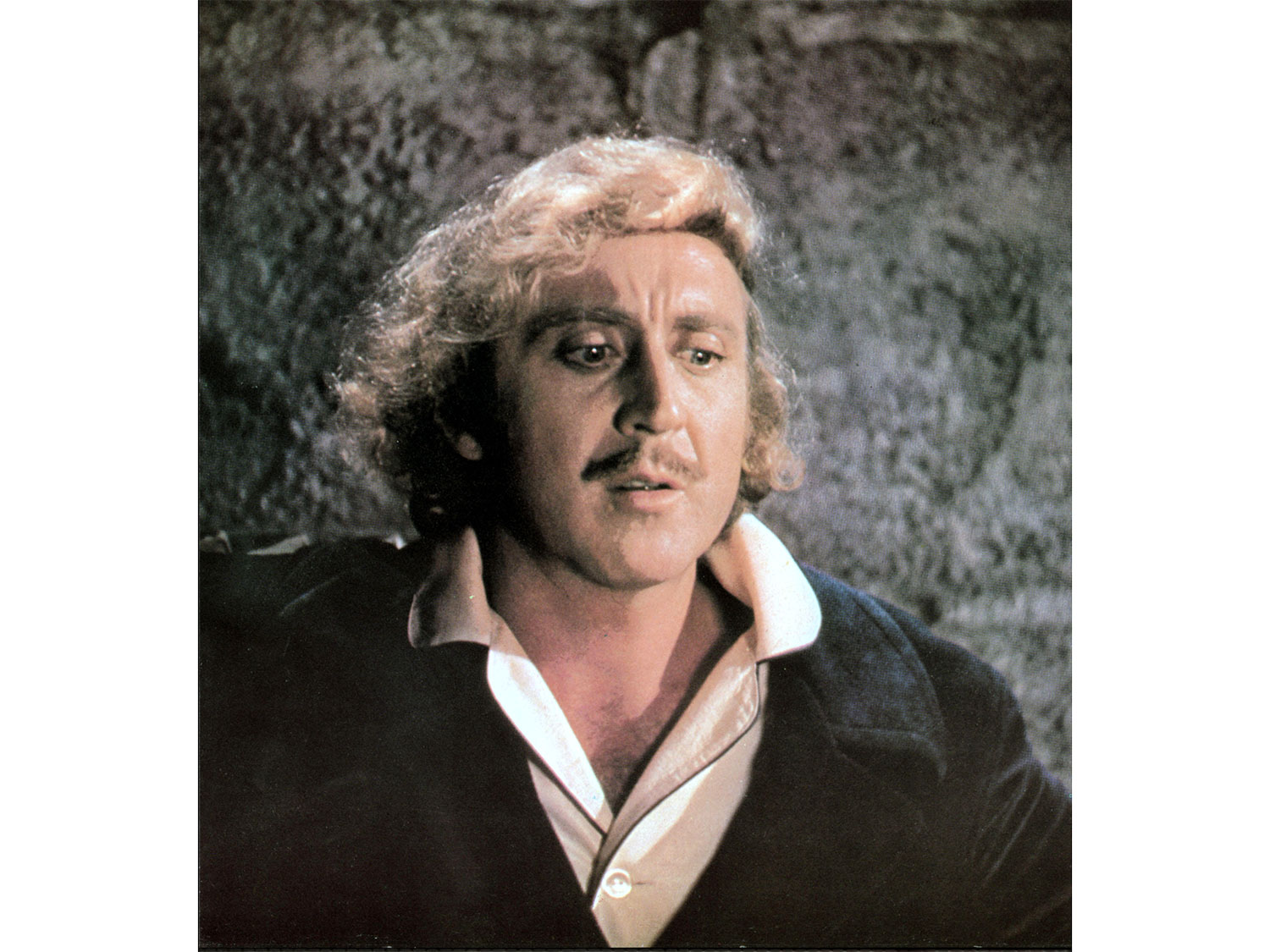

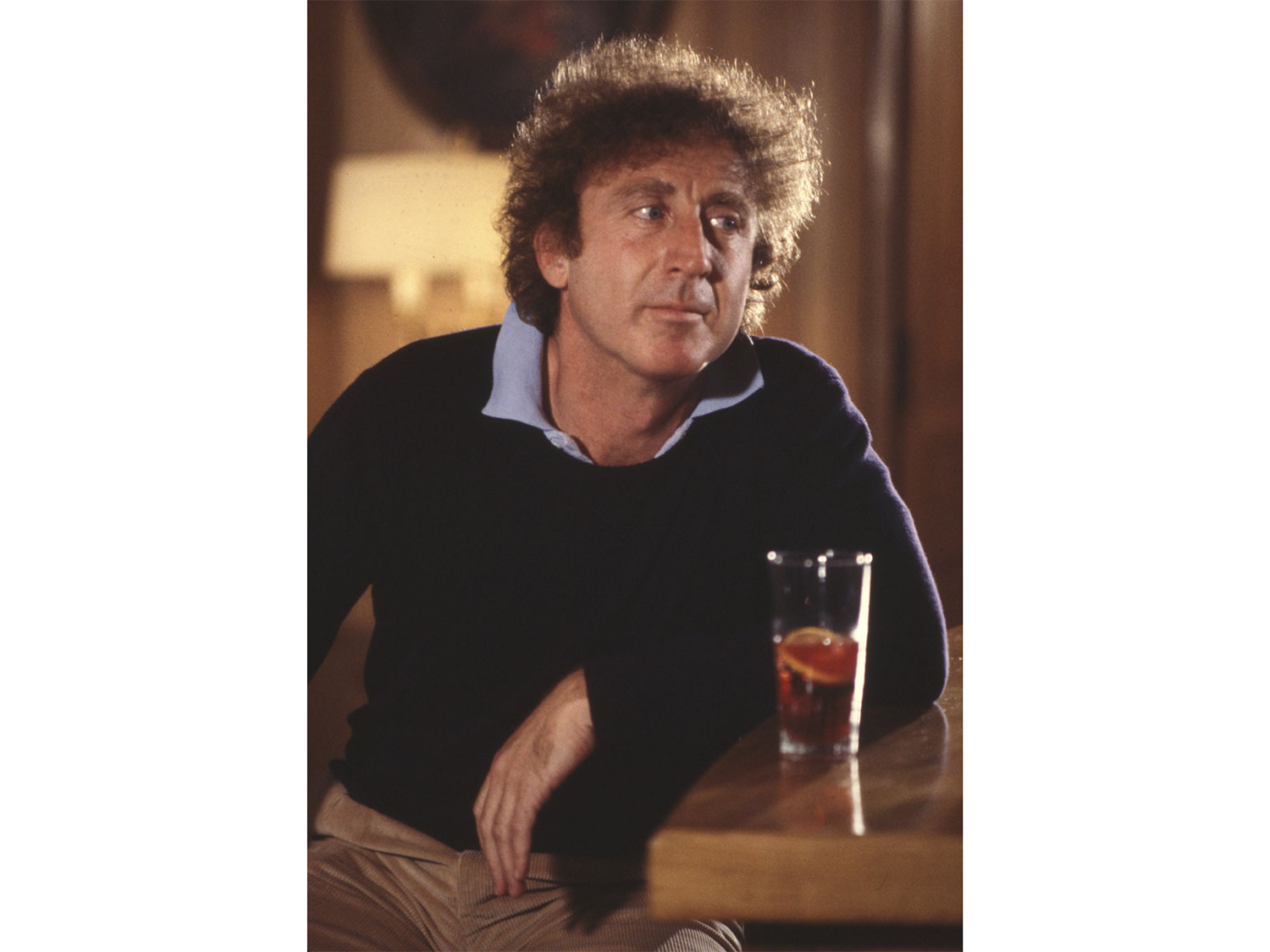

Celebrating an actor whose face could express infectious innocence as well as diabolical mischief, director Ron Frank and writer Glenn Kirschbaum have given us entree into the world of Gene Wilder by Gene Wilder himself, because it is his voice we hear throughout the film. Wilder’s self-narrated audiobook, “Kiss Me Like a Stranger: My Search for Love and Art,” is the base of the film, enhanced by archival interview footage and the recollections of friends, family and collaborators like Mel Brooks, Alan Alda, Carol Kane and Rain Pryor, daughter of Richard, next to Mel Brooks, one of Wilder’s most important film partners. And all of it is underscored by a treasure trove of clips from his many delightful films. This is Gene Wilder by Gene Wilder and what a warm and insightful story it is.

Raised in Milwaukee, this scrawny young man with the uncontrollable frizz on top realized that Jerome Silberman didn’t have much of a ring to it, so he rechristened himself Gene Wilder and, immediately after graduating college, struck out for New York, first finding small roles in television.

Kismet originally arrived in the shape of a small role, one where he felt very miscast, in a starry Broadway production of Bertolt Brecht’s “Mother Courage and Her Children,” a play that would close after 52 performances. But leading that cast was Anne