The hedges grow taller and broader on the drive up Elden Way as they work to conceal increasingly audacious mansions. The street dead ends in a cul-de-sac, where a Mediterranean-inspired, modified Beaux Arts home stands in stark contrast. Dipping shyly beneath the curb on a gentle slope of a hill, it’s out of place, almost quaint among the monoliths. A modest scrolling wrought iron gate marks the entrance, a portal back to a place and time that was more warm and welcoming.

Beyond it is The Virginia Robinson Gardens (VRG), a living museum offering a rare glimpse into early life in Beverly Hills. The 6.2-acre estate and botanical garden was the residence of Virginia and Harry Winchester Robinson. Built in 1911, it is considered the “first estate” in Beverly Hills. The Robinsons transformed a barren stretch of barley into a series of lush hillsides featuring heirloom varieties and many rare and exotic plants, including the largest king palm forest in the Northern Hemisphere.

Virginia, a legendary hostess and grand dame of her day, is referred to as the “first lady of Beverly Hills.” With the help of a live-in staff of 12, including a cook and majordomo, she threw several parties per week throughout her decades-long residency. She entertained royalty, including the Duke and Duchess of Windsor, and film icons such as Mary Pickford and Mae West, among many others.

The Virginia Robinson Gardens was listed in the National Register of Historic Places in 1978. Since 1982, the museum estate has been jointly operated by the County of Los Angeles and the Friends of Robinson Gardens (FRG), a nonprofit organization, which ensures its funding.

Last year, the city of Beverly Hills expressed interest in taking over operations of The Virginia Robinson Gardens. Los Angeles County was amenable to the idea, and L.A. County Supervisor Lindsey Horvath gave a 180-day deadline for both sides to return to the table with a plan. The Courier recently reached out to both sides for an update. Diane Sipos, superintendent of VRG under L.A. County management, would not comment on the progress of talks. Instead, she would only confirm that VRG is currently operated by L.A. County Parks and Recreation Department. A press spokesperson for L.A. County said, “We are currently in discussions with the city of Beverly Hills, and we have no further comments until these discussions progress further.” As for the city of Beverly Hills, “Discussions are ongoing,” said Keith Sterling, Beverly Hills Deputy City Manager, adding, “As you might imagine, there are several complex logistical elements, and the process is taking a bit longer than anticipated.”

No matter who ends up running operations, there’s no denying that The Virginia Robinson Gardens and its former inhabitants are inexorably linked to the city of Beverly Hills.

PHOTOS COURTESY OF the VIRGINIA ROBINSON GARDENS ARCHIVE

The only way for the general public to experience this gem is to book a spot in advance on a docent-led tour ($15 per person) around the grounds. While the botanical tour focuses solely on the gardens, the 90-minute historical tour offers a stroll through the various terraced landscapes, as well as a peek inside the lives and living spaces of these Beverly Hills pioneers.

