Many sirens of the silver screen have called Beverly Hills home. One of the first A-listers, Mary Pickford, took up residence on Benedict Canyon Drive. Greta Garbo, Ava Gardner and Marlene Dietrich lived on North Bedford Drive. While each of these legends has made major contributions to the world of motion pictures, and their influence on pop culture and beauty cannot be denied, there is only one actress whose influence has quantifiably changed our modern world—Hedy Lamarr.

During the height of her fame in the 1940s, Lamarr surreptitiously invented the technology that would make Wi-Fi, Bluetooth, GPS and cell phones possible.

However, it would take decades before she would receive recognition for her contribution. For Lamarr, her legendary beauty was a blessing and a curse. Many would not accept that “the most beautiful woman in the world,” as she had been called, could have brains, too.

Lamarr was born Hedwig Eva Kiesler in Austria, Vienna in 1914 to assimilated Jewish parents. Though Louis B. Mayer, studio head at Metro-Goldwyn Mayer (MGM), had given Hedy her big break and her new name, she was forbidden, as were all MGM contract actors, from speaking about religion. Hedy kept the secret so close that her children whom she had with her third husband (out of six), actor John Loder, never knew she was Jewish until after her death.

While under contract at MGM, (Lamarr dazzled in celluloid classics like the 1938 film “Algiers,” “Ziegfeld Girl” in 1941 and Cecile B. Demille’s biblical epic “Sampson and Delilah” in 1949), she began inventing as a hobby. There is not much in the public record about what drove her to invent or even how she did despite her education, the sum of which was middle school and a spell at a Swiss finishing school for girls. Like so many women of her generation, college was not in the cards. Not that she would’ve attended; her sights were firmly set on acting. She quit the boarding school to pursue her dream.

Yet the record shows she did invent. Lamarr told Merv Griffin on an appearance on his TV program in 1969, “I was different, I guess. Maybe I came from a distant planet, but whatever it was, inventions came easy for me.” Thomas Alva Edison had no formal education at all and thanks to him we have the lightbulb. The idea is the thing. And Hedy had a lot of ideas.

She also had a lot of time on her hands to think of them, especially in the evenings after a day on the set. Hedy didn’t like the Hollywood scene, she didn’t drink and loathed going to parties. Instead, she preferred to sit at her home on Roxbury Drive and work on her inventions. The star had a drafting table and light, and all the necessary accouterments installed at her residence and spent her evenings sketching out her ideas. Howard Hughes, with whom Hedy had a close relationship, gifted the actress a miniature version of her home setup. This was put in Hedy’s movie trailer so she could continue her work in between takes. She is also said to have sent Hughes sketches while he was working on building the fastest plane in the world. Lamarr claimed she bought books on the fastest birds and the fastest fish and cobbled the best parts of both in her drawing to Hughes. And, though the implementation of her idea took engineers to connect a few dots, Hedy’s basic concept worked and influenced the design.

Mostly, what we know of Hedy’s inventions during this time is that they were largely inspired by World War II, which was already raging in Europe by 1940. She attempted to create a tablet (akin to Alka-Seltzer) that would turn water into Coca-Cola for servicemen overseas. Even with the help of two chemists that Hughes had lent her, Hedy couldn’t get it to work.

Photo Courtesy of Employee(s) of MGM, Public domain,

via Wikimedia Commons

At one of the rare Hollywood parties she did attend, Hedy met George Antheil. He was an accomplished composer who had come to Hollywood with his wife in the hopes of scoring movie soundtracks. George also had experience working as a certified inspector of artillery ammunition at a U.S. armory in Pennsylvania. Hedy’s first husband owned a munitions factory in Austria, and she would often listen in on his discussions with German military officials who came to their home. This common interest is what likely drove Hedy and George to strike up a friendship, according to Pulitzer Prize-winning author Richard Rhodes, who spent years researching “Hedy’s Folly,” the definitive book on Lamarr’s inventions. “I think Hedy looked around and when she heard of George’s ammunitions background, she just said, ‘You’ll have to do.’” And Lamarr was relentless in pushing her ideas forward. George said of Hedy, “All she wants to do is stay home and invent things…She calls in the middle of the night because some idea hit her.” For Lamarr, in George she had finally found someone who was willing to look past her looks and listen to her. She once told a reporter, “A man does not try to find out what is inside. He does not try to scratch the surface. If he did, he might find something much more beautiful than the shape of a nose or the color of an eye.”