Bancroft and she saw something in Wilder that she would pass on to her future husband, Mel Brooks. Brooks was writing his first film script, originally called “Springtime for Hitler,” and was agonizing over who he could find to play the neurotic accountant, Leo Bloom. The part, veering from naive innocence to deeply disturbed psychosis needed a believability factor that escaped most actors. He already knew who would play Max Bialystock, Zero Mostel, but who could possibly withstand the hurricane force of Mostel and still retain credibility? On Bancroft’s recommendation, Brooks came to see Wilder in the play and was instantly convinced.

Things move slowly in Hollywood and this was 1963, a full three years before there would be an actual production of what would become “The Producers.” Mel Brooks speaks extensively about what he saw in Wilder from the beginning and how Wilder understood the character of Bloom even better than he did. Watching some of his work in that film shows exactly why it was, as they say, a match made in heaven. But it wasn’t just Brooks who saw Wilder’s possibilities, it was also Zero Mostel, a famous problem child who had casting approval. He was in love with Wilder from the very first moment they read together and the rest is history. But the history has a few bumps in the road, including legendary Joseph E. Levine, the notorious vulgarian with impeccable taste in material. When shown dailies of Wilder’s work, Levine told Brooks to fire him. It wasn’t that Wilder wasn’t funny; he was. It was that he wasn’t handsome or a famous name. He insisted that a star was necessary. So Brooks did what he would subsequently do on all his other films. He promised to fire him and then ignored the command. Brooks and Bancroft added Wilder to their list of close family friends, something they would be forever after.

But before “The Producers” reached the screens he was seen in a movie that caught the zeitgeist of the time, “Bonnie and Clyde.” In the small role of an undertaker whose car is stolen by the famous duo, he made an indelible impression. Viewing a snippet of his performance underscores the statement by Arthur Penn, the director, when he admitted that he had never envisioned the role played the way Wilder played it and yet it was better, deeper and infused with humor that Penn hadn’t anticipated.

Wilder was on his way and when he was offered the role of Willy Wonka in “Willy Wonka & the Chocolate Factory” after a single line read, he happily jumped at it. Peter Ostrum, the boy chosen to play Charlie, recounts how incredibly helpful and generous Wilder was toward him, a true father figure. It was a surprising flop at the box office because parents were offended by its dark view. It has since become a cultural touchstone by the now grown children whose parents would not let them see it at the time.