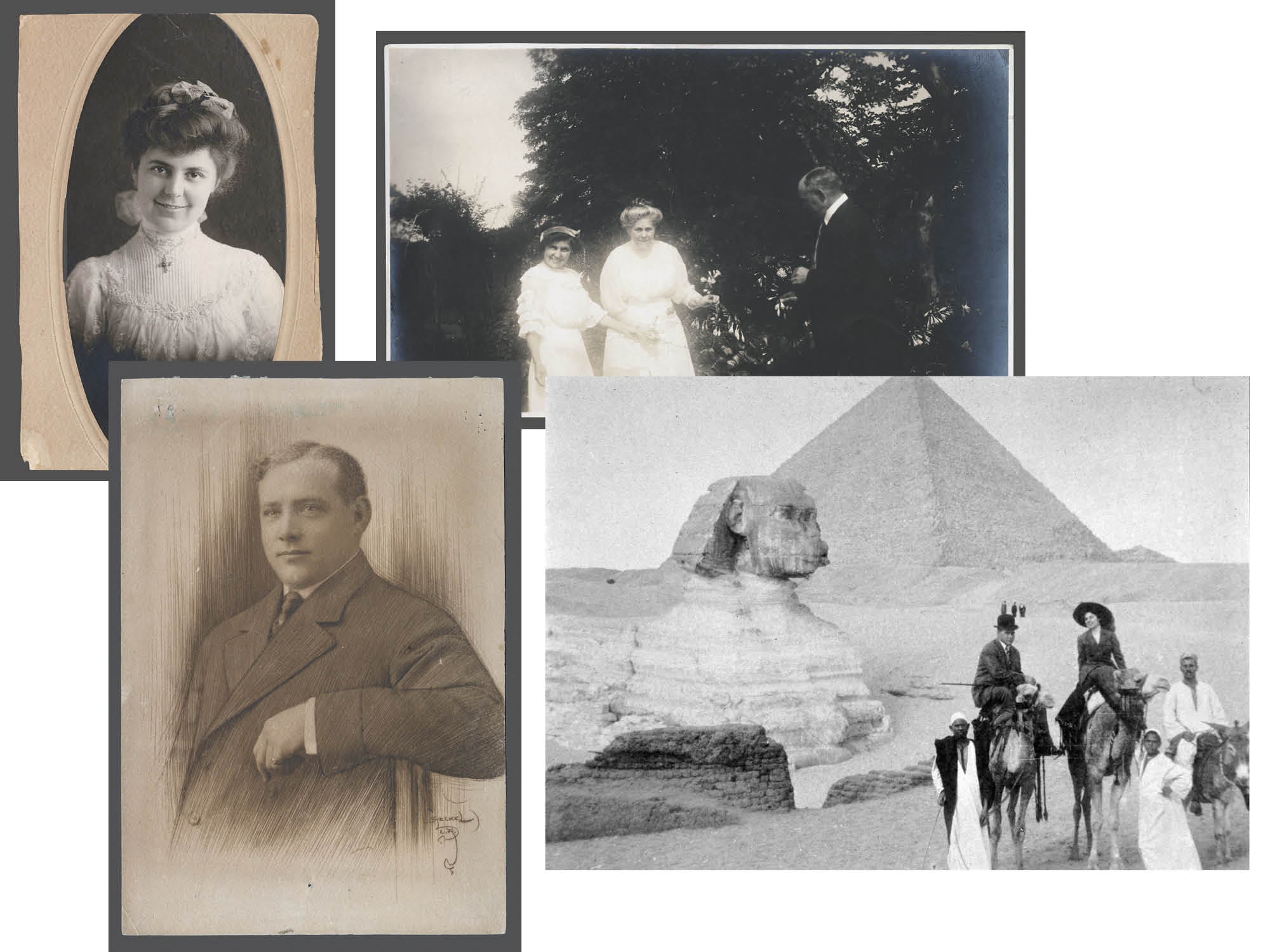

Virginia Catherine Dryden, born in 1877, was the daughter of Nathaniel Dryden, a self-taught architectural designer and building contractor. Three of his designs have since made the National Register of Historic Landmarks. Virginia’s uncle was Leslie Brand, the railroad tycoon and developer later dubbed “the father of Glendale.”

Harry Winchester Robinson was born in 1878 into a mercantile family dynasty. His grandfather had built Boston Dry Goods, which, under Harry’s father, Joseph Winchester, became the upscale, turn of the last century downtown department store J.W. Robinson, which Harry would later helm. A few decades and mergers later, it evolved into the store known as Robinsons-May, the last of which shuttered in 2006.

As the offspring of two prominent Los Angeles families, Virginia and Harry naturally traveled in the same high-society circles. Still, their wedding in November 1903 came as a surprise; it took place just six days after their engagement announcement was printed in the Los Angeles Times.

Following the young couple’s honeymoon, they embarked on a series of trips that spanned several years and the globe—with extended visits to Europe, Egypt, India, China, Japan, South America and other far-flung locales. While away on one such lengthy adventure, a new town was slowly springing up in the shrub brush of Los Angeles. The pair were surprised to hear about it upon their return, and with curiosity piqued by the rumor it was to be the site of the relocated Los Angeles Country Club, Mr. and Mrs. Robinson set out to find the newly developed Beverly Hills.

