What a concept – a film about writing, a writer, and an editor told in an intelligent and compelling manner, using a visual medium to make it all jump off the page, so to speak.

Lizzie Gottlieb’s lifespan follows the same trajectory as the relationship between her father, Robert Gottlieb, and Robert Caro, the writer he edited. Born in 1971, it would have been just after her father began editing “Power Broker,” the biography of Robert Moses that put Caro on the map. A noted documentarian, she saw a movie in their acclaimed collaboration and, to quote a famous musical, she wanted to be in the room where it happened while they worked on Caro’s finale, the fifth and final book in his monumental series on Lyndon Baines Johnson, the 36th President of the United States. Little did she reckon with the strict parameters they set up. She could interview them; she could talk to them and others about their collaboration; she could do almost anything she liked in researching her story. What she couldn’t do was watch them work together or invade their process. Little did they reckon with her persistence, although her father should have known.

Lizzie may have been denied access to the “room where it happens,” but both men were very forthcoming on their relationship – the ups, the downs, the fights, and the genuine affection. It is, after all, a collaboration of 50 years, but one that isn’t as long as their respective marriages.

Gottlieb, the older, married his second wife, Maria Tucci, in 1969. Tucci, a well-respected New York actress, maintained a healthy distance from her husband’s work as she continued her independent career and helped raise their children. He was already a celebrated editor by that time, having started as an assistant at Simon and Schuster and ascending rapidly to become the editor and chief, later moving to Alfred A. Knopf, where he became president of the company. But there was always room in his day for Caro, even when he left Knopf to become editor-in-chief of the New Yorker.

