When the United States government, for one brief moment in time, decided they would wield the sword of art and culture against Communism, they stirred up a hornet’s nest at the Venice Biennale. This is the story Amei Wallach tells in her fascinating documentary “Taking Venice.”

The Venice Biennale has been one of the most important art shows in the world featuring modern art. Winning the Grand Prize could be the launch of a new career or the underscore of an established one. Founded in 1895, it was suspended during the two world wars. Following World War II, it resumed in 1948.

The emphasis was supposed to be on contemporary art although one could argue that the winners from 1948 through 1956 were no longer on the cutting edge. George Braque, Henri Matisse, Raoul Dufy, Max Ernst and Jacques Villon were no longer part of the current avant-garde movement. Those wins did, however, serve to emphasize the preeminence of France as the center of the art world.

International in scope, exhibiting countries, most financially supported by their national governments, had longstanding invitations to build pavilions to exhibit their entries in a space allocated by the Biennale committee in the Giardini or in the park. The United States, barely an also ran, had a very small building representative of its minuscule offerings over the years. There was no government funding to support U.S. artists. But that changed dramatically in 1964 when the government, under the auspices of the USIA (United States Information Agency), decided that a strong American presence at the world’s most important art show could be used as a weapon in the Cold War.

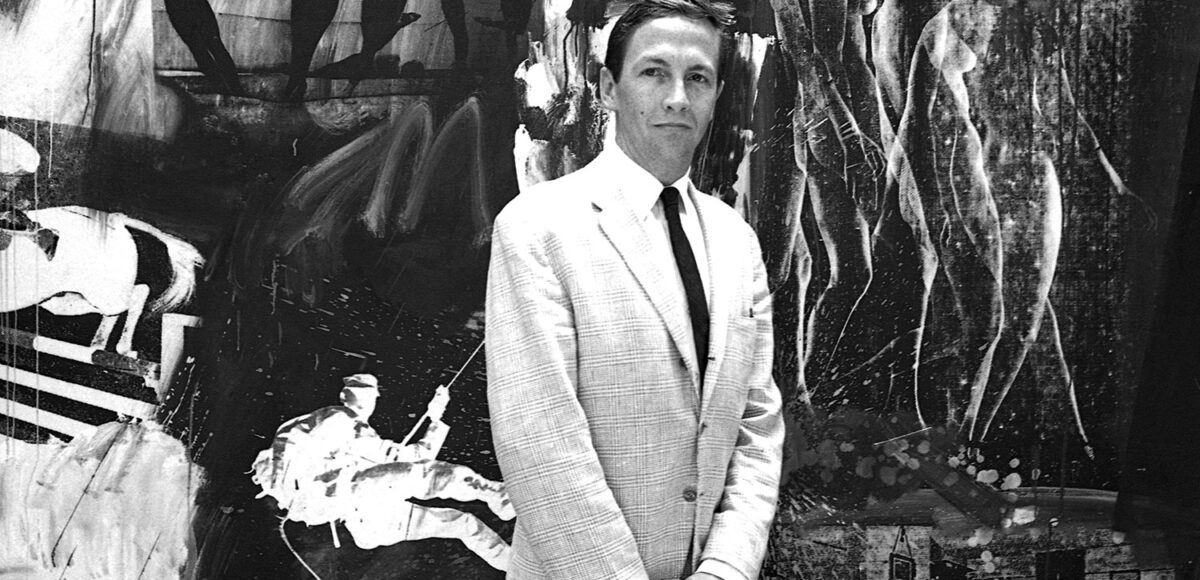

This is more than a movie about an international art competition; it is an investigation into longstanding rumors that the United States allegedly “fixed” the Biennale so their artist, Robert Rauschenberg, could win the Grand Prize. Despite the fact that there has never been any proof that there were payoffs or skullduggery, those rumors persisted. That Robert Rauschenberg was one of the leaders in the new contemporary art movement and more than worthy of recognition seemed to be beside the point. Other national governments supported their representatives, but the fact that, for the first time, the U.S. was providing financial support to a slate of artists entered as part of its delegation seemed to be suspicious. The who, the why and the how is the meat of this film and it’s a great history that is entrancing. It never once occurred to me that Rauschenberg should have been controversial. This was, after all, a competition in the arena of contemporary art, and by 1964 Rauschenberg was well established in New York circles.

Robert Rauschenberg caused an upheaval in the New York art scene almost from the time he arrived with his paintings full of “found objects,” silk-screened images and painted abstracts. Because he straddled the line between painting and sculpture, he coined the phrase “combine” to illustrate more clearly what he was doing with both media. An encounter at Black Mountain College in 1948 with the composer John Cage and Cage’s partner, Merce Cunningham, led to an artistic collaboration with Cunningham’s dance company. Rauschenberg would go on to create scenic and costume designs for the dancers, something that would influence the judges years later at the Biennale.