What Virginia and Harry discovered on their fateful twilight drive in January 1911 was a golf course under construction amid vast empty tracts of land. “We never found the club,” Virginia would later tell a reporter, adding, “But we found ourselves on a slight hill with a lovely view of rippling wheat fields and the mountains. A full moon was shining down, and Harry said, ‘This is where we are going to live.’” The following day, Harry went to the Rodeo Land and Water Company and, by 10 a.m., had purchased the parcel for $7,500 from Burton Green. Virginia later recalled, “Burton Green had built Beverly Hills. But there wasn’t one house here. There wasn’t a single thing out here. Just a little bit of a real estate office, kind of a shed, on Santa Monica Boulevard.”

Once the deed was in hand, Virginia’s father quickly set about designing and constructing the couple’s home. By September 1911, the “L” shaped, 6,000-square-foot house was completed. The earliest photo shows the flat Italianate-style villa, with a parapet of cast stone balustrades and a column-supported portico, squatting on a dusty, barren hilltop. A straight concrete path led from the dirt street to the front steps—no hedges or fence. Privacy wasn’t an issue; nobody lived in Beverly Hills yet. The grounds consisted of little more than a meadow in front and a great lawn at the back (both sodded), a tennis court and, the following year, a small lap pool.

BOTTOM: VIRGINIA (LEFT) AND HEDDA HOPPER IN THE 1960S

PHotos courtesy of the Virginia robinson gardens archive

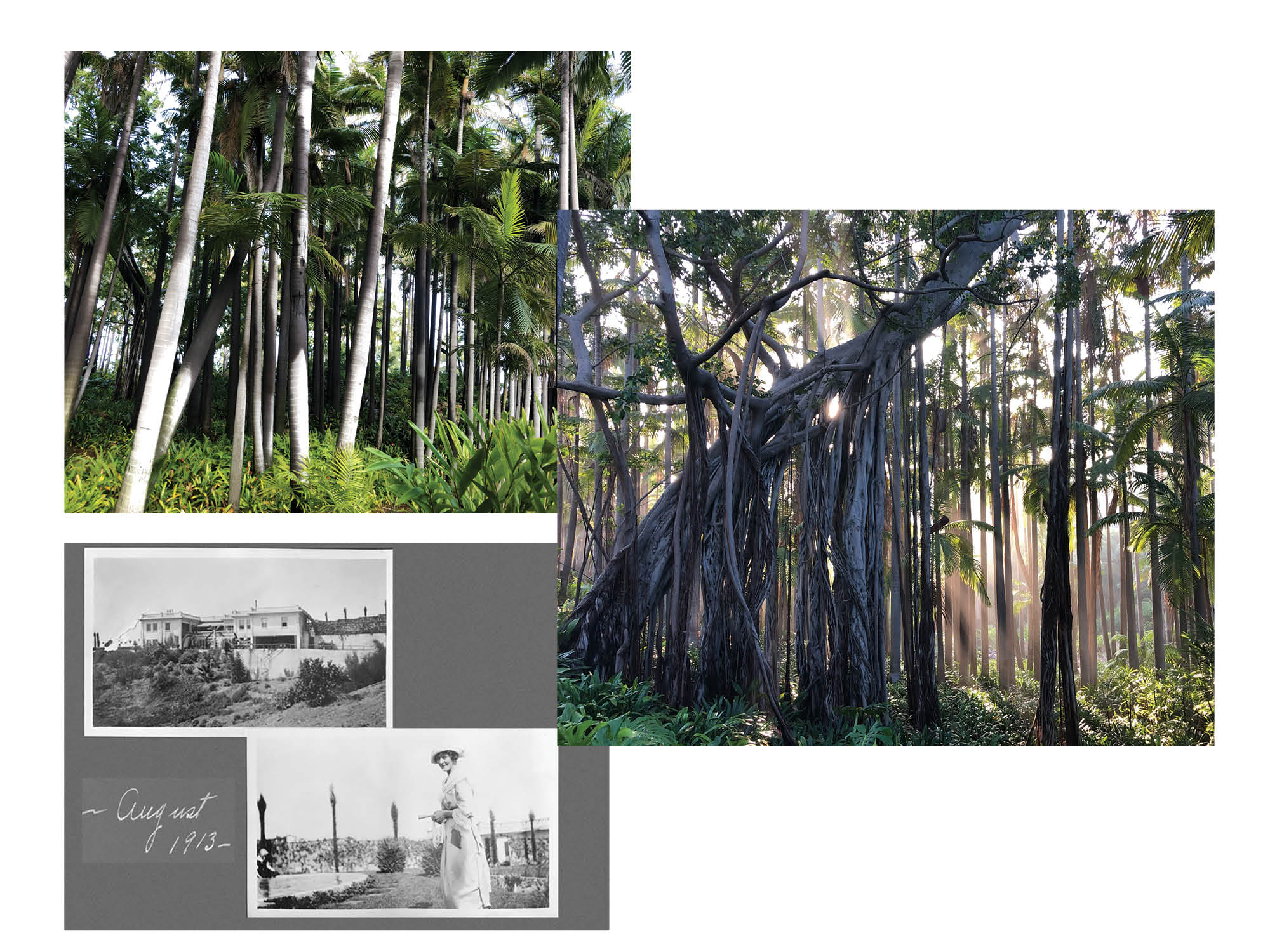

Around this time, due to this unique temperate zone, the banyan trees planted sometime in the ‘30s began sprouting aerial roots, which only happened in their native habitat. Today, they make for a dramatic sight. The long fibrous roots of these old trees now stretch close to 30 feet, cathedral-like buttresses that lend a hallowed feeling to the grove. Nearby, a massive eucalyptus tree, the last remaining from the first flats of trees Virginia and Harry had purchased over 100 years ago, rises like a skyscraper.

