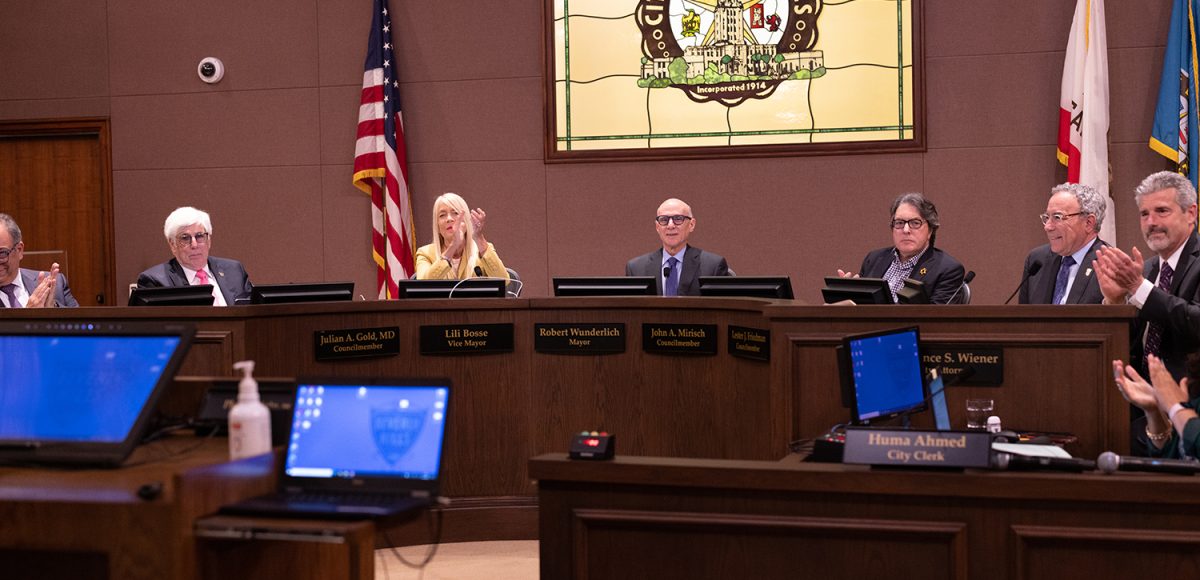

The Beverly Hills City Council met for its first in-person hearing in nearly nine months on March 15, giving the at-times grinding work of municipal governance an air of excitement and novelty. Utilizing a hybrid model where people could participate either in person or remotely, the Council heard an update on the city’s housing element and voted to reexamine the potential historic status of a sprawling home north of Santa Monica Boulevard.

The hearing began with an expression of solidarity with Ukraine as it continues to undergo a full-scale invasion by Russian forces. Mayor Robert Wunderlich, for whom this will be his first and last in-person hearing as Mayor, announced that the city would place banners in Ukrainian blue and yellow on the bridge that stretches across Rexford Drive to the east of City Hall.

City Attorney Lawrence Wiener updated the Council on the resolution passed on March 1 that instructed staff to research and identify possible Russian individuals and assets for potential sanctions. After a review of property records, contracts, and business licenses, the city had not found any sanctioned entities, but Weiner said that the city would continue to review records and would report back with any news.

The Council heard an update on the city’s general plan, a comprehensive framework for how the city will grow and develop its land. California requires that local governments submit an annual update on general plan progress.

As part of that review, the Council also looked at the status of its housing element, a comprehensive plan for how the city will accommodate growth over an eight year period that is included in the general plan. California just completed its last Housing Element cycle, which ran from 2014 to 2021, and began the most recent cycle in October 2021.

“We have a public hearing, so the public has the ability to see transparently what the city has accomplished and how they’re meeting their goals that are outlined in the general plan and housing element,” said City Planner Timothea Tway.

As part of the Housing Element, Sacramento tells cities how many housing units it needs to zone to keep pace with population trends. This number, the Regional Housing Needs Assessment (RHNA), has become a source of controversy, with local governments accusing the state of saddling them with an unreasonable zoning burden.