Rauschenberg would work with and have relationships with many of the emerging artists of the day, Cy Twombly and Jasper Johns, in particular. Their new art movement began slowly to gain traction as the Abstract Expressionists ceded precedence. But Rauschenberg refused to be categorized and critics had a difficult time placing him within a context. Nevertheless, by the end of the 1950s, he had arrived at an important juncture. He was represented by Leo Castelli, a gallerist who had become and would remain the leading purveyor of the new art forms. Not only did Castelli represent important Abstract Expressionists like Jackson Pollock, Willem de Kooning and Rauschenberg’s former partner Cy Twombly, but he also had literally everyone who was anyone in the new contemporary art movement including Jasper Johns, Donald Judd, Frank Stella, James Rosenquist and a whole roster of what would become the Pop Art movement, including Claes Oldenburg, Andy Warhol, Roy Lictenstein and Ed Ruscha.

Castelli, working with Alan Solomon, the progressive curator at the Jewish Museum in New York, determined that Rauschenberg deserved to win the Biennale, and be the first American to do so. (Technically he wasn’t because an American artist named Mark Tobey won in 1958.) Working with Washington insider Alice Denney whose husband worked for the USIA (but in a more nefarious branch), they set about getting the funding to take a show of the leading contemporary artists (not coincidentally represented by Castelli) to Venice. With Denney’s help, they did just that, enlisting Air Force transports and barges to transport these massively scaled paintings.

“Taking Venice” is remarkable not just for the story about Rauschenberg’s eventual win but also for all the background information on many of the players. Documentaries could be made just about Castelli and Solomon who shaped contemporary art forever. Alice Denney, now in her 90s, gives insight into the USIA sponsorship and the work that went into mounting the show. Archival and present-day footage show Castelli and his ex-wife Ileana Sonnabend reveling in the details of a politically rife journey. Sonnabend would go on to represent all the Castelli artists when she opened her own gallery in Paris. A more amicable divorced couple you will never find.

There were several factors fighting, in some cases battling hard, against the Americans. Lobbying for an American juror was treated as suspicious. Nevertheless, one was found who fit in seamlessly. But the real snag was the exhibition space. Because the American pavilion was so tiny, Denney, Castelli and Solomon requested that they be able to use the empty American Consulate building to show the works of the artists they had brought. The Biennale committee agreed to the use of the Consulate. Denney, on her way back home, reminded Solomon and Castelli to get that agreement in writing. They did not and when a new Biennale president arrived, he refused to honor the gentlemen’s agreement. This was but another obstacle for the Americans to overcome and Wallach does an excellent job of laying out the minefield that was still to be crossed.

After all these years, it’s difficult to fathom the extent of the controversy, so much of it political and not artistic. Although not internationally known at the time, the show set up at the Consulate exhibited not just Rauschenberg, but also Jasper Johns, Jim Dine, Claes Oldenburg, Frank Stella and John Chamberlain, all now household names and no longer of the avant-garde. How the American team overcame the interdiction of the American Consulate as a viable space is inventive and created yet more controversy. It’s no spoiler to reveal that Rauschenberg did, eventually after much ado (really about nothing), win. But it was a win that, for him, was tainted because it made him question his right to the prize. It was a monumental moment that seemed to be diminished to a footnote for him, much like the asterisk after Roger Maris’s home run record. Wallach gifts us with much footage, both archival and contemporary, of Rauschenberg both pre and post the Biennale.

You don’t have to love art to love this movie, although I do love both; but as a thriller with a known ending it also works on an entirely different level. The cast of characters are all interesting and the significance of the win turned the art world upside down, not because of who Rauschenberg was but because it spelled the end of Paris as the capital of the art world and marked the beginning of New York as that center. I’m sure the Parisians felt the same way the New Yorkers did when the center shifted to Los Angeles a few years ago.

How do you steal such a prize? Beats me. He didn’t, but it’s still a meaty discussion.

Opening May 24 at the Laemmle Royal.

Neely Swanson spent most of her professional career in the television industry, almost all of it working for David E. Kelley. In her last full-time position as Executive Vice President of Development, she reviewed writer submissions and targeted content for adaptation. As she has often said, she did book reports for a living. For several years she was a freelance writer for “Written By,” the magazine of the WGA West, and was adjunct faculty at USC in the writing division of the School of Cinematic Arts. Neely has been writing film and television reviews for the “Easy Reader” for more than 10 years. Her past reviews can be read on Rotten Tomatoes where she is a tomato-approved critic.