Lamarr and Antheil designed three inventions during their partnership, but one would change the world.

Outraged by the German U-boats that marauded the Atlantic, targeting passenger vessels and killing all on board, Hedy was desperate to find a way to stop them. Her initial idea was for a radio-controlled torpedo. Then, realizing an enemy could simply intercept the signal and divert the missile, she came up with the idea of frequency hopping. If the torpedo was guided by a radio signal and that signal would constantly and randomly switch frequencies, an enemy wouldn’t be able to intercept it, not long enough to change the course of the weapon before the frequency shifted again.

Lamarr enlisted Antheil to put her idea into practice. They worked long hours together, so much so that Hedy offered him and his wife to move into her house to expedite the completion of the patent for their invention. But when Antheil’s wife came to visit and saw that every window in the house overlooked the pool, she asked him if Hedy swam in it. She did, and legend has it Lamarr preferred to do her laps in the nude. That put a quick end to the matter. Antheil would stay in Hollywood, with his wife. Though there is nothing to suggest there was ever a romantic relationship between George and Hedy, it’s not difficult to see why Antheil’s wife put her foot down.

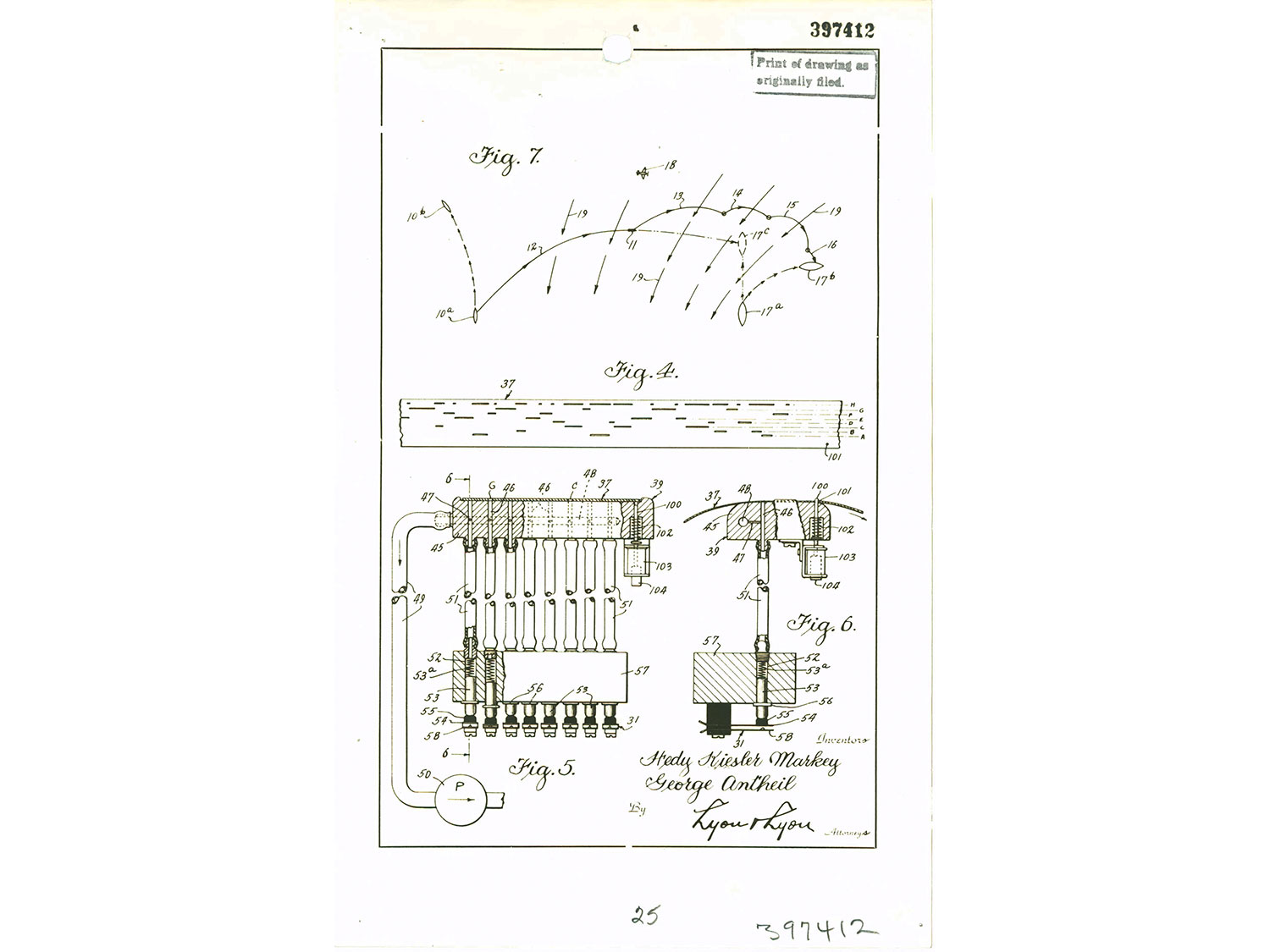

George was stuck making the daily trek to Beverly Hills, where he and Hedy would sketch out concepts for their frequency-hopping device in her living room. The crux of the design, it is thought, was inspired by player piano scrolls, which play tunes by interrupting sound in a pattern. In the case of frequency hopping, the pattern would be random. Antheil had experience with piano scrolls; he synchronized 16 of them to create his orchestral masterpiece called “Ballet Mécanique.” For their device, it would be more like 88 piano rolls working in tandem.

When Heddy and George thought they had it, they brought their concept drawings to the National Inventors Council. They were blown away. Believing it could actually work, American inventor and member of the council, Charles Kettering, connected the unlikely inventors to a physicist at Caltech, who designed the electronic device based on their concept drawings.

Photo Courtesy of National Archives at Kansas City, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Lamarr and Antheil were granted their patent, U.S. Patent Number 2,292,387 for their design, called the “Secret Communication System” in 1942, and they presented it to the U.S. Navy free of charge. The Navy took one look at Hedy and said, “Thank you,” and stuck it in a filing cabinet, but not before stamping it “Top Secret.”

