Tactics used by members of the Beverly Hills Police Department (BHPD) are under scrutiny following a viral video showing an officer playing copyrighted music while being filmed. The move seemed designed to trigger copyright filters used by social media companies to remove unlicensed material. In response to the video and subsequent media coverage, the department has opened a review into at least one of the instances.

Activist Sennet Devermont went to the Beverly Hills Police Department headquarters on Feb. 5 for help filing a public records request. Standing behind the desk was Sergeant William Fair. As Devermont frequently does, he streamed the exchange on his Instagram, which has over 300,000 followers.

“I wanted to do a public request for the body cam of a particular officer, I have the dates and times,” he tells Fair in the video.

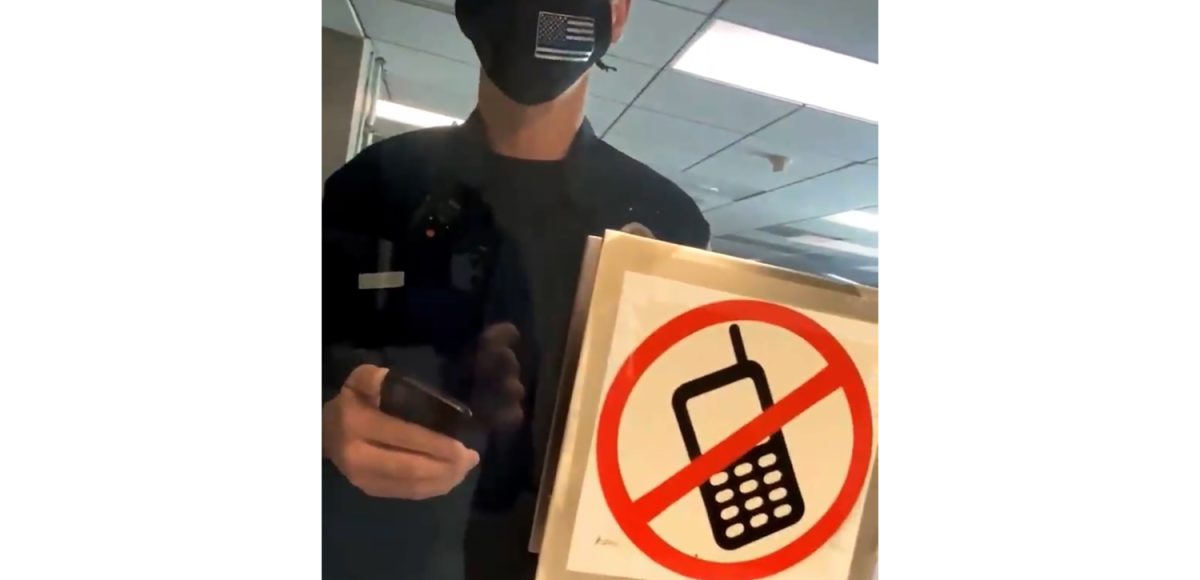

Fair asks Devermont how many viewers he has on his live stream. “Enough,” Devermont responds. Fair then reaches into a chest pocket and extracts his cell phone as Devermont asks for clarification on requesting public records. Then, music starts to play on Fair’s cellphone–the 1996 song “Santeria,” by the reggae ska band Sublime.

“Sir, you’re putting on music while I’m trying to talk to you,” Devermont says. “Can you turn that off?”

In an interview with the Courier, Devermont explained that he thought the move went beyond creating atmosphere. “I think they’re playing music that’s licensed and protected in an attempt to limit me from sharing and filming freely,” he said.

“The playing of music while accepting a complaint or answering questions is not a procedure that has been recommended by the Beverly Hills Police Department,” BHPD spokesperson Lt. Max Subin told the Courier. “This incident is currently under review by the Beverly Hills Police Department.”

Subin told the Courier that the department does not allow commercial filming in the building without prior authorization, but that Devermont’s filming does not fit that criteria. “[I]f you would like to film in the building for commercial purposes you need a permit from the City. The filming on a cell phone not for commercial purposes is understandable.”

Devermont posted the video to his Instagram, where it went viral and caught the attention of the news media. After getting a write up in the online publication Vice, the story went on to receive coverage by The Daily Mail, Newsweek, Los Angeles Magazine, Yahoo! News, KCBS, NBC LA, and KCAL.

The same pattern played out later the same day when Devermont encountered Sgt. Fair at the scene of a burglary on Palm Drive. Devermont again filmed the interaction.

“What are you doing by playing music?” Devermont asks.

“I can’t hear you,” Fair says, again playing music on his phone.

In an earlier instance on Jan. 16, Devermont filmed a conversation with Sgt. Fair when another officer nearby began to play “Yesterday,” by The Beatles.

“I just never know if I’m going to be that bad clip,” Fair tells Devermont. “When you catch somebody saying something that can be used and played over and over that just looks terrible when it’s taken out of context. It’s not really what they meant. I just don’t want that to be me.”

It is not clear whether playing restricted music in a livestream would automatically prompt the removal of the stream. In response to some confusion over its guidelines in May 2020, Instagram clarified its policy on including music in videos. “As part of our licensing agreements, there are limitations around the amount of recorded music that can be included in Live broadcasts or videos,” Instagram announced. The social media platform recommended that videos contain a visual component and that “recorded audio should not be the primary purpose of the video.”

Devermont says that even while Instagram has not removed the videos, it has still had a chilling effect on sharing them. In the case of the Jan. 16 clip, he says a news network could not play the video because of the music. He declined to name the outlet but quoted from an email sent to him by a producer. “Heads up, the story will not post online because of the music,” he read from the email. “Legal says we can’t play The Beatles.”

According to Lt. Subin, the department is also looking into the other instance of playing music while on camera.