Great architects speak in terms of alchemy, of animating the inanimate. And so it was with Shohei Shigematsu of the acclaimed Office for Metropolitan Architecture (OMA). Speaking to the Courier in January, he described a recently completed work in Los Angeles that “emanates vitality,” “shows respect” and on at least two of its remarkable sides, even bows.

The work in question is the Audrey Irmas Pavilion at Wilshire Boulevard Temple. The three-story, 55,000 square-foot event space is the new, provocative focal point of the Temple’s Erika J. Glazer Family Campus in Wilshire Center/Koreatown.

Completed in late 2021, the nearly $95 million-dollar structure is the first cultural commission in Los Angeles by OMA. It is also the crowning achievement of Senior Rabbi Steve Leder’s multi-phase “Building Lives” capital improvement campaign.

The pavilion itself is named for lead donor Audrey Irmas, a long-time congregant whose $30 million gift infused the first life into the project.

Philanthropist Wallis Annenberg also donated $15 million towards the building’s completion, as well as a separate $3 million to fund a Wallis Annenberg Legacy Foundation initiative for older adults. The result, Wallis Annenberg GenSpace, is housed on the pavilion’s third floor.

The late Eli Broad played a crucial role as well in the building’s genesis. The question of which architect to select came up in 2015 and Leder sought Broad’s advice.

“He told me to go after the best in the world,” Leder recounted during a private tour of the pavilion he led for the Courier late last year.

“I said, ‘Eli, do you really think the world’s top architects would be interested in this? And his response was, ‘This Temple, on Wilshire Boulevard, in Los Angeles? Of course, they will want to do it.'”

A competition ensued, during which a 15-person panel reviewed proposals from 25 architecture firms. Eventually, those 25 were narrowed down to four finalists.

Broad donated $100,000 to each of the finalists, enabling them to complete their submissions.

That OMA emerged the victor of the process was a bit surprising at first. OMA’s founder, Pritzker Prize-winning Dutch architect and urbanist Rem Koolhaas, has been an industry lightning rod for decades. He is known for works across the globe that are controversial, yet ahead of their time.

His recent projects of note include the block-long, “fishnet-draped” Seattle Central Library and the distinctive China Central Television (CCTV) headquarters in Beijing. The CCTV headquarters was cited by no less than President Xi Jinping in a declaration that no more “weird buildings” should be constructed in China. The New York Times, on the other hand, opined that the building “may be the greatest work of architecture built in this century.”

Koolhaas, it turns out, was only minimally involved in the pavilion after the initial design proposal. He later contributed the design for the mezuzot. Shigematsu, as OMA’s Partner-in-Charge for North America, helmed the project. His insights, perspective and affinity for Los Angeles (it shares an ocean and resulting light with his native Japan) are embedded in the pavilion’s backstory.

Large-scale inaugural festivities for the pavilion were postponed in January, due to the omicron surge. A smaller series of congregant open houses will instead take place in May, June and July. That is perhaps for the best. The pavilion should be appreciated at one’s own pace.

Events, including several b’nai mitzvah, have begun, with the new facility “eliciting awe” from those who come to the campus, according to Kimberly Supple, the Temple’s Director of Events and Operations.

In a January piece, The New York Times described the newly finished pavilion as “warm and vibrant.” Other media reviews have not been as positive. The Los Angeles Times, for example, wrote that the building’s elements were a “jumble” in need of editing, and proclaimed it “hard to love.”

That doesn’t seem what the structure is asking for.

Located adjacent to the Temple’s historic sanctuary, the Audrey Irmas Pavilion is at once overtly futuristic while at the same time exuding an ancient, even sacred, quality. It’s as if an oversized Ark of the Covenant – with all its power, mystery and magic – landed in the middle of Koreatown.