Among the state’s chief critics is Beverly Hills, which has a RHNA allocation of more than 3,000 units – an “unattainable” expectation, according to Councilmember Lester Friedman. For comparison, in the last housing element cycle, the city only had to zone for three units. Last year, the city saw the addition of only 17 units to the housing pool, all in the form of accessory dwelling units.

“We are being set up to fail,” said Councilmember John Mirisch.

Sacramento declined to certify the city’s housing element for this cycle, writing that “additional revisions are necessary to fully comply with State Housing Element Law.” Tway told the Council that she knows of only two jurisdictions that had their housing elements approved.

City staff will have a new revised draft complete within the next few months, said Tway.

The Council then turned to the historic status of 1001 North Roxbury Drive; a nearly 10,000-square-foot home located north of Santa Monica whose owner has asked the city to declare in writing that the property does not qualify as a local landmark. While the city initially granted the homeowner a certificate of ineligibility, Mirisch called the decision up for review.

“Quite frankly, when I saw this was issued a certificate of ineligibility, I thought why do we even have a Historic Preservation Ordinance,” Mirisch said. “Experts are sometimes wrong.”

The property was built in 1942 for Mildred Naylor by Beverly Hills master architect Carleton Burgess in the Regency Revival style. While the property retains its original core features and feeling, Director of Community Development Ryan Gohlich, who issued the certificate, found that it did not “satisfy the definition of an ‘exceptional work’ by the Master Architect as it was not the subject of any publications or architectural awards discussing or honoring the property for its design and merit.”

A certificate of ineligibility prevents the Cultural Heritage Commission or the City Council from designating a property as a landmark for seven years. This provides homeowners a level of reassurance to move ahead with changes to the property that would be barred were it deemed historic.

To receive a certificate of ineligibility, a property owner must submit a report by a historic consultant representing that the property fails to satisfy the criteria for landmark status set out in the Historic Preservation Ordinance. That report goes through a peer review process by the city’s own historic consultant.

The results of that peer review get circulated to the Cultural Heritage Commission before Gohlich makes a final determination. The City Council can call up the decision within a 30-day period.

“The staff memorandum, the applicant’s consultant’s assessment, and the peer review by the City’s consultant all concluded that the residence on North Roxbury Drive did not meet the criteria for local historic designation,” according to a report compiled by staff.

But in an eleventh hour-move, Cultural Heritage Commissioner Jill Collins presented the Council with two magazine articles written about the property. The discovery of the articles, she said, showed that the property might qualify as an exceptional work, as defined by the Historical Preservation Ordinance.

Cultural Heritage Commission Chair Craig Corman also addressed the Council, stressing that staff’s finding of ineligibility hinged on the lack of publications. “That was the sole basis on which staff issued a Certificate of Ineligibility and we now understand, having done some additional research over the last 48 hours, that was incorrect,” he said.

But Gohlich explained that the municipal code specifies publications “by people who have expertise in the field of architecture” and defended his determination, saying that the publications found by Collins were “somewhat obscure” upon first glance.

He went on to acknowledge that he did not have the publications brought by Collins at the time of his review. If he had determined that they fit the qualifications of the city code, “I would have referred it to the Cultural Heritage Commission for review,” he said.

Representatives of the applicant urged the Council not to review the determination.

“Everybody arrived at the same conclusion: this is not a historic asset,” said George Mihlsten, a representative of the applicant. “We respectfully ask that you not take this matter up.”

While the applicant’s team had not reviewed the articles at the time of the hearing, project consultant Harvey Englander argued to the Courier that at least one of the articles does not satisfy the city’s standards.

“There’s one article in Luxe Magazine, which is a very slick design magazine that solicits stories about projects. The author of the story is unknown, so there’s no way to determine if it is someone who knows anything about architecture,” Englander said. “The story itself isn’t about the architecture or the architect, it is about the interior design.”

The other article, according to Collins, appears in a foreign language edition of Architectural Digest.

While some council members expressed skepticism at whether the articles would sway the final determination, they felt their existence alone should prompt renewed scrutiny. The Council voted unanimously to call up the matter at the April 12 meeting.