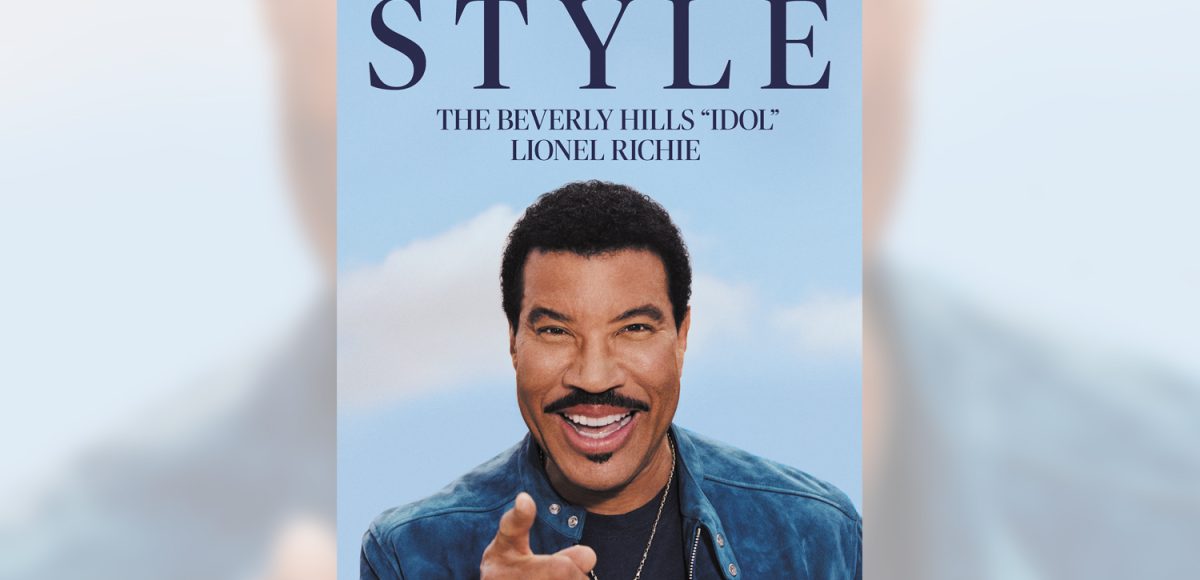

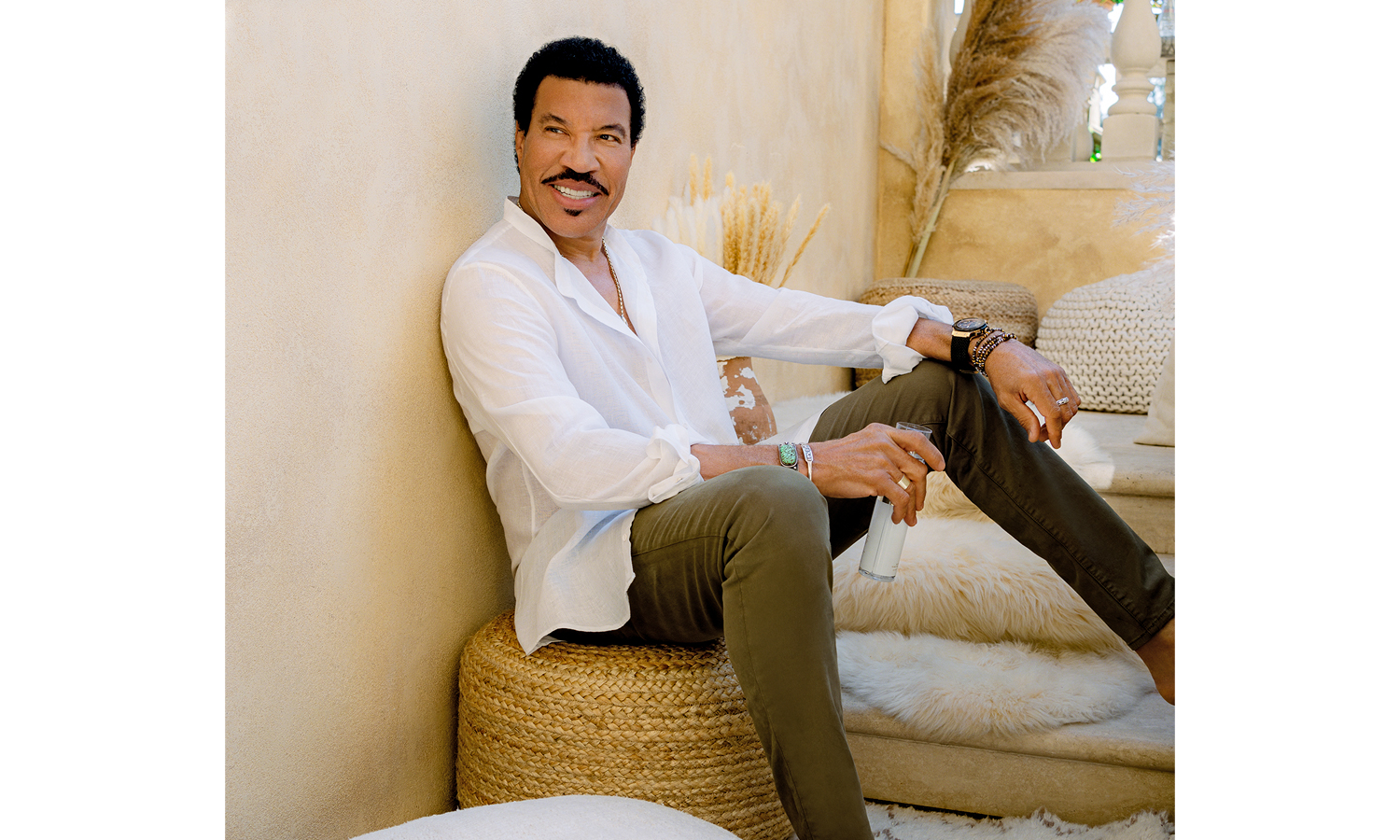

The Courier’s Lisa Bloch sat down with Lionel Richie to talk about his music, his passions and his life experiences.

Hello!? It’s Lionel I’m looking for Is that you?” The door to the trailer swung open and Lionel’s support staff, his stylist, hair and make-up artists, photographers, and assistants marched in, purposely focused, in anticipation of Lionel’s live national telecast of “American Idol.” Bruce Eskowitz, Lionel’s manager, who had been visiting with me, began to introduce me to Lionel’s team. And in that instant, the man I was looking for, the legendary Lionel Richie, walked in.

Brandishing his beautiful bright smile, Lionel held out his arms for my hug as Bruce quickly introduced me to him and his fiancé, Lisa. The interview had been set weeks ago, but something instantly told me my greeting was authentic Lionel. His warmth and charisma come naturally. As if we were friends from the neighborhood, the comfortable conversation began to gush. Or was it “me” gushing over him.

Lionel Brockman Richie, Jr. was born in Tuskegee, Alabama on June 20, 1949 to school teacher Alberta Foster Richie and retired army captain and Army System Analyst Lionel Brockman Richie Sr. Raised with his sister, Deborah, in the house across the street from Tuskegee University, music, religion, and academics were a big part of the Richie home. Lionel’s maternal grandmother, Adelaide M. Foster, a classically trained pianist and the choir director for Tuskegee University, sat regularly with Lionel at the piano, and encouraged him to attend the university’s musical events. His uncle, a big band player and arranger, stirred Lionel’s interests in jazz and provided Lionel with his first saxophone.

Once becoming a student at Tuskegee University, Lionel focused his energies, beyond his academics, on music. During his freshman year, he entered a talent show in a group called the Mystics. They had great success and were a big surprise to the upperclassmen. A well-known group made up of seniors, called the Jays, took notice. When they graduated, the two groups decided to merge. The Jays and Mystics became one, calling themselves the Commodores. In their travels they played a great deal of the venues referred to as the “chitlin circuit”.