And that was that. It was forgotten.

Hedy was told if she really wanted to help America win overseas, she should go out and kiss for war bonds. And though she wasn’t an American citizen, the Austrian native deeply loved this country, so she did. At the Hollywood Canteen set up to entertain the troops, she sold smooches, as well as autographs. Lamarr is credited with raising $25 million for America’s war effort, amounting to over $343 million today.

Many years later it was discovered, that in the mid-50s, the Navy had unearthed Lamarr’s patent, and shared it with a subcontractor to create sonobuoys, bobbing devices that could detect submarines below the water and transmit their locations to passing airplanes above. In 1962, the Navy adapted Lamarr’s technology during the Cuban Missile Crisis, and all of the U.S. ships sent to blockade the country were outfitted with frequency-hopping devices. A decade later, the devices were used in the surveillance drones that flew over Vietnam. Today, U.S. Milstar satellites, designed by Lockheed Martin, employ the technology in protecting the most sensitive military communications, including nuclear command and control messaging.

After the U.S. military released the patent, it became available to the private sector. That’s when the communications industry came across the patent and began applying frequency hopping, using digital signals instead of radio waves, first in GPS systems, and later in Wi-Fi and Bluetooth. Each requires a receiver to be able to hop from one digital signal to the other to create a seamless connection.

And though Hedy’s contribution was lost to time for decades, in 1997, she was honored by the Electronic Frontier Foundation, after one of its members discovered the patent and made the connection that the “Hedy Kiesler Markey,” to whom it was granted, was the legendary actress Hedy Lamarr. On all official documents for the patent, Lamarr used her second husband’s surname, Markey, because she thought it would be taken more seriously. Although Lamarr passed away in 2000, she was inducted posthumously into the National Inventors Hall of Fame in 2014 for the development of her frequency-hopping technology.

By 1997, when Lamarr was first recognized for her invention, she would not go out in public and sent her son to accept the award. During the acceptance speech he gave on his mother’s behalf, his cellphone rang. It was Hedy, so he answered it and put it on speakerphone for the crowd. She wanted to know how it went. Her son told her, “It’s still going, Mom. I’m kinda in the middle of it.” The crowd gave her a standing ovation. Privately, however, when Lamarr was told of the award, she quipped, “It’s about time.”