On this, the 80th anniversary of D Day, it is appropriate to remember all those veterans who sacrificed for our freedom, whether in World War II or in the wars that followed. Beverly Hills filmmaker, Robert Darwell, has chosen to shine a light on African American soldiers, both past and present, to tell us about their experience serving in the military and what it meant to be Black in a sea of white. He has judiciously chosen individuals from each of the past engagements from World War II through the two Iraq conflicts (Desert Shield and Desert Storm), representing the Army, Air Force and Navy. As will become clear, African American soldiers have always had to fight at least two concurrent wars—the fight and the prejudice.

Having reached out to veterans’ groups across the country, Darwell was able to assemble a sympathetic, engaging and diverse group. He was fortunate to find two amazing soldiers who served in World War II, a conflict where the remaining survivors are now well into their later 90s; the last war when the armed services were “legally” segregated. There was very little interaction between the troops with the exception of white officers chosen to supervise and run many of the Black divisions. Every effort was made to keep whites and Blacks separate, from the facilities to the kinds of assignments that were given out to the execution of those jobs.

Romay Johnson Davis, now 104 years old, served in the Women’s Army Corps (WAC) in the postal battalion, an all Black division. She and her fellow WACs were responsible for making sure the mail to and from the soldiers was properly distributed. Thinking about the work she did, there was little that was more important, outside of combat, because the postal workers represented a lifeline for loved ones on both sides of the ocean. For the soldiers, it was their only attachment to family and could not be underestimated. Mail call, as shown in so many movies about the era, brought joy and hope to those receiving letters and disappointment to those who didn’t.

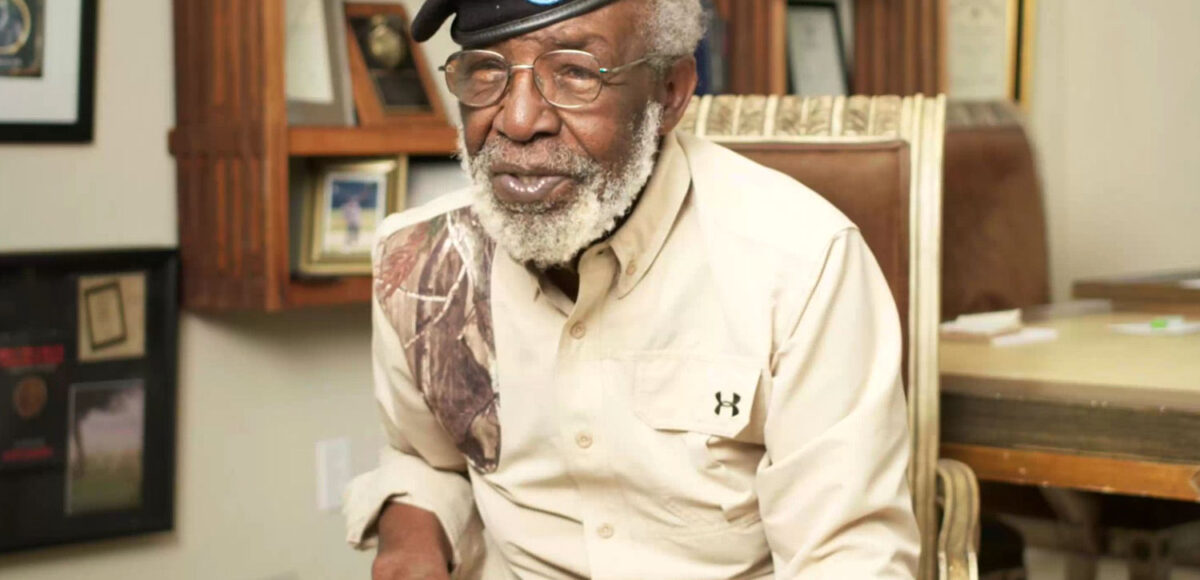

Dr. Eugene Richardson is one of the last remaining famed and vaunted members of the Tuskegee Airmen. Facing the camera in the comfort of his living room, he explains that even as a child he wanted to fly, to be a pilot. The armed forces did not feel that Blacks had the kind of skills that were necessary to become pilots but despite this almost impenetrable wall, a Black division of the Army Air Corps was founded, named after Tuskegee University where many of the pilots trained. The Tuskegee Airmen gave coverage to their all white counterparts in the bomber squads, protecting them from the German air force. Those fighter pilots had no idea that their coverage was from an elite group of Black pilots, pilots whose coverage was highly sought after because of their skill and bravery.

Photos courtesy of Robert Darwell

The representatives from the Korean War are both individuals who should be recognizable, at least for anyone over the age of 60. Both men, now in their 90s, have lived most of their lives in the public eye.