In 1969, while Lionel was still in college, the Commodores traveled to New York for their first studio recording with Atlantic Records. While there, the group’s manager arranged for the Commodores to play at a black lawyers’ convention where Suzanne De Passe of Motown Records happened to be. Immediately impressed, she brought the group to Motown and signed them to open for the Jackson Five in venues and stadiums around the United States.

The Commodores’ first big hits, such as “Machine Gun” and “Brick House,” were known for their funky, danceable sound. Their first album debuted in 1974, the same year Lionel achieved his first success as a songwriter with “Happy People,” recorded by The Temptations. Lionel graduated Tuskegee University, that same year, with a Bachelor’s of Science in Economics. He married Brenda Harvey, his college sweetheart, the following year.

Thanks to Lionel’s song writing and lead vocals on love ballads, the Commodores amassed hits such as “Just to Be Close to You,” “Easy,” “Three Times a Lady,” “Still,” and “Sail on.” In 1980 Lionel wrote and produced “Lady” for country singer Kenny Rogers, and the title song for the film “Endless Love,” which was recorded with Diana Ross. It earned Lionel an Academy Award nomination, five Grammy nominations, an American Music Award and a People’s Choice Award.

In 1982, Lionel ended his association with the Commodores in a heartfelt break-up and released his first solo album, “Lionel Richie.” It sold more than two million copies, and featured the single “Truly.” His second album, “Can’t Slow Down” released in 1983 featured the “chart-popping” singles “Hello,” “Penny Lover,” “Stuck on You” and “All Night Long,” which he memorably sang at the closing ceremony of the XXIII Olympic Games. More success followed in 1986, with an Oscar win for his song “Say You, Say Me” for the film “White Knights,” and a nomination for “Miss Celie’s Blues” from the film “The Color Purple.” Another album followed that year, as did one of his most notable accomplishments. He co-wrote “We Are the World” with Michael Jackson. The single sold over 20 million copies, and the event Lionel mobilized raised more than $60 million for African famine relief.

In the late 1980’s, Lionel slowed down for a desperately needed break during difficult times. His father passed away, and Lionel’s marriage to Brenda (with whom he shared their adopted daughter, Nicole) ended. The “king of love” pushed forward. He married Diane Alexander two years later, and together they had two children, Miles Brockman and Sofia, who were raised in Beverly Hills. The couple divorced in 2004.

In the subsequent years, Lionel continued to write music, release albums and dazzle audiences globally. His tenth studio album, “Tuskegee,” in 2012, a compilation of 13 hit songs performed with country stars, brought him back to the top of the Billboard 200 chart. In 2015, his performance before 150,000 screaming fans at the Glastonbury Festival in England was hailed as “triumphant” by the BBC.

Accolades for Lionel have come outside the entertainment arena, as well. Three prestigious universities have awarded him with honorary Doctorates in music: Boston College, Tuskegee University and in 2017 the Berklee College of Music. He received the Kennedy Center Honors Award for his lifetime contributions to American culture in 2017. Lionel has been an advocate for Breast Cancer Research over the years. And in 2019, The Prince of Wales selected Lionel as the First Chairman of the Global Ambassador Group for the Prince’s Trust.

It’s no surprise that Lionel has said that he’s “addicted to exhaustion.” As a businessman, in 2018, while on “Idol,” he said “Hello” to home décor, launching his “home collection” business. He has invested in “Heal,” a service that provides home-based medical care. Lionel thinks of it as an “Uber doctor” in the privacy of one’s own home. And his perfumery business, aptly named “Hello,” uses his creative sensory talents. Lionel’s newly-released scent has been recognized as the 2020 Fragrance of the Year, top five finalist, by the Fragrance Foundation.

