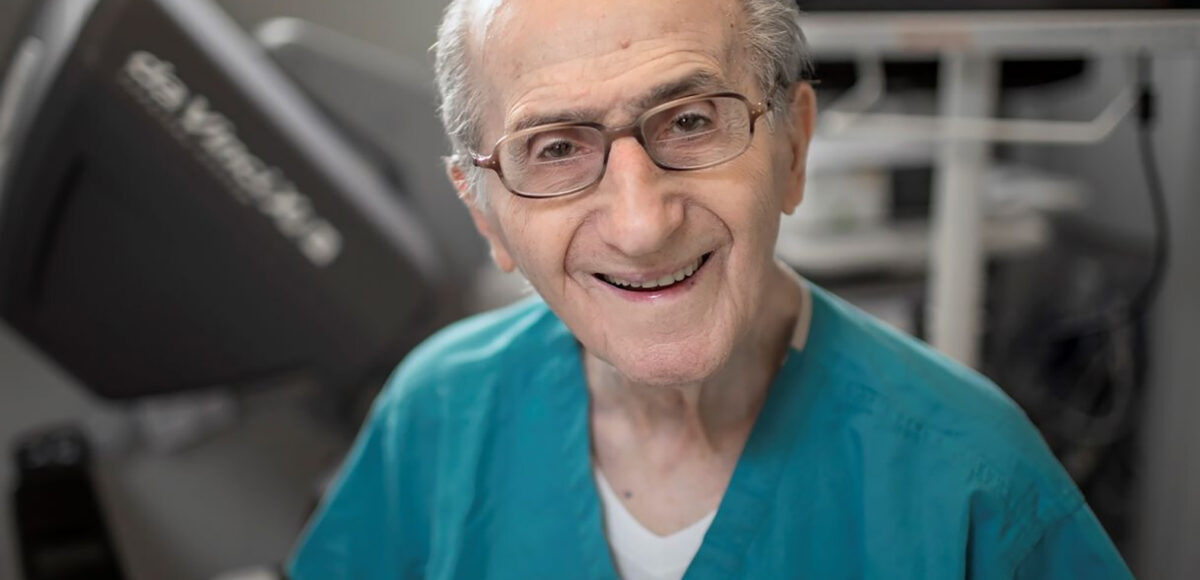

Dr. George Berci passed away on Aug. 30 at the age of 103, ending a distinguished career as a groundbreaking innovator who revolutionized the field of endoscopic surgery. A gifted violinist who chose medicine at his mother’s urging, Berci arrived at Cedars-Sinai in the 1970s and remained actively engaged into his 100s as an educator and senior director of Surgical Endoscopy and Innovation Research.

“George was a towering figure in our profession,” said Edward H. Phillips, M.D., executive vice chair of the Jim and Eleanor Randall Department of Surgery. “His profound legacy lives on in the hundreds—if not thousands—of medical students and surgeons influenced by his innovations and ideas.”

Berci’s designs and use of micro-instrumentation—including fiber optic-based lighting and cameras—paved the way for the development of endoscopic and laparoscopic surgery.

Berci’s influence and achievement in the field are all the more extraordinary given that medicine was not his primary passion during his formative years. The son of the assistant conductor of the Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra, Berci showed considerable promise as a violinist and could play concertos by age 10.

Berci’s professional path was stalled by the outbreak of World War II, when he was forced to work as a laborer for the Nazis.

“Unfortunately, I had a terrible early life in respect to being a Jew,” said Berci, who often shared his story of survival with student groups at the Museum of Tolerance in Los Angeles.

In the summer of 1944, Berci and hundreds of other conscripted Jewish laborers were packed onto a train destined for the death camps. The train stopped near the Hungarian capital during an air bombardment by British and American forces, which caused guards to flee.

“Everybody disappeared,” Berci recalled. “So, we disappeared, too.”

Soon Berci was recruited to work for the Hungarian underground and became part of a large-scale operation of forging papers. The network was organized by the Swiss Vice-Consul Carl Lutz, who helped save thousands of Hungarian Jews by issuing false protective letters.

After the war, Berci remained in Hungary and earned a medical degree from the University of Szeged in 1950. He continued surgical training before moving in 1953 to Budapest, where he helped establish an experimental surgical division. In 1957, Berci, who did not then speak English, moved to Australia after being awarded a Rockefeller Foundation fellowship in the Alfred and Royal Melbourne hospitals. In 1967, he was recruited to join the Cedars-Sinai Department of Surgery. Several years later he joined the faculty as full-time director of a multidisciplinary surgical endoscopy unit, a new idea at the time.

Berci’s vast contributions to medicine brought him significant acclaim, including Cedars-Sinai’s Pioneer in Medicine Award and the Jacobson Innovation Award from the American College of Surgeons.

He is survived by four children and six grandchildren.