Unafraid of a challenge, he next took a role in Woody Allen’s “Everything You Always Wanted to Know About Sex But Were Afraid to Ask.” For the chapter Allen had in mind, he needed an actor who could sell sincerity and believability in something that defied credulity. And that role was of a doctor who falls in love with a sheep. It’s hard to describe if you’ve never seen it, but I did see it and I still find it hard to describe. The one thing you can say about this incredibly tasteless vignette is that Wilder is totally believable and it still makes me smile to remember him in bed with that sheep. The combination of two box office flops didn’t do his career a lot of good until Kismet struck again.

Mel Brooks was just beginning production of “Blazing Saddles,” a comic western. The final piece to his casting puzzle was the all-important role of the Waco Kid, the drunk counterpoint to the Black Sheriff played by Cleavon Little. Gig Young, a veteran of stage and screen comedies and dramas, as well as a fair share of westerns, was a gamble. A renowned alcoholic who had been fired from many productions, Young and his agents swore he was two years sober and all his difficulties were behind him. Readying for his first scene, Young’s stomach and everything else seemed to explode and he had to be rushed to the hospital. He was still in the throes of his very active alcoholism and was suffering from DTs (delirium tremens). Asking the physician whether Young could return to work, he replied, “Yes. In three or four months.” Horrified, Brooks recalled that they were to begin formal production in three days and he was now without a co-lead. But Brooks had a go-to position and that was his good friend Gene Wilder. With no preparation, Wilder took the role of the Waco Kid and, once again, made the unbelievable believable and also incredibly funny. Their collaboration would continue with “Young Frankenstein,” based on an idea of Wilder’s with a script co-written with Brooks.

There are so many movies, some good, some not so good, but always inventive. His other enduring screen partnership was the one with Richard Pryor. Pryor’s daughter Rain comments on how important that screen partnership with Wilder was for her father’s career. On screen they had incredible chemistry and although this partnership did not translate to a friendship off screen it was a very important relationship for them both.

Frank and Kirschbaum are very inclusive when it comes to Wilder’s filmography but also in terms of his personal bonds, not just with Brooks and Pryor, but also with his two significant romantic relationships. Most famously, he was married to Gilda Radner. It was an interesting and volatile love affair that ended too soon when she died of ovarian cancer. His marriage to Karen Boyer was his enduring love; their meeting reflects the care and thoughtfulness he brought to all aspects of his life. While conducting research for the next movie he would write for himself and Richard Pryor, “See No Evil, Hear No Evil,” Wilder contacted the Braille Institute about how Pryor’s blind character would behave in various situations. He also sought out an expert on the hearing impaired for the character he would play. It was important to be funny but not offensive. That expert was Karen Boyer. Gradually their relationship became more than just professional and it grew into a deep and lasting love, one that lasted for the rest of Wilder’s life. There were many good times and they shared almost everything. Karen was with him when his memory started to fail and she was with him when he was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s. She was there for him until the very end as the two of them brought attention to this devastating disease that affects not just the patient but also friends and family.

I must confess that although I have appreciated Wilder’s acting in the past, I was missing a, rather the key element to all his performances whether in a good movie or a not so good one, of which he wrote many. As discussed with his friends, from Alan Alda to Brooks to several of his directors, he was believable even when the scene wasn’t. He was funny without going for the easy laugh. He was, in short, an actor’s actor and a mensch. Gene Wilder was unique and Frank and Kirschbaum lay that out loudly and clearly. That Karen Boyer Wilder gives us a very personal view of a man of depth and character is icing on a rich and nourishing cake.

Don’t miss this one.

Opening March 22 at the Laemmle Royal.

Neely Swanson spent most of her professional career in the television industry, almost all of it working for David E. Kelley. In her last full-time position as Executive Vice President of Development, she reviewed writer submissions and targeted content for adaptation. As she has often said, she did book reports for a living. For several years she was a freelance writer for “Written By,” the magazine of the WGA West, and was adjunct faculty at USC in the writing division of the School of Cinematic Arts. Neely has been writing film and television reviews for the “Easy Reader” for more than 10 years. Her past reviews can be read on Rotten Tomatoes where she is a tomato-approved critic.