora, Industry, Lakewood, La Verne, Palmdale, Santa Fe Springs and Vernon filed a lawsuit on Oct. 2 seeking an injunction to delay the implementation of the new bail schedule.

“Our top priority as a local government is to keep people safe,” said Whittier Mayor Joe Vinatieri in a release announcing the lawsuit. “It’s getting harder and harder to ignore the problems our communities are facing, and what happens when breaking the law doesn’t get you in trouble.”

Beverly Hills Chief of Police Mark Stainbrook told the Courier he is troubled by recent crime trends but is committed to following the law.

“The rise in violent and property crime in Los Angeles County is a concerning development, but the Beverly Hills Police Department will work with LA Superior Courts, the Sheriff’s Department, the District Attorney’s Office and our regional law enforcement partners in order to provide the best service and protection we can under this new mandate,” he said.

Advocates of the zero-bail policy say that the concerns raised by opponents are based on fear, not fact.

“This is a policy based on the scientific consensus that moving away from money bail systems makes communities safer,” Micah Clark Moody, investigative fellow at Civil Rights Corps, told the Courier.

“Putting people in jail for just a few hours is enough time to destroy housing, work, family structure, and medication routines they’ve established,” she added.

Civil Rights Corps is one of several advocacy groups that filed a lawsuit seeking to reinstate the pandemic-era practice of citing and releasing most nonviolent offenders. This policy was intended to limit the spread of COVID-19 during pre-trial jail stays, but advocates say it also increased community safety and well-being.

Their lawsuit successfully forced the Los Angeles Police Department and the Los Angeles Sheriff ’s Department to reinstate the COVID-19 emergency bail schedule. The new Superior Court decision expands these limited cash bail practices to all law enforcement departments in LA County.

The Bail Project, a national nonprofit organization dedicated to fighting cash bail policies and providing bail assistance, issued the following statement on the recent changes to LA’s bail system:

“When people are jailed before trial due to unaffordable bail, they are needlessly separated from their families and communities, stand to lose their jobs and homes, and are forced to face the unsanitary, traumatic, and often fatal conditions in county jails. This is precisely why the courts found the previous paradigm unconstitutional and required the county to modify its procedures.”

A key difference between the county’s new bail schedule and the emergency COVID-19 bail schedule is the addition of magistrate review for certain serious crimes.

In this process, a magistrate may impose additional release terms—such as text reminders about court appearances, check-ins with court staff, home supervision and electronic monitoring—on offenders of serious crimes.

Several highly violent crimes–such as domestic battery, manslaughter, rape, murder, and most types of assault–will still require detainees to post cash bail.

“With the implementation of the new Pre-Arraignment Release Protocols,” said David Slayton, executive officer/clerk of court, “the Court is helping to develop a robust and dynamic pre-arraignment release system for non-violent, non-serious felonies and misdemeanors that prioritizes public and victim safety and equal access to justice for all.”