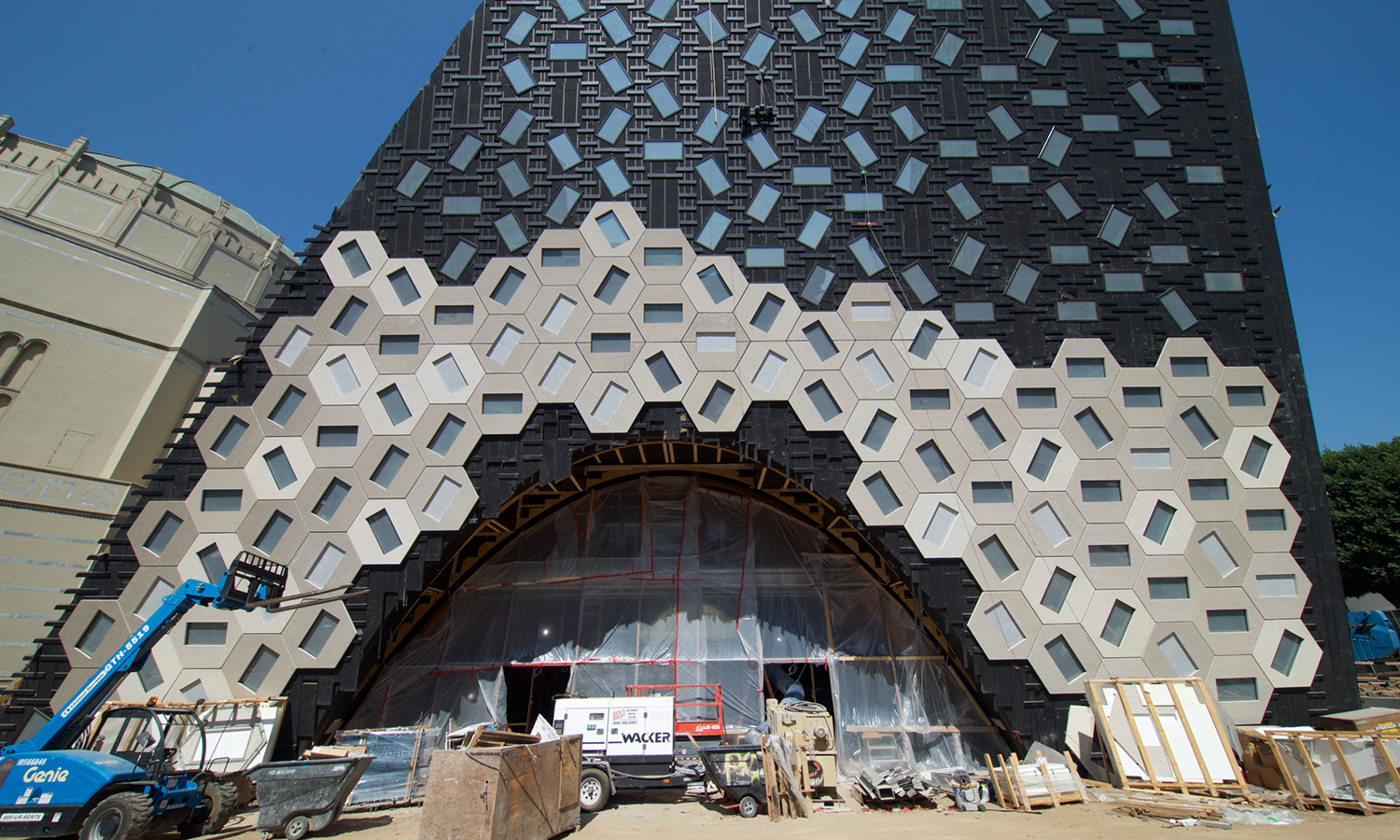

From a distance, the pavilion’s most notable feature is its rhomboid shape. Tiles cling to its exterior like the heat shields of the Space Shuttle. More than 1,200 tiles, in fact, constructed of glass fiber reinforced concrete. Their hexagonal shape mirrors the tiles of the sanctuary dome, bringing the inside to the outside.

Positioned at different angles, the tiles gleam in an array of hues. But that is an optical illusion.

“All the tiles are the same color,” said Leder, as he led us into the structure. “It just depends on how the light reflects on them.” The changing exterior hue was not planned by the architects, nor was the “confetti” effect caused by the rectangular panes of glass embedded within each of the tiles. At certain times of day, the glass reflects dappled dots of light on the exterior of the Temple and the interior of the pavilion.

Those are a few of the building’s unexpected surprises. But it was on the practical that Leder focused his enthusiasm during the tour. From its first planning stages, to fundraising and construction, the pavilion has encompassed nearly a decade of Leder’s 34-year tenure at the Temple.

Without question, the new pavilion fulfills the stated goal of providing much-needed event space for the oldest and largest congregation in Los Angeles. Its diverse array of venues can accommodate gatherings and ceremonies of every size and type, a point of obvious pride for Leder.

