I’ve had very few heroes in my life but Bill Russell was always one of them. Although my husband, who played basketball through college (let’s not get excited here, it was Pomona College before Greg Popovich was there) always came down on the Wilt Chamberlain side but not me. My hero worship had very little to do with basketball. For me, it was Russell, the man. Make no mistake. It didn’t hurt that he was an Adonis, but it was the justice he stood for, all 6-foot-10-inches of him and more. It’s the same reason I revere Kareem Abdul Jabbar.

Director Sam Pollard had a mighty task in front of him when he was approached to make this documentary. His goal was to make sure that the younger generation of basketball fans was aware of his groundbreaking career both on and off the court. Using players of today like Steph Curry, Chris Paul and Jalen Rose as well as superstars of yesterday like Larry Bird, Oscar Robinson, Julius “Dr. J” Irving, Bill Walton, Magic Johnson, Jerry West, and Kareem Abdul Jabbar among others, they paint a portrait of the man and his lasting influence.

This two-part series on Netflix plays out chronologically beginning with his family’s move from Monroe, Louisiana to Oakland, California. Russell’s father Charles was his first example. He was denied a raise at the factory where he worked because, as his boss explained, casually using the N-word, he couldn’t give him the same money as a white man. Enraged, he returned home and explained to his family that he would have to leave this small town in the racist South because either he was going to kill someone or someone would kill him. Leaving on a train to California was Bill’s first adventure at age 9. His prized possession, obtained shortly after moving to Oakland, was his library card. He spent countless hours there studying other worlds, worlds that someday he would conquer.

He was relatively late in picking up a basketball and he had his fans and detractors in high school. Cut from the junior varsity team, the varsity coach immediately grabbed him and he began to shine. It was here that his defensive run and jump style was born. He was overlooked by every college with one exception. That exception was the University of San Francisco, a small Jesuit school, that offered him a full scholarship. It was the best decision that either ever made because by his junior year they won the NCAA championship and repeated the next year. He was aided greatly by his coach, Phil Woolpert, who used the best players he had regardless of color. At one point, he started three African Americans, Russell, K.C. Jones (who would later be a teammate on the Celtics), and Hal Perry. He and the team were supportive of Russell and his Black teammates when they faced racism on and off the court.

The next part, perhaps the most important, of Russell’s life was about to begin. Red Auerbach of the Boston Celtics was bound and determined to draft Russell for his team. What the Celtics needed was a tough defender and an ace rebounder. Their chances of grabbing him in the draft were slim. The Rochester Royals had first pick and they had already indicated it would be Russell. Acting fast, the owner of the Celtics, Walter A. Brown, went to the owner of Rochester and struck a deal. Brown also owned the Ice Capades and offered him as many guaranteed performances as he wanted for his stadium if they would not take Russell. So, in a way, the Ice Capades were traded for Bill Russell.

But before starting the Celtic’s 1956-57 season, Russell had one more feat to accomplish – competing for the U.S. at the Melbourne Olympics. Voted captain, the American team beat the Soviets for the gold medal. As Russell recounted, “For one brief moment you are the best on earth.” Now his pro life could begin.

He didn’t exactly light up the courts at the beginning. For the first time in his sports life he questioned his ability to make a difference. It was Auerbach who changed it around for him when he explained that he wasn’t on the court to score; he was there to block shots and dominate the defense. With Auerbach’s approbation, Russell was able to ignore the hostile, racist Boston press and skeptical fans and start doing what he was there to do: defend, force turnovers, block shots, and rebound. Boston, a team that had always been high scoring with star Bob Cousy, Bill Sharman and Frank Ramsey, now had more defensive depth.

Russell and his bride, college sweetheart Rose Swisher, moved to the suburb of Redding. The level of racism directed at them came as a surprise. Boston would always be challenging from the standpoint of prejudice but in this, like every other barrier that came his way due to his color, he refused to be a victim. The chasm between his life on the Celtics and his life in Boston could not have been greater.

Russell thrived under the system devised by Auerbach who assigned court time based on who was the best for the position and the play. He never allowed race to be a factor and Russell noticed that right away, creating an unbreakable bond with his coach. But it wasn’t just a bond between player and coach, it was a bond between the rookie and the established team. They were brothers and the chemistry and camaraderie between them was palpable. They were almost telepathic in their communication with Russell on the court for what they needed from him. Finishing strongly in the regular season that year, Boston won their first ever NBA Championship against the St. Louis Hawks. It was the first of many spearheaded by Russell who would become the captain of the team. Auerbach was right. Russell was exactly what the team needed. They would go on to win eight straight championships.