Success in these new endeavors is hardly surprising, given Lionel’s accomplishments thus far. He has won four Grammy awards as well as being named the 2016 MusiCares Person of the Year. He has one Academy Award, 17 American Music Awards, a Golden Globe Award, the 2014 BET Lifetime Achievement Award, and the NAACP Image Award for Entertainer of the Year. He is executive producing “The Sammy Davis Jr. Story” for Paramount Pictures as well as the Robert Johnson movie for the studio, and a film for Disney Pictures that will feature Lionel’s songs. He begins his fifth year-long residency in Las Vegas this fall, at The Wynn. He’s back in the recording studio and has just completed his fourth season as a judge on ABC’s “American Idol.” Lionel is one of the world’s best-selling artists of all time, having sold over 100 million records worldwide. As a global icon, he is truly beloved.

Lionel, what made you fall in love with Beverly Hills?

Well, I just realized over the years that when people would say, “where are you going on your vacation?” some people would reply, “I’m going to Greece,” or “I’m going to London,” or “I’m going to Tokyo,” or wherever they are going around the world. I discovered something about Beverly Hills; I don’t have to travel anywhere. Everyone is from everywhere here. It’s such a diverse place that if you want Greek food, we’ve got it. Italian food, we have it. We also have the greatest stores. And by the way, you will bump into everyone in the world at every restaurant in town. It’s the greatest place because it has a European vibe but in America. One corner has one vibe; another corner has another vibe. One house has one vibe; another house as another vibe. It’s a melting pot of the entire world, and it’s just the coolest place to live.

Growing up in Tuskegee, your grandmother played Bach throughout the house and spent hours with you at the piano. Can you tell the story of when she discovered you couldn’t read music?

The first part of my life, I was trying to read music the honest way the way my grandmother was taught. So, one day, she gave me an assignment in which she would play it for me once, then leave the room so that I could rehearse the piece. When she would walk back in, she would say, “All right, here we go. Let’s play it.” Well on this one particular day, I must tell you, I played the piece from beginning to end, flawlessly, but my grandmother looked at me and said, “You didn’t read the music.” And I said, “Grandma, I read the music.” She said, “You did not read the music.” I said, “Why don’t you think I read the music?” She said because I didn’t turn the page. It was at that point I realized I was not able to read the music. But I could copy whatever I heard.

When did you realize that playing music by ear was not going to be an impediment?

When I joined Motown, and believe it or not, I realized shortly after that some of the greatest writers in the world – Marvin Gaye, Smokey Robinson could not read music. Paul McCartney, Michael Jackson, Erroll Garner, the great jazz player wasn’t that good at reading music, but he could really play from his own head. Once I got my own permission from them, I was able to experiment. Yes, they could play the piano, but they couldn’t do all that orchestration. That’s when I realized, I can do this. And, of course, hallelujah! It worked.

You were raised in the Deep South during the 1950’s and 60’s where racism was rampant. When did you become aware of the oppression, injustice and inequality around you?

When I was growing up in the South in Tuskegee, Alabama, I was basically living on a college campus. As kids growing up, we called it the bubble because we didn’t really know what was going on outside of our bubble. It wasn’t until probably the March on Washington on Walter Cronkite in New York on TV when I realized it was happening in Montgomery, Alabama, 38 miles away from Tuskegee.

Your parents worked hard to shelter you from the brutal realities. Why?

I have to tell you, I now understand when the Klan was marching through Tuskegee, in my early years. My parents put us to bed early. So, we never knew that they were marching. Anything that happened in terms of racism, they kept it from us. For the longest time we couldn’t figure out why our parents were shielding us from this. As we got older, I asked my mom and dad why they kept us out of that. They said, “because we wanted you to grow up knowing there were no limitations. And if we told you what was happening, and what people thought of us, then it might limit your goals as to what you would pursue in your future.”

Today, 50 plus years later, what advice do you have for all of those out there who are facing obstacles?

The hardest person in the world to get to know is yourself. The hardest person in the world you have to trust is yourself. The hardest person you have to believe in is yourself. And the most important person to meet, if you meet no one else, is yourself. All the world needs is your special understanding and interpretation of you.

As a world-famous parent, which has its built-in challenges, you often look back to the lessons you learned from your parents. Your father’s advice and teachings made an indelible mark on your life. Can you share some of his words that still resonate with you today?

