The most important story we will ever tell is our own. Yet, for a variety of reasons, most of us fail to give that task its due. In his latest book, For You When I Am Gone: Twelve Essential Questions to Tell a Life Story, Steve Leder argues that a thoughtfully told life story is one of the most valuable gifts that we can leave behind and one of the most important ways we can be sure to live our truth now.

His advice on how we should write that story is both practical and profound.

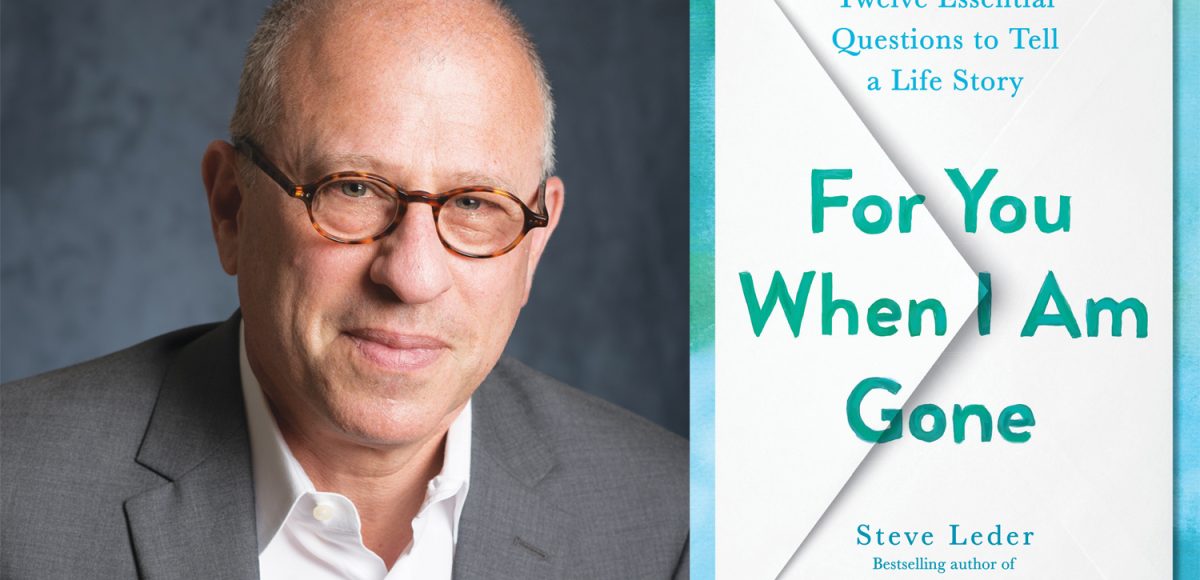

As Senior Rabbi of the oldest, largest and most prestigious synagogue in Southern California, Leder is a beloved local spiritual figure with a national profile. Like his four other books (two of them best sellers), For You When I Am Gone draws upon more than three decades of experience as a rabbi. This book was inspired by the thousand or so eulogies Leder has written after meeting with family members of the deceased. Over the years, he has become an expert in piecing together the key points of a life’s legacy.

“If you ask the right questions, everyone’s life is hilarious, sad, adventurous, foolish, and wise; everyone’s life is interesting,” Leder writes. “Everyone’s life is a textbook about your own life. Hearing other people’s stories has enriched my life, informed my life, and ennobled my life.”

Nonetheless, the central thesis of For You When I Am Gone is that it is better for us to tell our own story. To do so, Leder recommends a device known as an ethical will.

Unlike an actual last will and testament, an ethical will holds no legal significance. It won’t transfer any real or personal assets. Yet, what it does convey is many times more valuable; namely, the lessons of a life lived well or even not so well. In creating a document that contains the stories, regrets, challenges and successes that have shaped our life, we can pass on lessons learned to the next generation.

As Leder writes in the book’s introduction, “It is a way of saying not only that we, the storyteller matter, but even more so the beloved listener. To share our story with someone is to say, you matter to me. And if we do not tell our story, who will?”

The concept of ethical wills dates back to the ancients and has long been part of the Jewish tradition. Leder himself has conducted workshops on writing ethical wills for some time. He wrote about the practice in his last book, The Beauty of What Remains: How Our Greatest Fear Becomes Our Greatest Gift. This book goes a step further, serving as a how-to manual for gathering material to include in the document.

For You When I Am Gone is divided into 12 chapters, each representing a key question to contemplate when preparing an ethical will. The questions include topics most would just as soon not dwell upon, such as “What Do You Regret?” “What Was Your Biggest Failure?” “Have You Ever Cut Someone Out of Your Life?” and “What Got You Through Your Greatest Challenge?”

Other questions conjure up the best things – and best moments – in life: “When Was a Time You Led with Your Heart?” “What Makes You Happy?” “What Is a Good Person?” and “What Is Love?”

Still others call for reflection on what we will leave behind, such as “How Do You Want to Be Remembered?” “What Is Good Advice?” “What Will Your Epitaph Say?” and “What Will Your Final Blessing Be?”

Leder notes that while details of each answer will be personal to the writer, there are universal elements of the human experience, such as love, forgiveness and the strength of family ties that inevitably shine through.

That is what makes this work so powerful, even at the modest length of 216 pages.

The strength of For You When I Am Gone comes in the weighty examples Leder uses to illustrate each chapter. He asked a disparate group of friends to answer the questions posed in the book, which he reprints anonymously. Members of the group come from different ethnicities, religions, professions, sexual orientations and levels of fame and fortune. One suspects Leder may have chosen the respondents for their richly textured lives. But that really doesn’t matter. What does matter is that all shared themselves so selflessly. Each chapter is filled with voices that are raw, humorous, contemplative and deeply thoughtful.

Vignettes begin with lines such as “I wish I had gotten better therapy earlier,” “I came out as a gay man in my mid-thirties,” “My greatest challenge in life has been my battle with alcoholism and addiction” and “I fail every day – often publicly and in big ways.”

It is at times unsettling to peer into lives that we do not know. But it is obviously a testament to the esteem in which Leder is held that the participants lay themselves so bare. Leder himself ventures into details about his own life – including the complicated relationship with his late father – that many would be uncomfortable sharing.

But that is precisely the reason why the book succeeds.

It is both humbling and thought-provoking to read the examples provided by Leder and the others. Reading them demystifies the concept of writing an ethical will. In fact, it is impossible for the reader not to contemplate one’s own responses to those 12 essential questions, compiling the material for an ethical will of our own.

In the introduction to For You When I Am Gone, Leder said he believed he was imposing on his busy set of friends when he asked them to participate in the book. By the end of the exercise, every one of them expressed their gratitude to him instead.

So will readers.

For You When I Am Gone: Twelve Essential Questions to Tell a Life Story is published by Avery, an imprint of Penguin Random House.