This year’s submission to the Oscars by Germany is a thought-provoking film that sends prickles of discomfort up and down your spine as you recognize yourself, others and society in general at this progressive middle school. Director Ilker Çatak, writing with Johannes Duncker, lures you into what seems, at first, to be a benign story about honesty.

New, young and enthusiastic teacher Carla Nowak has been at the school a very short time but is already aware of the atmosphere of suspicion permeating the staff. Little, and not so little, things have been going missing at the school. Boxes of supplies, art materials and sundry other, seemingly unimportant but noticeable items have disappeared. Carla, knowing nothing of these illicit activities, does spot another teacher removing coins from the “honor box” by the coffee machine. The undercurrent in the teachers’ lounge is of dissatisfaction and mistrust led by two of the more senior teachers, Thomas Liebenwerda and Milosz Dudek, leaders in their own right (and maybe just in their own minds).

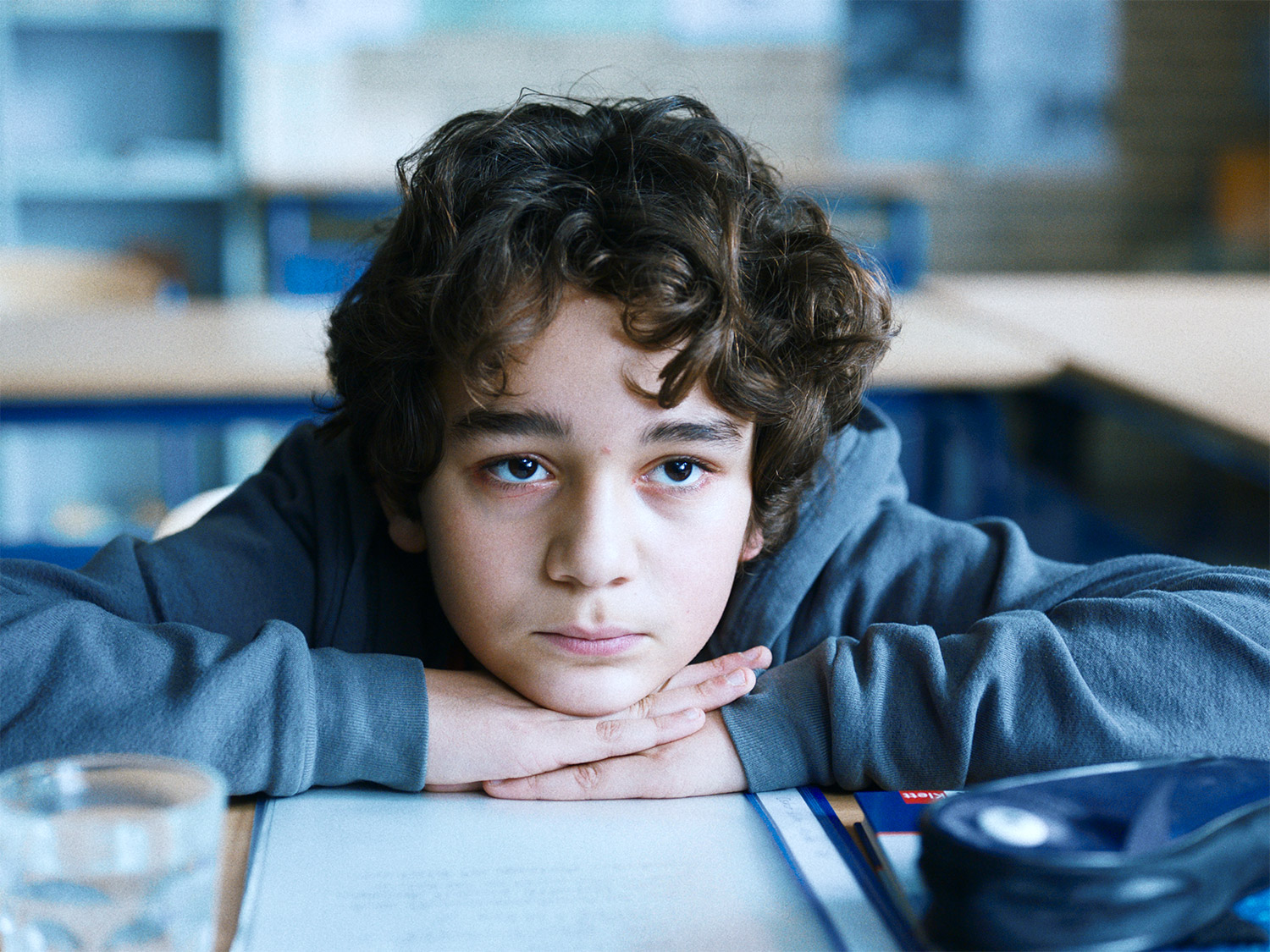

Carla has an easy rapport with her students. Respectful, she is even-handed and tries not to embarrass anyone in class who is struggling. That, however, all changes when those two senior teachers arrive at her classroom, asking to interview the two elected class representatives. The five of them go off privately, at which point Liebenwerda and Dudek begin to pressure the two students while a horrified Carla looks on. Money has gone missing and rumors are circulating that it is someone in their class. Before she can adequately get a handle on the tactics being used to bully the two students, the two senior teachers present a list of their classmates and ask them to single out anyone they think may be involved in the theft. Jenny states that she has no idea and wouldn’t want to guess. Lucas, however, succumbs to the coercion and, wanting to please, points to a name. He has pointed to the name of the Turkish student in class, Ali.

