Originally produced in 1981 and a very famous flop, “Merrily We Roll Along” is now the biggest hit on Broadway and deservedly so.

Stephen Sondheim and George Furth had a major success with “Company,” a musical whose structure defied the traditional approach of a single plot line, instead telling the story of a commitment-phobic bachelor looking at the marriages of his friends, each in single vignettes disguised as scenes. A decade later they teamed up to make “Merrily We Roll Along,” based on a 1934 play by George S. Kaufman and Moss Hart. Following the structure of the source material, “Merrily We Roll Along” tracks a trio of friends in reverse with the end as the beginning and the beginning as the end. Pay attention. There will be a quiz.

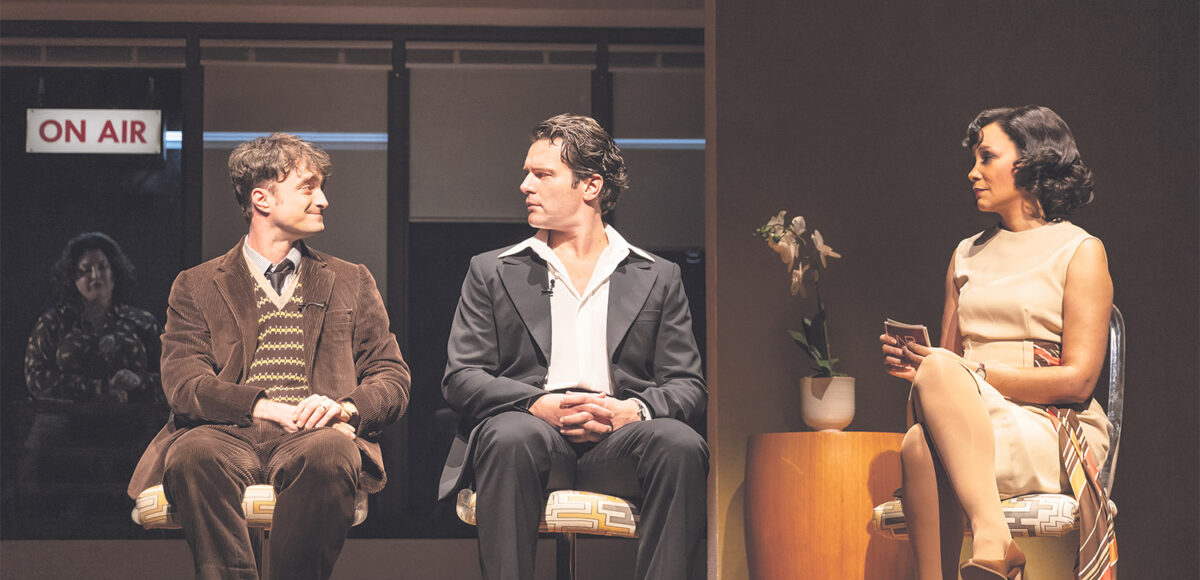

We meet Franklin Shepard, movie producer, as he hosts a party at his Bel Air estate for his friends honoring the success of his latest production. Alone in a room full of people, his celebratory motions are hollow as he flirts with his young star and ignores his bitter wife. He’s wooing wife number three as wife number two angrily looks on. He’s at the top of the heap and it is clear that he is cynical, dissatisfied, alone and lost. It is 1976, and someone has the nerve to bring up his former writing partner, Charley Kringas, recent recipient of the Pulitzer Prize. He, Charlie and Mary Flynn, were, at one point, an inseparable trio. Only the very cynical Mary, formerly a novelist and now a professional alcoholic, an unwelcome guest at the party and reminder of the past, still remains. Soon, as the various interchangeable members of the company sing “Merrily We Roll Along,” as ironic as it’s meant to be, we are transported back to 1973 as Charley and Frank are about to be interviewed on a popular morning show. The focus is on Frank, the more celebrated “face” of this musical writing duo as he talks of his, I mean their, work with false modesty. When, finally, Charley is asked about their collaboration, he lets Frank have it with both barrels of his frustration on national television. And that, ladies and gentlemen, is the explanation of why, three years in the future, Charley is not at the party as well as why he may have found the release to write the work he had always been trying to write.

Each successive, well actually backward glance is a puzzle piece that informs the previous scene, a major departure from traditional story structure where you see the actions that caused the consequence in linear form. Here, you first view the consequence and then the causation until, eventually, you arrive at the beginning that has been informed by the past rather than the opposite. You see his divorce before you see the why. All the “ah ha” moments are to come, until finally the puzzle is solved about who he was. It’s a very tricky structure and ultimately more satisfying than if we watched the consequences of actions unfold chronologically. This is not easy on an audience because “Attention must be paid!” The regrets of a lifetime are played out in reverse.

In many ways, this is the story of a Faust who succumbs to the temptations placed in front of him by Mephistopheles. Franklin is Faust who wants more than the treasures he already possesses. Mephistopheles is Gussie, wife number two who dangles sex and commercial success in front of him so tantalizingly that he is helpless, or perhaps too vain, to turn them down. Watch for all the incarnations of Gussie as she, herself, travels a devious and narcissistic path that you will also see in reverse, always hauntingly leering in the background of the three friends and Franklin’s wife Beth.