He would say to me, over and over again, “aptitude plus attitude determines altitude.” If you are just smart, and you have all the aptitude and nothing else, you go halfway. If you just have the greatest attitude in the world but no aptitude, you go halfway. But if you have both of them together, the sky’s the limit. If you have to have only one, having the right attitude will put you in a higher position because people will like to be around you so much.

Another one I kept asking my dad, “I don’t understand why you’re so happy. I’m playing back your life and you’ve had a very difficult life. I don’t understand why you’re just so happy every day?” And he said, “Son, if you lose your sense of humor, they have you.”

They have you?

You can lose your house; you can lose your money; you can lose friends and family. But if you lose your mind, it’s over. The only way to really survive in this world is to have a sense of humor. And I have found that over the years, that is the only thing that has gotten me through some very difficult times. In the face of complete disaster, I would think about how my dad would smile through this situation. And the answer is, it’s recoverable. If you understand that life is a challenge, life is painful, you can overcome obstacles. It was George Washington Carver who said, “Great men and women are not born. They were just individuals faced with a problem and overcame it.” I’m using that as my mantra as I go through life.

Community means everything to the City of Beverly Hills and to the Courier. Please tell us about the community in Tuskegee.

I refer to my growing up as the village. But really, it was a university campus where it was a melting pot. We had German professors, Czech professors, French professors, and it was just every imaginable kind of doctor and lawyer, etc. Segregation was all around us. Still, it was a melting pot. I use that association when thinking about Beverly Hills. In Beverly Hills, we have almost that same sense of community where we have just about every imaginable walk of life. It’s all religions and all cultures. It’s this incredible community of people. The world is in conflict, but we live in Beverly Hills where everyone is from wherever. You can actually come to Beverly Hills and get the best education of your life in terms of what the world is like.

The people in our community share a love for our city and enjoy its connectivity. My bet is you know your neighbors.

I do know my neighbors, and the people across the street. Especially during the pandemic, it’s become a really fun thing. I’ve gotten closer to my neighbors than I’ve ever gotten before because I’ve never been home for a year and four months. So, I mean, we’ve had all kinds of behind the mask kind of conversations, and I’ve gotten to know them even better. We have different views on things, but also, we have so much in common.

Who were your mentors? Who have you idol’-ized along the way?

Tuskegee, Alabama had some very famous people. I was very blessed. I didn’t realize that. Those guys walking around in those Airforce uniforms

those were the Tuskegee Airmen. As time went on, I realized, oh my God, Chief Anderson. Well, that was Charles Anderson’s father. He was the one who flew Eleanor Roosevelt in the first flight to see whether black pilots could actually fly a plane. She went up with Chief Anderson, Charles Anderson’s father. But he was Chief Anderson to us.

Even my grandmother and Mel Dawson, who wrote the Negro Symphony. He was just an amazing arranger, conductor, writer, and composer. He would come by the house talking about music with my grandmother. She also knew Booker T. Washington and George Washington Carver.

My family was a member of the Episcopal Church, and Father Vernon Jones had a huge influence on my life. He managed to get all of us to be interested in the lessons of the church by putting a ping pong table and a pool table in the undercroft of the church. Every Saturday we would go by the church, and he would teach us how to be altar boys and at the same time, we tried to beat him at ping pong and pool. It’s how he mentored us in terms of paying attention to certain things in life. I was very blessed.

And once you left Tuskegee?