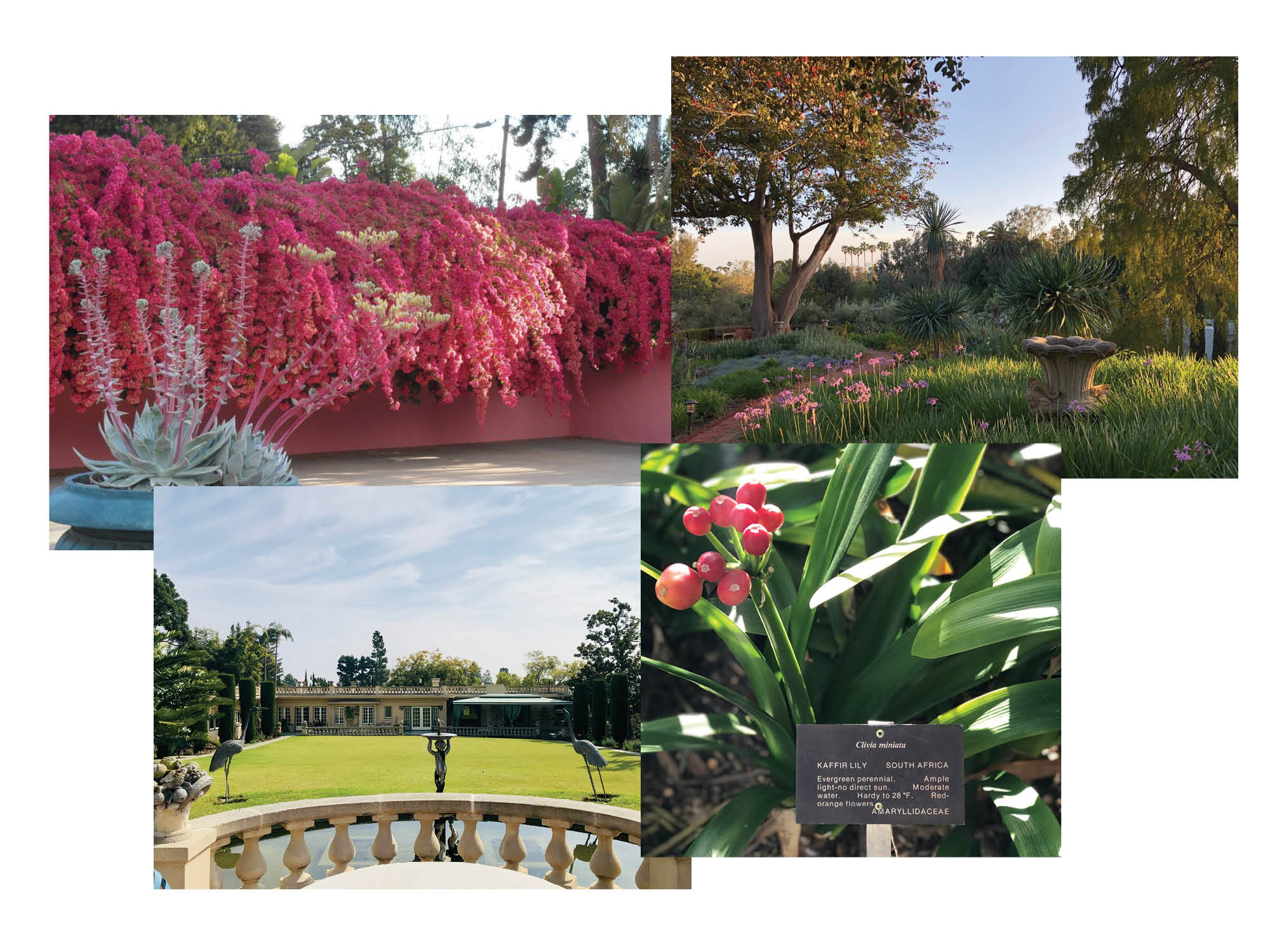

The King Palm Forest is just one of five gardens developed in various but distinct stages over five decades. Great care is taken to maintain these areas, which are currently managed as historic display gardens by FRG. If plants need replacing, they’re swapped with identical species wherever possible to preserve the couple’s original intent for the gardens and landscaping.

Completed in 1935, the Italian Terrace Garden is the largest, covering over two acres. It’s composed of several descending brick-paved terraces connected by a series of winding paths along a central axis per Neoclassical Italianate style. An intricate water system was designed to flow down the terrain, trickle along runnels carved into the bricks and stone, and cascade into a series of waterfalls before emptying into various pools and fountains. The runnels were inspired by the Alhambra in Spain, where Virginia and Harry marveled at the soothing melodies of the gently moving water. Perhaps inspired by those memories, Virginia added the Musical Stairs, a water feature made from inverted terracotta roof tiles laid in a series of steep steps, designed to produce a different note as water moves from one step to the next.

Sadly, Harry would never see these formal gardens take shape.

He passed away on Sept. 19, 1932, but not before spending much of his final week with the woman he adored in the gardens they loved. His widow preserved these last days in a diary, pressing leaves and flowers into the pages for that week in September, along with the simple inscription: “With Harry in the garden.” The entry for Sept. 19 was left blank.

For two years, Virginia mourned, stepping back from civic engagements. To process her grief, she renewed her interest in finishing the gardens as an homage to her late husband. She also began writing a series of letters to him after his death, which she continued for five years. Most often, they were to ask his advice about the garden, tinged with loss and longing.

MIDDLE: THE BANYAN TREES

BOTTOM: THE LANDSCAPE PRIOR TO THE KING PALM FOREST PLANTING (LEFT) AND VIRGINIA STROLLING ALONG THE GREAT LAWN, BOTH FROM AUGUST 1913