The 1959-60 season was a game changer with the arrival of the 7-foot-1-inch Wilt Chamberlain. Towering over Russell at center, Russell altered his defensive play accordingly. Their rivalry would be famed throughout the league.

Chamberlain played for the Philadelphia Warriors, an inferior team that he made competitive. But Russell played with a group of great athletes who played as a team. The press may have dubbed Cousy the star but he regarded himself as a member of a well-oiled machine that played for the greater good – winning.

The other major rivalry was against the Los Angeles Lakers led by Jerry West and Elgin Baylor. During Russell’s tenure with the Celtics, they met the Lakers six times in the finals, defeating them all six times, even in 1969 when the Lakers had added Chamberlain to their roster. That Russell-Chamberlain rivalry was transformative for the NBA, an “also ran” in the sports field. By the end of the 60s, the NBA had replaced Major League Baseball in popularity.

The deciding factor for Celtic dominance was always Red Auerbach, the first coach to field an all Black starting lineup in any professional sport. Unapologetic, Auerbach went with the best players for that game.

Russell, whose ability was demeaned by the Boston press from the moment he arrived on the scene, was deemed to be surly and uncooperative. Russell did not suffer fools and spent no time catering to the writers. After 1964, he decided that he would no longer sign autographs, not for teammates, fans, the press, or even the President of the United States if he asked. “You either buy me as Bill Russell the man or you don’t. My signature isn’t going to make any difference and the fact that I’m a basketball player is just an accident.” He also stated, “I am a public property when I play. I am a private property when I’m not playing.” Russell would control his own narrative; it would not be dictated by others.

When Auerbach decided to retire, the biggest question was who would succeed him. The first person he approached was Russell but he refused. Auerbach knew he needed a coach that Russell respected and reached out to the ones who might be willing or available but none said yes. When it finally came down to a coach that Russell disliked intensely, he gave in and agreed to be the player coach. Auerbach and owner Walter Brown drafted the first Black player (Chuck Cooper) in the NBA; they made history again by hiring Russell as the first Black coach. Russell forever credited the two as being uniquely equanimous and supportive of him as a person and an athlete.