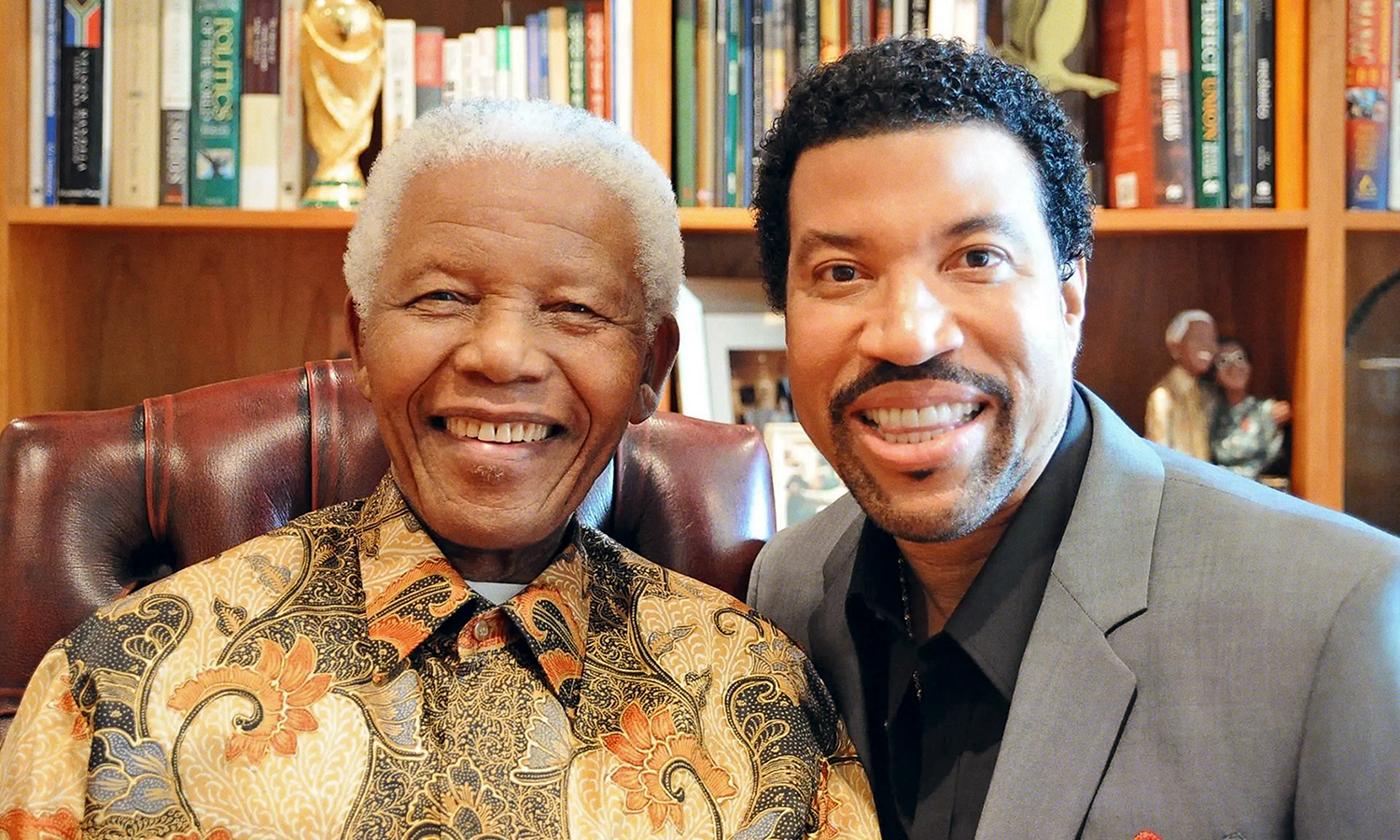

Outside of Tuskegee I must tell you, Quincy Jones, Sidney Poitier, and Gregory Peck [have been my mentors]. I happened to run into some wonderful, wonderful people when I first came to Beverly Hills, and they gave me solid advice on how to maneuver, and how to navigate the world of entertainment and the world of celebrity. Clarence Avant, Dick Clark, I can call off so many wonderful people. They were just there for me. And then of course, there’s a grandeur to have been able to have known Nelson Mandela.

Did you meet him in South Africa or in America?

I met him in America. When we first got word that he was coming to America, (a group of us) were all given assignments and it was funny – my assignment was to make sure that he had suits. So, I went shopping at Neiman Marcus with Winnie Mandela. I remember we were running around the store and this was the first time I ever met her. This sounds like a dream. But at the same time, it was such an amazing moment to know that this man just spent all this time in prison, and he came out, reunited with his family, and then came to L.A. and to New York for the first time. And we had something to do with it.