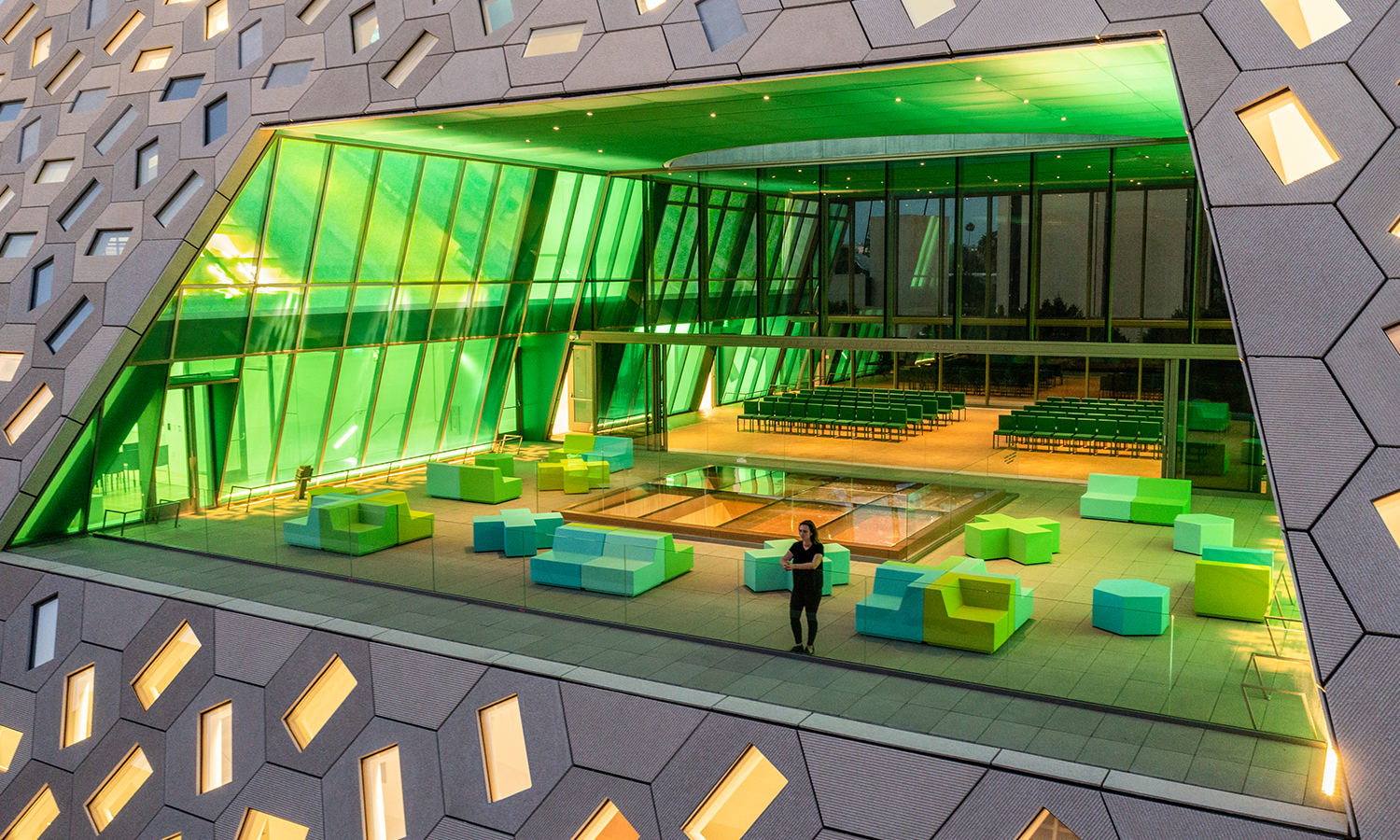

On the ground floor, a main ballroom covered in rust-colored wood spans nearly 14,000 square feet, all without visible support. The shape of its vaulted ceiling pays homage to the sanctuary’s magnificent dome. A second floor indoor/outdoor chapel space of emerald green glass can be configured for small ceremonies, while an intimate, ocean-blue sunken garden leads to an expansive rooftop terrace with dazzling panoramic views.

At one point on the second floor, Leder pointed out a window to the surrounding neighborhood.

“I think this will make everything else look better,” he said, as a modest concession to what will now join the ranks of the most significant buildings in Los Angeles.

Indeed, the pavilion’s uniqueness is not reserved for its exterior. Its interior is not built out in the traditional sense. It is more akin to a series of openings punched through the structure’s volume, creating light-filled spaces on, between and outside its different levels.

It’s all part of a vision Shigematsu was more than happy to describe for the Courier in a Zoom call from Tokyo.

He began by pointing out the challenge of designing a new building next to a historic religious structure.