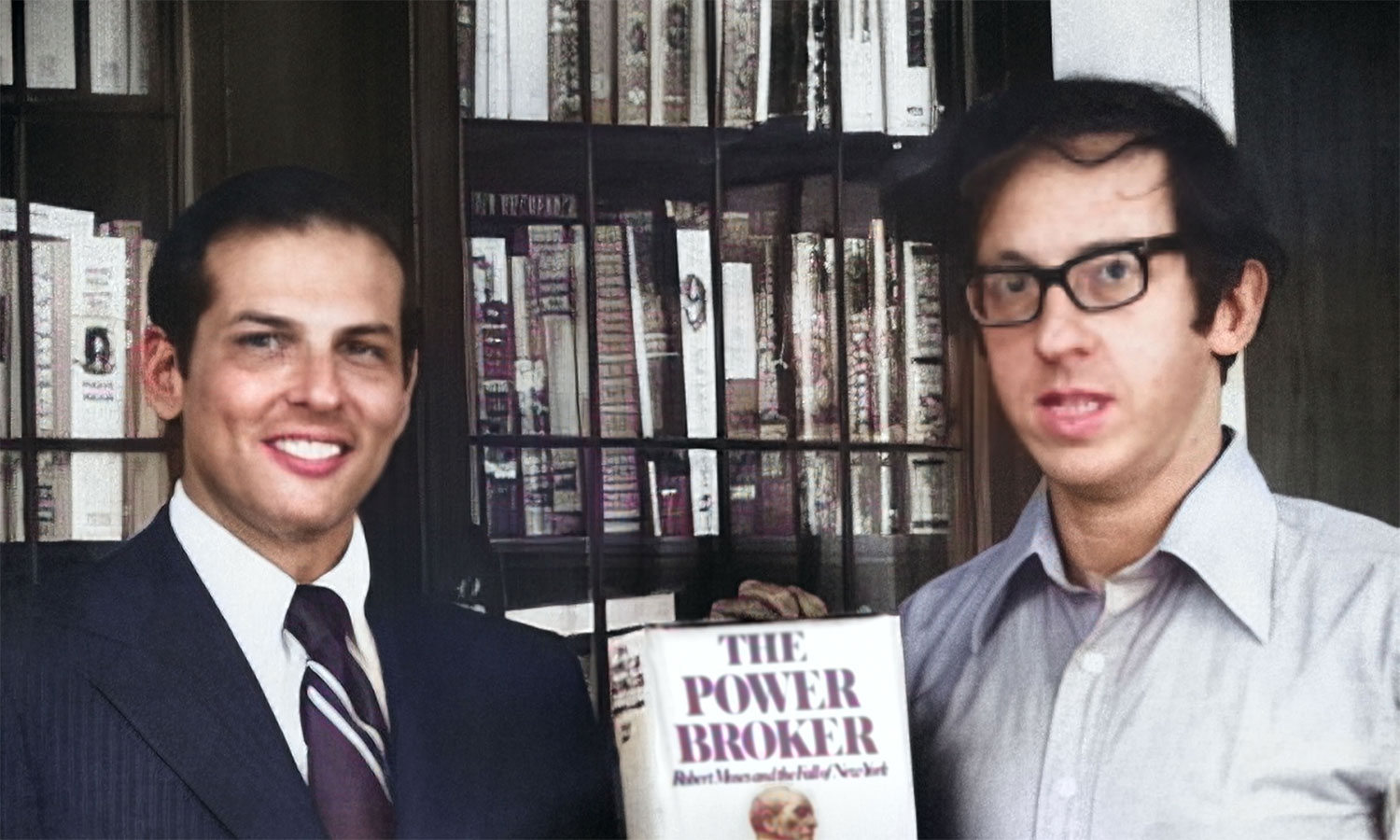

Caro married his wife Ina in 1957 and they have worked together ever since. Ina, a writer herself, is the only person he trusts as a researcher. Starting out as a journalist, he became obsessed with the “master builder,” Robert Moses, when he realized that Moses had more power in New York than any elected official. It was from that realization that he knew he needed to write the book that became “The Power Broker,” which took seven years to finish. It was Ina who supported his vision and managed to keep them afloat even while facing the harsh reality that there was probably a very limited market for such a book. This changed, both financially and psychologically, when he found a literary agent, Lynn Nesbit. Nesbit was enthusiastic about Caro’s possibilities from the moment she read part of his manuscript. She not only found him the money to finish the book but, more importantly, she found him the editor who would work with him throughout his professional career, Robert Gottlieb. Gottlieb, already the president and editor-in-chief of Knopf Books, knew it would be a masterpiece after reading only 15 pages of what would become “The Power Broker.”

Robert Gottlieb is now 91 years old; Robert Caro is 87. At this stage in their lives, that four-year difference is significant. Caro has been working on the fifth volume of the Lyndon Johnson saga for several years, but he’s not done and, as you can see, they’re not getting any younger. For both men, this is a race to the finish, or as Gottlieb calls it, an actuarial issue. He’s hoping they will both make it to the end.

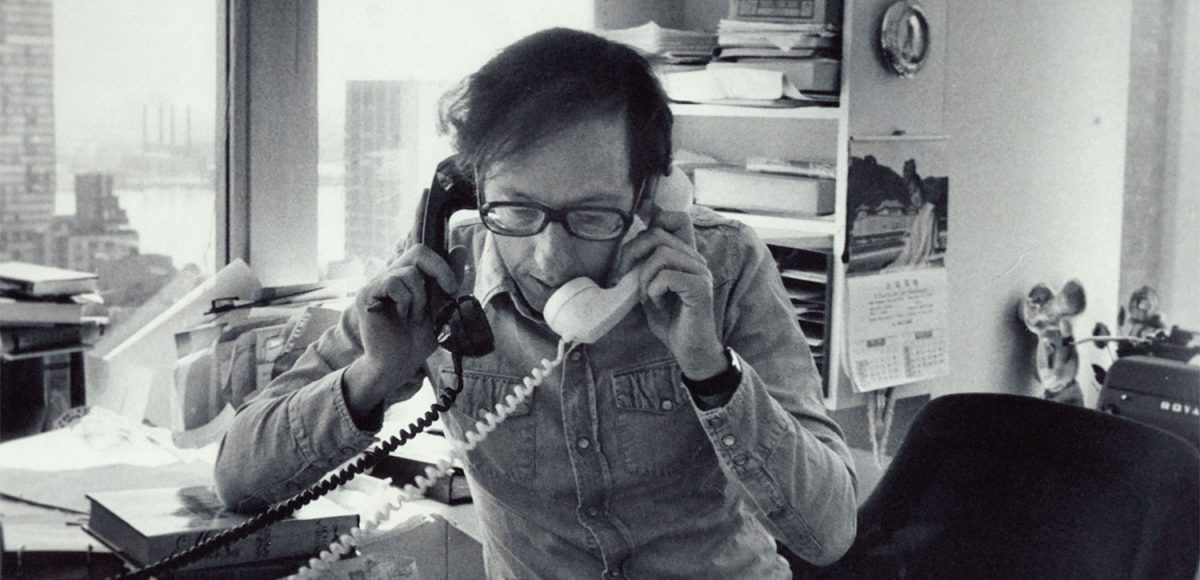

Lizzie got around their ban by interviewing them separately. Caro still writes his drafts longhand and then types the manuscript on his Smith Corona electric, with a self-adopted two finger approach, using carbon paper to make a copy of the work. For anyone under the age of 35, this will be an alien concept. There are those writers who still produce a first draft by hand. David E. Kelley is a classic example. But an electric typewriter is a device more familiar to visitors at the Smithsonian. And carbon paper? Go ask your parents or grandparents.