He whispered something in your ear that brought you to tears. What did that teach you about humanity and humility?

First I was in awe of being in his presence. It just fascinated me to know that a man can spend that much time in prison and come out and have his sense of humor and have the wherewithal to say that it was a teachable moment, instead of a bitter moment.

He whispered to me, “I want to thank you for your lyrics, because it got me through many years of isolation in prison.” The fact that he had heard my music, that he knew my music, and then for him to tell me that I contributed something to his health, mental health, whatever the case may be, just made me feel so worthy of being a human being and a songwriter. I was reduced to tears. I just didn’t realize I touched somebody so isolated from the world for so long.

On “Idol” you have said, “Singing is singing. Moving people to evoke an emotion is everything.” Did you make a conscious decision at one point that you were going to sing about love? Or did it naturally evolve from the hopeless romantic that you are?

Let me just establish the fact that I am a hopeless romantic. I am in love with love. There is nothing else that matters or survives. We come to this planet in search of love. We only feel good when we are loved, or we are in love with something or someone. It is just a natural thing of life. “I Love You” are the only three words that never go out of style. And so, it doesn’t matter whether you are a rock star, or a stoner or a gangster, or a politician, not to put that in the same light [laughs], but the point is sooner or later, you’re going to tell someone “I love you.” Three corny words. The simplicity of writing about things that matter, matters of the heart it’s timeless. I miss you; I want you; I need you. I’m lonely. I lost you. I want you forever. I always figured if I could get my music played at a wedding, I’m halfway there.

“Life begins after you step out of your comfort zone” is another one of your wise quotes, and one that truly resonates with me. Tell us about that shy young band member who was coerced to kiss a strange girl.

Well, I was unlike the guy you see and know now. I was painfully shy when I was younger, and I wanted desperately to be in this band, the Commodores. Everything was going along very well as the horn player, until I found out I was going to be a lead singer. I was writing the songs so I started spending more time up front as a lead singer. It was just Clyde, the drummer, and myself. The keyboard player was Milan Williams. I was the saxophone player. I prefer to say I was the best saxophone holder that ever lived.

When I got up to the front, remember very shy, I kept ignoring the girls. And so, members of the band kept screaming at me, “Kiss the girl in the front row!” And I kept saying, “I don’t know the girl in the front row.” Remember now, in Tuskegee, Alabama, you don’t just grab girls and kiss them. The guys in my band were older than me and had been in other bands before I’ve never been in a band before. So, I’m up front, and finally, I bend over and I kiss the girl in the front row. The entire room screamed. And then the next problem they had after that was “Lionel, stop kissing the girl in the front row and sing the song” [laughs].

What about the unexpected pairing of you and Kenny Rogers? You were a saxophonist in a funk band and a budding song writer, and he was a country singer? Your power ballad, “Lady” became a record-breaking hit for him. It also helped launch your solo career. Please tell us more about this “gruesome twosome” and about this lifelong friendship.

It was the most unlikely friendship, but now that I look back, probably the most divinely orchestrated brotherhood that could ever happen in life is the story of Kenny Rogers and Lionel Richie.

I got a phone call from Kenny saying, “I would like to have one of your ballots.” 21 million copies later, it was just the greatest thing that ever happened since sliced bread. From there, we became buddies. But he lived here and I lived in Alabama. He kept trying to convince me to move out here and I kept saying “No, I like living in Alabama.” So finally, I was in his guest house in the Knoll, (an iconic property in Beverly Hills) and I said “I’ll just stay in the guest house here in Beverly Hills.” I was as happy as can be paying little money and making a lot of money, and writing “Hello,” “All Night Long,” etc. That was a magical house. Then Kenny sold the house to Marvin Davis, after I was the one who showed Marvin the house because I was in the guest house working on the songs. So I made a deal with Marvin Davis, “I get to stay in the guest house; I come with the house.” That was our joke. Marvin bought the house and I stayed in the [guest] house until finally one day he said, “I think it’s time for you to buy your wife a house

I think you need to basically get out” [laughs].