Representative Charles Rangel (U.S. representative of New York’s 13th District from 1971-2017), a high school dropout, was raised by a single mother. Economics played a major role in his enrollment in the army. With limited prospects back home, the lure of an income and possible educational and training benefits after his service was a major factor in his enlistment. He still remembers the feeling of despair as the commanding officers abandoned their primarily Black troops as they were being attacked on all sides by the enemy. Although President Truman desegregated the military by Executive Order, Rangel recalls that his experience was of a distinctly segregated Army.

James McEachin went on to become that rarest of rare creatures, a working actor, recognizable from his supporting work in innumerable television shows, including his own short-lived series called “Tenafly.” McEachin defied the odds in the Army and continued to be a groundbreaker in his personal life. And like everyone else profiled in this documentary, none of it was easy but he was up for the challenge. He eloquently voices the importance of serving. “No veterans, no democracy. No democracy, no America.”

The very unpopular Vietnam War created its own problems, not just in Southeast Asia but also at home where veterans were accorded none of the respect of those who served in previous wars or the ones that came after. The profiled “survivors” of that war had very different experiences.

Ty Martin had the harder row to hoe in a manner of speaking. A sailor in the Navy, he was gay in the era before “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell.” He faced danger around every corner, particularly as a necessarily in-the-closet gay man. He thought that the Navy would make him a man,” that he would no longer be gay.” But it also gave him the opportunity to travel, see the world, and wear those white bell bottoms, things his naive 17-year-old self couldn’t resist. Successfully hiding his sexual orientation, he remembers the camaraderie he felt with his fellow sailors. Now a senior and still handsome, he speaks to us from his apartment in Harlem, surrounded by the African masks he has collected over the years. His overall warmth shines through.

Norvell Ballard enlisted in the Air Force at the age of 17 and soon found himself in the jungle. Seated, not entirely ironically, in front of coffins on display as part of his funeral home business, it is Ballard who talks convincingly and strongly about the benefits that all recruits in the armed forces are entitled to and yet are distributed inequitably. His experience was that the treatment of white and Black soldiers was entirely different. Blacks were expelled for the same actions that resulted in no reprimands for whites.

Roy Wilkins was drafted by the Army at the tail end of the Vietnam War. He was on the cusp of going to college and the military made him an enticing offer. Sign up for eight years and they’d pay for his education. He eventually served in Vietnam and Iraq in the Special Forces. Outgoing and proud, Wilkins has had other battles to fight that were more challenging, as you will see. But even today he’d still recommend joining.

The rest of the veterans profiled served in one or both of the Iraq Wars. Their experiences are as alike as they are different.

Robert Dabney, Jr. also served in the Army. During his 11 years as a medic, he saw action in Saudi Arabia, Kosovo and Iraq, areas he calls the triangle of death. Joining at 17, he was looking for new opportunities that would benefit him and his family. Like Rangel, his motivation was economic, an outcome that was both positive and negative.

Eric Howze, an Army survivor of the Iraq War, has found his most challenging battles at home. Fighting PTSD and depression, he accurately expressed what happens to so many when they are discharged. “Even though you made it home, there’s still a war going on.” A proponent of therapy, he belongs to a group called “No Hero Left Behind” that was fundamental to his healing process. Telling his story of survival and how he has been giving back is inspirational.

Phoebe Jeter is one of the outliers. Career Army all the way, she retired as a Major, having served in both Desert Shield and Desert Storm. She experienced the highs and the lows but is very proud to have been a groundbreaker. She discusses gender politics and the effect it had on her because, as she points out, so many of the best opportunities were offered to men and not women; opportunities that had a clear promotion path like becoming an aide to a general. Her positive and spiritual outlook set her apart.

Julia Robison, who I would describe as a survivor of the Army, had a very different experience. One of 13 children, the Army was an opportunity to find her independence and honor her father who served in Vietnam. She viewed the military as a way to escape the sorrows and suffering she saw around her. As she will eventually explain, what she had to endure in the Army was worse than what she was determined to escape.

And finally, there is Janina Simmons, a groundbreaker in every sense of the term. She was the first African American woman to graduate from the U.S. Army Ranger Corps. Rightly proud of her accomplishments, she is aiming for the top and it’s unlikely that anything will get in her way. Enlisting was pragmatic. She needed the money to continue her education. For her, what matters most was always to try as hard as she could. Out of 370 in her Ranger class, only 80 graduated. An example, at least theoretically, of how far the military has come, she, a gay woman, has been supported all the way in her endeavors.

These are just thumbnail sketches of each individual; the movie offers a more complete and engrossing portrait of each of them. The film highlights the diversity of experience and illustrates how far things have come, although it is also an example of the adage, “the more things change, the more they remain the same.” Darwell has done an excellent job of bringing these stories to life and allowing you, the viewer, to draw your own conclusions. This is engrossing and fulfilling cinema at its best.

Now streaming on Amazon Prime VOD.