The thread running through all of Caro’s work, whether Moses or Johnson, is the dissection of political power and its effect on his subject, on society, on history. Who wants it, who gets it, how do they acquire it and how do you keep it? His greatest early lesson in the investigative process came from his managing editor at Newsday, Alan Hathaway. Explaining how investigative journalism worked, Hathaway told him, “Just remember one thing. Turn every page. Never assume anything.”

Gottlieb has been inextricably associated with publishing since the 1950s, in his own way taking up the mantle left by Maxwell Perkins, renowned editor of Hemingway, Fitzgerald, Thomas Wolfe, and others at Scribner and Sons. Perusing the shelves at the Strand Bookstore, a New York institution, Gottlieb points to a copy of “Catch-22” and informs his grandson that he was the one who came up with the number 22. It was originally Catch 18, but someone else at the time was about to publish a war book with “18” in the title and Gottlieb suggested to Joseph Heller that “22” was an even funnier number. The list of his authors is a compendium of some of the most famous literary figures of the later 20th century including Doris Lessing, Toni Morrison, Salman Rushdie, John le Carré, Ray Bradbury, Bill Clinton and so many others. Some of the books that passed through his hands during his early years were “True Grit,” “Something Wicked This Way Comes,” “Midnight Cowboy,” “The Chosen” and “The Andromeda Strain.”

There is a famous quote that is attributed to too many to credit, but it states, “If you want to write, read.” The same is true for editors. Reading has always piqued his interest and curiosity. But he always remembered that what he was working on was not his book. In his initial relationship with Caro, the editing was fraught, primarily because Gottlieb insisted that the story Caro was telling needed to fit in one volume. The initial manuscript, weighing in at 1,000,057 words, had to be cut to 700,000. A book’s spine can only hold so many words without collapsing. As Gottlieb explained to Caro, “I might be able to get people interested in Robert Moses once. I’ll never get them interested twice.” What made the editing process so hard in this case was that all of the manuscript was interesting. How do you choose what to cut? And that’s why the collaboration was so important. Despite Gottlieb’s duties as president of the publishing house, he always gave Caro his undivided attention.

This was a writing/editing marriage that was emotional, fraught with anger, mutually supportive.

Hilariously, but also on point, is the discussion of the difference in their use of punctuation, particularly the semicolon. Personally, I love the semicolon; it’s a continuation not a stop. Where else will you ever get an in depth look at grammar outside a classroom, and sadly, grammar seems to be a dying art form.

But I could go on and on. This is a deep dive into story and production. By analyzing their relationship, we also get an inside look at Caro’s process and the importance of his historical work and how, with the help of his editor, he honed in on topics of depth beyond his subjects.

There are many informative documentaries out there, but this one is more. My understanding of literature, writing, history, personality, collaboration is all so much deeper after living through dialogues with and about these two giants of 20th and 21st century writing. But, even more important, it’s fun, lively, and humorous. These are important subjects discussed by serious people like Colm Toibin, Bill Clinton, and David Remnick, among others. It’s about process, faith, and loyalty. It’s about a relationship that started when they were young men in 1970 and will last the rest of their lives. But as Gottlieb expressed, it is hoped that at least Caro will live long enough to finish his work. An acknowledgment that editors, even great ones, can be replaced; writers cannot (Note the correct use of the semicolon).

Gottlieb is the more idiosyncratic of the two with interests that extend to ballet and his collection of plastic purses. And he writes as well. But you’ll need to see this wonderful film to put these disparate pursuits in context.

“Turn Every Page” also gives you an introduction to Caro and how he works. For a more complete picture, read his autobiographical book “Working.” It was that book that made me want to read everything he’s touched. I’ve started with the Lyndon Johnson quartet (soon, one hopes, to be a quintet) and am proud to have finished Volume One. I am undaunted by the mountain I still have to climb but am determined to complete the journey.

“Waiting eagerly is not a very proactive line of work.” Gottlieb expressed his relationship with Caro in Shakespearean terms, taken from “King Lear.” “My role with Bob is what Cordelia says is her role with King Lear. It’s to love and be silent.”

Lizzie filmed for five years and finally, at the end, the two Bobs agreed to let her into the editing room but with a major restriction: no sound. Editing is private but even without sound you see them working, discussing fine points, no tempers. Seeing markups lets you know how they approach this dance.

The musical score by Olivier and Clare Manchon is subtly and effectively in the background. Ending with Chet Baker’s “Do it the Hard Way” seals the package.

Opening Dec. 30 at the Laemmle Royal and the Monica Film Center on Jan. 13, 2023.