Kenny and I, from that point on, became this gruesome twosome. I was there when his kids were born. He was a brother that I never had. Every kind of experience that I was about to go through in my life, he had been through the same thing. When I was leaving the Commodores, he left the group, The First Edition. Every time I would go through a certain period of my life, he would sit down and tell me that this is what it’s going to feel like, this is how you should deal with it, etc. He basically was a mentor through that whole period of my life. I must tell you, there has never been a person that was more suited for my Southern roots. He’s from Houston, Texas; I’m from Tuskegee, Alabama. And for some weird reason, I’m still going back to look at my family history, because I know we were related somewhere along the line. He was just the perfect friend and we had so many years of laughter to the point where, no matter where we were, I would walk on stage and we had the greatest impromptu show of life. I miss him to this day; I really do miss him.

The Commodores were described as the “Black Beatles” from Tuskegee, but eventually the family broke up. You have described it as a challenging period. How do you reflect on it now?

Well, you just touched on a lot of things. The Black Beatles, we didn’t give ourselves the name. We played a show in Germany and in that show was the likes of AC DC, Queen was closing, and the Commodores were the opening act. Now, of course, what the heck are we doing on this show? But anyway, it was a disastrous show and just before we went out on stage, we did an interview backstage. In the interview they said, “who are you guys?” and we said “we want to be the Black Beatles. We’re going to take over the world.” When the article came out it said, “Look out world, the Black Beatles are coming.” That’s the greatest thing you could ever write. We only had two hit records. So, it was just hilarious.

But the break-up was very difficult because everyone saw us as a group. These were brothers I never had. In fact, I was saying every day “Thank God for the Commodores because then there would be no Lionel Richie.” And that’s the truth, because they gave me the opportunity to sit in this little cocoon, and just take it all in and grow and discover. From that little quiet kid who was shy on that university campus in that first talent show together to then going to Madison Square Garden.

You took a break from the entertainment industry in the late 1980’s. What did you learn during that time off?

That break was not a break I was expecting. Truthfully, I didn’t take that break because I said I think I need to take a break. That break was like a divine guidance break.

My father called me on the phone and said, “I’m going for a doctor’s exam and I want you to come and go with me to check this out.” You know, my dad was a military guy; I never saw him sick a day in my life. So, for him to ask me to do this and to be with him, I thought, oh, this is pretty serious. From that moment, I found that it was a slippery slope.

And what I thought was going to be a short period of time for him to recover and to go back, it ended up being two and a half years to his death. And then from there, I didn’t want to start the album and miss that opportunity to be with him. During this period, I also went through a divorce and throat surgery and everything else. It was a terrible period of my life. But it was very interesting it gave me an opportunity to do something I’d never done before, which is stop and reflect. I look back on it now as probably the best thing that could have ever happened because if I had kept going at the speed I was going, I would have probably crashed and burned. There’s just no way to keep up that kind of pace and not hurt someone whether it be mentally, physically, or emotionally. Something was going to break.

But I got to learn from my parents a lot more. I found out that I had great friends not only in Beverly Hills and in Los Angeles, but also in Alabama, because everyone was reaching out. And so, it gave me a sense of community again. People that knew me in Beverly Hills, but I didn’t think they thought enough of me that we were friends

they came forward and helped me through a very, very painful period. And so, it was one of those moments that I look back on. Yes, it was not pleasant in terms of what I was going through, but yet,

I think it did a great deal to mold me into who I am today.

“We Are the World,” was one of your crowning achievements. You co-wrote the song for more than 40 of the biggest musical stars of the day for African Famine Relief. Please share the challenges leading up to this once in a lifetime accomplishment.

This question right here could probably take three volumes of books; I am going to try to consolidate it as best I can. This was a monumental task of really not knowing what we were biting off.

Harry Belafonte called on the phone and said, “we have a situation I go to Africa every year, and we have a crisis. We need a