The Los Angeles County Metropolitan Transportation Authority (Metro) will soon complete the first step of one of its most ambitious projects to date. On Feb. 11, Metro will close questions on the Sepulveda Transit Corridor Project and begin compiling answers as a part of the yearslong environmental review process. The project aims to connect the San Fernando Valley, the Westside, and Los Angeles International Airport.

“This is an effort to really move more people through the pass without moving more cars,” David Mieger, Executive Officer for Transit Corridor Planning at Los Angeles, said at a December scoping meeting.

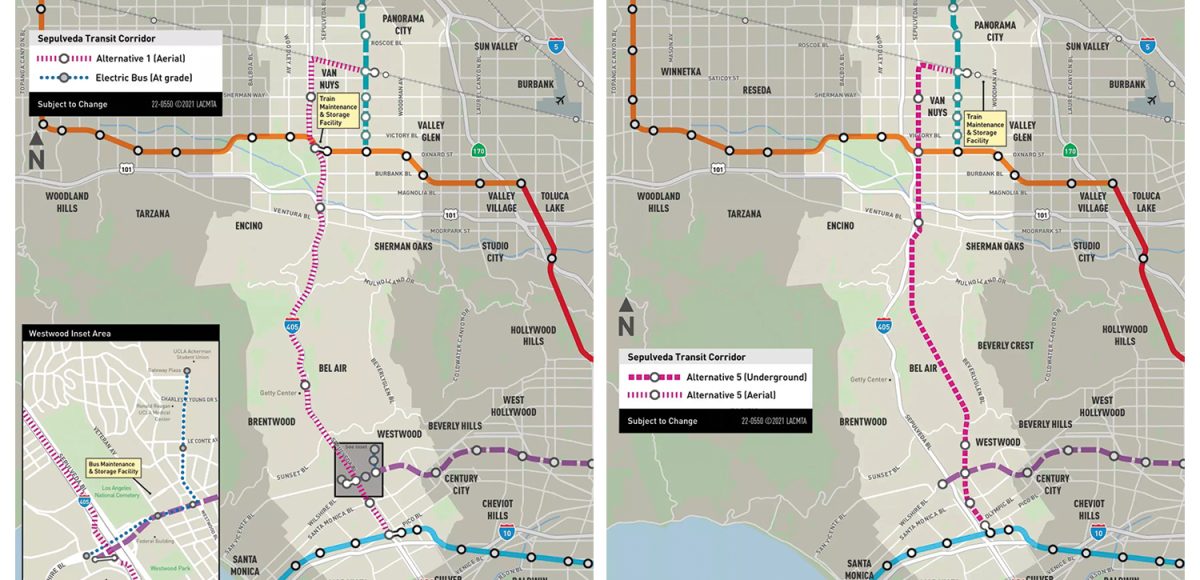

The project is split into two phases, with the first phase traversing the infamously congested Sepulveda Pass, home to the 405. Metro has proposed six possible alternatives for the project, which would all run between the E Line (formerly Expo Line) and the Van Nuys Metrolink Station.

Three of the plans propose the use of monorail, with the other three proposing heavy rail. The monorail options would run above ground in alignment with the 405. Two of the monorail alternatives would not include a UCLA station but would rely on either a bus or people mover to transport commuters, while the third alternative proposes tunneling under the campus to create a station.

The three heavy rail alternatives all incorporate a station at UCLA but vary in regard to how much of the track runs underground and above ground, in addition to whether the rail cars are automated, or driver operated.

February 11 marks the end of the public scoping phase of the environmental review process, a legally required and yearslong undertaking that results in an Environmental Impact Report (EIR). The EIR examines each proposed alternative for a project, analyzing the potential costs, benefits, impacts, and mitigations. The public scoping period gives anyone an opportunity to ask questions of the process and alternatives, which then get answered in the EIR.

Natural for a project of its scale, the Sepulveda Transit Corridor Project has generated both excitement and controversy for stakeholder communities on the Westside, in adjacent hillside communities, and in the Valley.

“People’s lives are really shaped by the lack of a public transit option between the Valley and the Westside,” said Andrew Lewis, who sits on the North Westwood Neighborhood Council, which includes UCLA, Westwood Village, and Persian Square. “This will really change lives in many ways.”

Lewis authored a motion in the Westside Regional Alliance of Councils, a consortium of 14 neighborhood councils on the Westside of Los Angeles, in favor of a station located on UCLA’s campus. The motion passed with support from 13 neighborhood councils, including Brentwood, Pacific Palisades, and South Robertson.

“Having a Metro Station located directly on the UCLA campus would also help transport the tens of thousands of individuals who travel to UCLA on a daily basis, including UCLA students, staff, faculty, medical personnel, patients, and campus visitors,” the motion reads.

“Not having a Metro Station on the UCLA Campus would be a sorely missed opportunity and have significant negative impacts on the West L.A. region and regional traffic congestion for decades to come.”

Only the Bel Air-Beverly Crest Neighborhood Council (BABCNC) did not vote in favor of the motion. In Metro’s preliminary plans, the inclusion of a UCLA station would require tunneling underneath Bel Air. In a letter submitted to Metro,BABCNCraisedconcernsaboutpotential noise and vibration effects from the project and requested that the EIR include analysis of potential wildfire hazards and seismic risks.

The nonprofit Bel-Air Association sounded an alarm in a recent email, warning homeowners that “[a] tunnel beneath Bel-Air will require Metro to obtain permanent easement acquisitions from Bel-Air homeowners, impacting rights to build on or improve one’s property.” The email said that the group would “do whatever is necessary” to oppose tunneling, including litigation.

In response to questions from the Courier, Metro Communications Director Dave Sotero said that if an underground route were chosen, the easements would be “hundreds of feet below ground” and unlikely to impact “residents’ future building plans.”

“However, Metro will assess easements on a case-by-case basis for each property owner in advance,” Sotero said. “We are required by law to provide just compensation to property owners for the purchase or use of their property to build Metro transit projects.”

On the Valley side of the project, the Sherman Oaks Homeowners Association (SOHA) has criticized all of the alternatives as flawed, in addition to taking aim at the process itself.

“I don’t understand why Metro does not want to share everything they know about the project and today’s six alternatives with the public,” Bob Anderson, SOHA board member and Transportation Committee Chair, told the Courier.

A letter submitted to metro by SOHA accused the agency of providing inadequate information on the alternatives during the scoping meetings.

Metro has said that the public will have multiple opportunities to provide input over the course of the environmental review process, including after the release of the Draft EIR.

Sotero said in response that the process can be “frustrating, as the alternatives do not yet have the level of specificity some local stakeholders would like.”

According to Metro’s current timeline, the first phase of the project will begin operations by 2033-2035.