“Merrily We Roll Along” has had a checkered history. First produced in 1981 with a very young cast, a major blunder because it is the adults who drive the story, its muddled staging was more confusing than edifying. Always ascribing the difficulties to Furth’s book, many hopeful productions followed. I have loved this play since I saw a production in 1985 at the La Jolla Playhouse starring John Rubenstein, Chip Zein, Meredith McRae and Marin Mazzie, a dream cast to rival the present one. I never saw it as flawed or hard to follow. This should have been the indication that the right cast is imperative, something that other productions failed to see. But no one gave up on this musical and cuts were made to the script, tightening the story and finally in 2012 a new version premiered in London at the Menier Chocolate Factory, transferring to the London West End, which was a hit, critically and commercially. I saw the filmed version that was released, but unlike the National Theatre Live series, the magic didn’t translate. It took 10 years, but the London version made its way across the pond, first to the tiny New York Theater Workshop and finally to Broadway. It is nothing short of a triumph.

Photos courtesy of Matthew Murphy

In analyzing what I think were the major changes to the script, this new version focuses primarily on Franklin. In the past, more time was spent on the group as a trio, but though Charley is still enough of a major character to help drive the story even when he’s not there, Mary’s role has been diminished. That she has always loved Franklin and always been disappointed does not need a significant footprint in the story. One can easily surmise that her alcoholism, seen in full bloom at the party (again, the end of the story) is the result of crushed dreams and lost love, expositionally referred to by many other characters as in “Is Frank the only one who doesn’t see that she’s in love with him?” But this is something that actually adds depth because it is enough of a story point to highlight his narcissism and callous use of her. Beth, Franklin’s wife, is more present than I had remembered her. In so many ways she’s the angel on his shoulder that he chooses to brush off when someone dangles a shiny object in front of him. And again, you see the result of her disillusionment before you see the cause. Even more, however, is the character of Gussie, someone I did remember as wife number two but missed her presence in scenes that added to those that came before (or, rather, after but told before).

In short, the way that the story is told, starting out at the end, adds dramatic impact to the way it was at the beginning. It is nothing short of breathtaking.

Maria Friedman, who directed the Menier Chocolate Factory version, directs this production with the same clarity, intelligence and passion. Her staging is so remarkably simple that you never notice the set changes until you are midway in the scene. Lighting, a few pieces of furniture, a stairway and a piano are rearranged to represent a Bel Air mansion, a penthouse apartment, a downtown club and more. The ensemble singing “Merrily We Roll Along” introduces all the yearly transitions, beginning in 1976 and ending in 1957.

As was true in the 1985 version that I saw, this play is very cast dependent and Friedman’s cast is extraordinary. The evening I saw the play, the role of Mary Flynn, normally played by Lindsay Mendez, was played by Jamila Sabares-Klemm. She was wonderful, but a reminder that much of that role has now been reshaped and cut. Katie Rose Clarke plays Beth, Frank’s wife (seen first as they divorce). Krystal Joy Brown is Gussie, the gorgeous, seductive temptress who drives much of Frank’s story without us realizing it. It is only at the beginning (I mean the end) of the play that he is jaded enough to see it, but it will take all of the previous years to fill in that information for us. Hers is a sly, subversive portrayal where she and Frank get what they paid for.

Daniel Radcliff is a triumphant success as Charley, the partner left behind who wins in the end. He has a show-stopping number called “Franklin Shepard, Inc.” that will make you forget that he was ever Harry Potter. Like Neil Patrick Harris looking to distance himself from “Doogie Howser,” Radcliff has taken enormous care to build up a repertoire of Broadway roles that illustrate just how good an actor (and singer) he is.

This production of “Merrily We Roll Along” would not succeed without an actor willing to plumb the depths of unsympathetic narcissism and that actor is Jonathan Groff. With Groff, Friedman found an actor who could find the weaknesses and dark parts of this character. As the plot unspools in reverse, we see who he became before we see how he started, yielding maximum dramatic impact on what was lost. The song “Old Friends” takes on a different meaning as the years flash back. “Here’s to us. Who’s like us? Damn few.”

But there was always the music and it lived on regardless of some of the woe begotten productions. You may not even realize that “Our Time” — “It’s our time, breathe it in. Worlds to change and worlds to win” came from this. So did “Not a Day Goes by” — “Not a day goes by, not a blessed day. But you’re still somehow part of my life and you won’t go away.” (Bernadette Peters’ heartbreaking version can be found on YouTube.) All of the music is wonderful and with each reprise the songs take on a different meaning, something that is especially true for the title song “Merrily We Roll Along” that, depending on the time frame in which it’s sung, can be cynical or hopeful.

So, drop everything, get a ticket, hop on a plane and don’t miss “Merrily We Roll Along.” At present there are no plans to extend the run beyond March 24.

Now playing at the Hudson Theatre, 141 West 44th St., NY, NY

Editor’s Note: The Courier is proud to announce that our contributing entertainment editor Neely Swanson is a finalist in the the Los Angeles Press Club National Arts & Entertainment Journalism Awards. The presitigious awards are given to writers across the nation for journalistic excellence, career achievement and contributions to society. Neely is a finalist in the “Columnist” category, along with distinguished writers from the L.A. Times, Variety and Bloomberg News. We hope readers will join us in wishing Neely “good luck” at the awards ceremony, which takes place on Dec. 3 at the Millennium Biltmore Hotel.