Photos by if Productions and Judith Kaufmann, courtesy of Sony Pictures Classics

Soon, the principal, Dr. Böhm appears in Carla’s class, accompanied by henchmen Liebenwerda and Dudek, requesting that all the girls leave and that the boys place their wallets on the counter. It is only Ali with a wallet full of cash. A pall hangs over the room as Ali is escorted out. His parents, called to the school to discuss the ramifications of their find, are perplexed. Immigrants, still uncertain of the language and customs, they endure the politically correct explanations of Dr. Böhm about their zero-tolerance policy on rule breaking. But, his mother explains, she had given him that money to buy a game after school. Oh. Sorry. Well, back to class you go. Except there’s no going back now that a cloud of guilt hangs over Ali’s head, and it’s Lucas, the so-called well-meaning collaborator, who’s happy to fan the flames of doubt. Relationships are bruised and the fabric of trust among the students and the teachers has been frayed.

Carla must attempt to repair the damage as each student looks suspiciously at the others. Camaraderie has decreased and the tolerance for mistakes and differences is lessened. When Carla catches one student cheating on a quiz, something he vehemently denies, her easy-going geniality is tested as she publicly singles out the alleged cheater. Safe zones no longer seem to exist and the students all feel like targets.

Carla, recognizing the rifts in her classroom, including the ones she has created, decides to take things in hand by investigating the thefts herself. Her method is ingenious but extra-legal and the result is shocking. But the repercussions are greater than she could ever have imagined as she is suddenly turned into a villain and not a hero. The parents, blaming Carla, rebel against what they see as totalitarian tactics; the children turn on one another; and the majority of the teachers reveal the smug attitude of the righteous. And in the center? Carla, who believed her intentions were impeccable and geared toward supporting the students. Instead, she has unleashed a tsunami of collateral damage, much of it aimed at Oskar, a sensitive and brilliant student she has been nurturing. Oskar has been caught in the crosshairs of defending his family and relying on a teacher who had supported his individuality.

In his own way, Çatak has created a microcosm of society in general. The unjust accusation of one student was the thread that, when pulled, unraveled the entire sweater. Carla, in her misguided way to try and right a wrong, has disturbed the universe and unleashed a force that destroyed the delicate framework of trust that everyone assumed had existed. Alliances are formed, enemies created and the children who had previously relied on the guidance of the adults around them are without the mature protection of those they counted on.

In “Lord of the Flies,” William Golding illustrated the disintegration of society with his tale of shipwrecked boys on an isolated island fending for themselves. Eventually, without the underlying structure of adult supervision, the boys on the island devolved into destructive predators attacking the weakest link. In “The Teachers’ Lounge,” the seemingly responsible adults acting in the so-called best interests of the students, have shredded the structural anatomy of their small society. With a zero-tolerance policy, there is no shade of gray, only black and white. Accusations become fact and the most vulnerable are left to make sense of the world that has been destroyed in front of them. Truths become lies; rumors become truth.

Çatak’s universe, placid on the surface, is, in reality, chaotic and easily broken down. The production design highlights the ultra-modern school as a beehive, the outside of which is dominated by the clean, efficient winding staircases used by the students to navigate their world; at the core is a messy colony where the teachers are seemingly in control. When the interior eats at the exterior, the entire mechanism collapses.

Çatak’s view of the world in general is complex, rather cynical and laced with humor. Much like a boa constrictor, he lulls you into a false sense of security until he gradually sucks the air out of your lungs. His masterful cast makes this all more than believable. Michael Klammer is the believably odious and self-righteous Thomas Liebenwerda. He’s so convincingly cynical and obtuse as the teacher who’s been at it far too long and feels ownership where it doesn’t exist. Anne-Kathrin Gummich uses her stiff as a board carriage to communicate her infallibility, which is anything but. She’s every principal you’ve ever loathed, while at the same time admiring her ability to keep a leaky ship afloat. Leonard Stettnisch in his debut as Oskar is achingly real. He shows vulnerability, hostility and confusion with one glance. That kind of communication in one so young is a rare find. What makes it more amazing is that he was recommended for the role by his father, Michael Klammer.

Leonie Benesch as Carla, is a true star, having already been recognized for her roles in Michael Haneke’s “The White Ribbon” and the television series “Babylon Berlin” (watch it on Netflix, it’s terrific). She brings the naive vulnerability that only a young idealist can hold. She wears all her emotions on her face and she grabs you and makes you ache for every mistake she makes, and there are a lot of them.

This will be an exceptionally competitive year for the Oscar in the International Film category, but this one should make the cut. It’s as chilling as it is heartbreaking.

In German with English subtitles.

The film is now playing at the Laemmle Royal.

Neely Swanson spent most of her professional career in the television industry, almost all of it working for David E. Kelley. In her last full-time position as Executive Vice President of Development, she reviewed writer submissions and targeted content for adaptation. As she has often said, she did book reports for a living. For several years she was a freelance writer for “Written By,” the magazine of the WGA West, and was adjunct faculty at USC in the writing division of the School of Cinematic Arts. Neely has been writing film and television reviews for the “Easy Reader” for more than 10 years. Her past reviews can be read on Rotten Tomatoes where she is a tomato-approved critic.