“The synagogue is a very symmetrical building, a very monumental building, and a very serene building. What we wanted is a dialogue between that and an asymmetrical, lively and not particularly serene building; a building that wants to emanate vitality. So that is the dialogue, dignity and vitality,” he explained.

Though not constructed as a religious building per se, the pavilion shows an overall “clarity that could speak to religiousness or some kind of profoundness, which of course is important for religious institutions,” said Shigematsu.

He emphasized the desire to show deference to the pavilion’s setting.

“Typically, respect is considered maybe as an architect being polite. And some architects might think it’s a compromise to be respectful to the historic structure. But here, we thought that we could make a generic box more exciting by kind of blatantly showing the move of respect,” said Shigematsu.

That “move of respect” is a literal one, evidenced by the structure’s pronounced tilt. The building is inclined away from the Temple and toward Wilshire Boulevard.

“We made an inclination at an angle away from the Temple to provide a courtyard between the sanctuary and the entrance to the pavilion. We mirrored that inclination toward the Wilshire side to make a parallelogram. We thought we needed a dynamic presence on Wilshire, since it is one of the most important thoroughfares in LA.

“These two moves actually made the form quite complicated,” he added, in a clear understatement.

Security issues provided additional concern.

“We knew that we couldn’t have an entrance from the street, since that compromises security issues. So, the real entrance faces the Temple across an outdoor plaza. But we also didn’t want the building to look like a fortress because it was meant to be a beacon of openness to the neighborhood and openness to the rest of LA. So, what we decided is a more strategic porosity or contextual transparency.”

That “porosity” is effectuated in the three main event spaces, which Shigematsu likens to portals. He describes the main event space on the ground floor as a “corridor” that cuts through from Wilshire Boulevard to the campus’ Siegel Courtyard. The massive window overlooking Wilshire and the large skylight opening up to the second floor are further signs of the structure’s openness.

The trapezoidal, brilliant green second floor represents a “porosity in a different direction,” said Shigematsu. Whereas the ground floor connects Wilshire Boulevard and the courtyard in a north-south axis, the second-floor flows in an east west direction. Its signature feature is a huge covered exterior event space that looks onto the stained-glass windows of the Temple.

“At night, they are lighting the stained-glass window from the back, so you can see the strong relationship between the new and the old. Typically, you enjoy a church from the inside, but here you can also have a different vantage point to the exterior, which is rare, so I would say it’s an interesting relationship,” said Shigematsu.

The third floor is home to offices and activity areas designed for the Annenberg GenSpace. After conducting online programming for nearly a year, the space officially opens its doors on April 21 for classes, partnerships and events designed to enrich older adults.

The facility’s presence brings a synergy that pleases Shigematsu.

“The premise was that they were inspired by this architecture and then came to the space. The notion of aging and a religious institution is a co-relationship, I think. So, it’s an interesting hybrid,” he said.

Shigematsu added, “It’s great that an institution is always there. It is quite nice that there is some level of presence and activity always, not simply limited to an event. The problem with this kind of gathering building is when there is no meeting it could look dead or underutilized.”

It is doubtful that the pavilion will suffer from under-utilization. Bookings are quite robust for 2022. And Shigematsu is confident that the pavilion fulfills its mission as a desirable gathering place.

“I’m not saying that our building is acting like a church, but at least there’s a level of diversity and energy that makes people inspired to gather and meet again. In a way, the pandemic will hopefully highlight the importance of this building even more. We hope that this building’s energy and kind of shared diversity and character will at least inspire some people to come here and talk to people.”

He is also quite willing to share credit for the finished product.

“This is not our achievement only, obviously. People who really cared about having a great space, great architecture, great art and cultural continuity made this building happen,” he said.

He made mention of Broad.

“I always thought Eli had a profound drive to contribute to the culture of LA in art but also in architecture,” said Shigematsu.

He referred to Broad’s role in other high-profile bids in Los Angeles for which OMA was a major contender but did not ultimately receive the commission.

“Of course, there is some history but, in the end, we of course highly appreciate that he even held the competition for this building. If there was no Eli, I don’t think this building would have gone into an international competition.”

Shigematsu elaborated on what he meant by the term “cultural continuity,” and how it is reflected by pavilion.

“I heard that because of this building some parents decided to send their children to the Temple school. Those kids looking at this building will have slightly more familiarity with this kind of building. That will probably create another level of philanthropy in the future toward the cultural contribution of LA. So, I really love the fact that the building is contributing to the succession of culture in LA. Architecture sometimes has that kind of power.”

Without question, great architecture has that kind of power. And so do great Rabbis.