Top and Middle PHotos by Joshua Johnston

Bottom PHotos courtesy of the Virginia robinson gardens archive

“Harry, do you like the trimming on the west side?” She asked her husband in a letter dated December 1932. “I cut the oaks down–it’s much neater, but I cried after I did it because it’s different [from] when you last saw it.” Daunted by the scale of the Italian Terrace Garden during its construction, she looked to Harry for reassurance in another posthumous letter, dated 1934: “My darling – am I making a mess of our earthly paradise? You guide–kiss me again.” Virginia continued to work on her gardens for the next few decades, through these preserved letters, we know Harry’s spirit was with her during their entire creation. In part to fill a void left by her beloved husband, Virginia began to reinvent herself in the mid-1930s. She joined the Board of Directors of J.W. Robinson in 1935 (a rare position for women in those days) and served until 1960. She also began to host luxurious parties, many of them charitable functions, up to four a week. Some were grand affairs on the great lawn with hundreds of guests; others were intimate luncheons in a garden nook and all manner of gatherings. She continued this for decades. Of course, she had help; Virginia maintained a staff of a dozen live-in helpers for her 6,000-square-foot home, including a majordomo, an assistant butler, five gardeners, a cook, a kitchen maid, a houseman and a personal maid.

Her reputation and the high standard for gracious living she set solidified her place as “the first lady of Beverly Hills.” As such, over the years, she entertained the likes of the Duke and Duchess of Windsor for tea alfresco; Walt Disney’s widow, Lillian, celebrated her marriage to her new husband in Virginia’s backyard. Mae West whispered naughty jokes to the hostess from the living room couch while Hedda Hopper dished out gossip on fellow guests, most of them Golden Age stars like ClarkGable and Fred Astaire, during the extravagant affairs. So large were her parties, Virginia had to remodel parts of the home to accommodate the throngs. A large terrazzo terrace opening to the great lawn was added at the back of the home. The narrow front entryway, which often bottlenecked when partygoers arrived, was widened.

The last changes to her estate were mainly decor updates to the interiors of the main residence in the 1950s. The gold curtains and sleek, matching sofa and chairs in the Gold Room call to mind Jackie O’s revamp of the White House and channel the same austere luxury. Thousands of old, leather-bound books collected from the corners of the Earth line the library’s walls. The home is an eclectic repository of souvenirs, art, photo albums and guidebooks from the couple’s extensive trips. These mementos survived and still make up a large part of the decor—ancient artifacts from Asia, like bronze sculptures of multilimbed deities, decorate tables and shelves. If the mashup is confusing, remember these are objects cultivated from a well-lived and well-traveled life that spanned from the Victorian era to the space age.

Virginia Robinson passed away just weeks short of her 100th birthday in 1977. Upon her death, the entire estate was bequeathed to the County of Los Angeles in hopes that what she referred to as her “life’s work” could be shared with the public and future generations.

Repairs and maintaining the estate would be costly, but it received early support from the L.A. County Supervisor at the time, Edmund D. Edelman. He and the Board of Supervisors placed the estate under the auspices of the Los Angeles County Arboretum and Botanic Gardens. Edelman then enlisted Joan Selwyn, a leader in the arts community, to form an organization of activists to support the restoration project. He proposed a partnership.

Selwyn created “Friends of Robinson Gardens” in 1982 with a Board of Directors and a general membership of over 75 committed women. The FRG would become the major source of fundraising to restore and maintain the garden estate, while L.A. County would run the day-to-day operations. A letter from President Ronald Reagan that year called the partnership a fine example of what can be accomplished through cooperation between the private and public sectors.

BOTTOM LEFT: THE GREAT LAWN TODAY; BOTTOM RIGHT: A kaffir lily from south africa

Top Photos by Joshua johnston; Bottom photos By Linda Immediato

Metal leaves engraved with the names of FRG supporters, among them Barbara Streisand, hang on a decorative steel tree sculpture at the back of the residence.

According to Patty Elias, FRG Board Member and archive coordinator, the organization has restored all of the historic buildings on the property, to the strict standards of the Department of Interior, in the decades since. Additionally, Elias said that despite delays caused by COVID-19, FRG was able to fund and complete phase two of the Historic American Landscapes Survey (HALS). The Virginia Robinson Gardens is in the process of applying for museum accreditation and the HALS report will provide the landscape documentation necessary for the museum status application.

While the future of its operations has yet to be decided, if you make it up to the end of Elden Way, try to imagine nothing was there before. And remember that many of the living things—the scented Eiffel Tower roses, the majestic eucalyptus, the King Palm Forest and old banyan trees—were planted there by the Robinsons with love and still stand before you now inspiring wonder, over a century later.