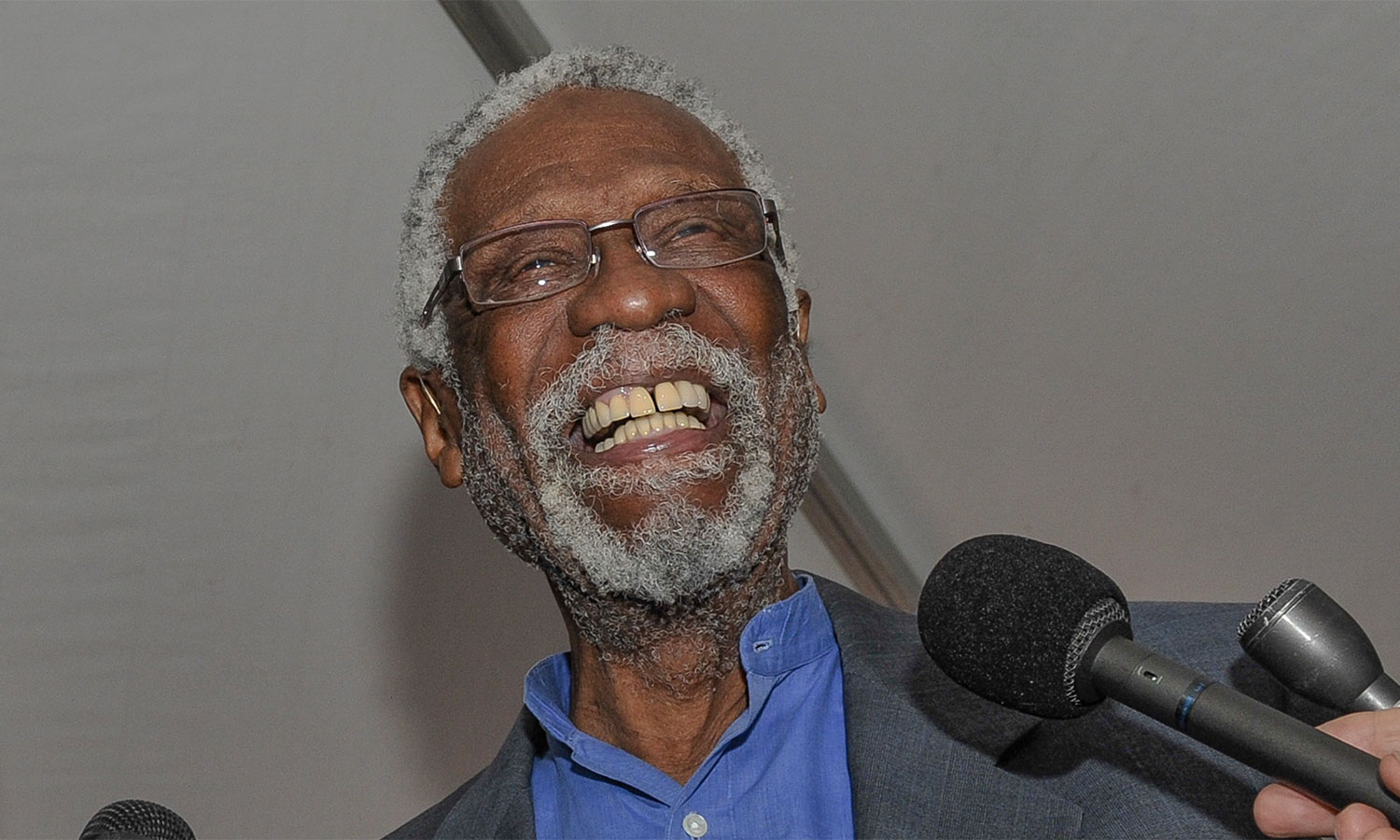

The film footage of all those historic games, the home movies illustrating the relationship between the players, the invaluable interviews with players past and present commenting on his play, the Celtics’ dominance, and the camaraderie that made all the difference is priceless. Watching a still bitter Jerry West talk about all those times he and Elgin Baylor came up on the losing end of the Celtic stick even when they had the better team is both hilarious and heartbreaking. It’s as if their final matchup in the 1969 finals was yesterday. Even better, adding to the footage of Russell speaking at the time about his role as a player, a coach, and an activist, Pollard scored the last interview with Russell before he died, whose comments were as invaluable as his ever present laugh.

I loved seeing that footage and hearing NBA All-Stars and Hall of Famers talk about what made Russell so extraordinary as a player and then a player-coach. But that’s not why Bill Russell is my hero.

Bill Russell faced down the indignities of racism every day of his life. Like his father, he vowed early on that he would not be a victim. When the citizens of Reading signed a petition against him buying a house there, he ignored it and exhorted his wife to keep moving forward. When he was belittled by the Boston press for multiple reasons, he moved on. When his home was vandalized in a most horrific manner, he refused to play the victim even after the police made only a cursory investigation and declared they had no idea of who could have done it. It wasn’t the first time that the police didn’t investigate a crime against the Russells. He would never allow the press or anyone else, for that matter, to be the final judges of his career and who he was.

It was his quiet social activism that attracted me. Supporting the civil rights movement and Martin Luther King, Jr. in particular was not a popular position for a professional athlete. He didn’t care. In 1963, when Medgar Evers was assassinated in Mississippi, Russell called Evers’ brother Charles and asked what he could do. As a result of that call, Russell went to Mississippi, at great risk to his life and career, and set up an integrated youth basketball camp, the first of its kind. He made himself available to Evers for whatever was needed.

If he perceived racial abuse, he stood up against it. He participated at the Cleveland Summit to support Muhammad Ali and his decision to refuse the draft. He attended the March on Washington. But when King invited him to sit on the dais, he refused, indicating that King’s message should not be diluted by the attention that would be accorded to someone whose only credential was his celebrity. Both Russell and Chamberlain were disappointed but not surprised when the NBA refused to call off a game between Chamberlain’s Lakers and Russell’s Celtics the day that King was assassinated. Most recently, he posted a photo on social media of himself taking a knee in honor of Colin Kaepernick and all those with the courage of their convictions.

He was private. He knew who he was and cared little for public opinion, especially as shaped by the sports writers of his day who were offended by his lack of cooperation. He made it clear that he played for the Celtics, not for the city of Boston. And when he played and coached his last game, he left. It would be decades before he returned. He refused to be honored by organizations that subtly or overtly did nothing against racial abuse. When Boston retired his jersey, he didn’t return. When the NBA inducted him into the Hall of Fame, the first Black player to be accorded that honor, he refused to go because it was barely short of criminal that he should have been the first. Eventually he relented and returned when the Celtics re-retired his jersey in 1999 and when he was inducted into the Hall of Fame in 2021 as a coach. In the end, the NBA retired his jersey number (6) and named the NBA Finals MVP award in his honor.

He wrote several autobiographies from which passages are read by actor Jeffrey Wright, but one of the best quotes from his book “Red and Me” was “Whenever I leave the Celtics locker room, even heaven wouldn’t be good enough because anywhere else is a step down.” Bill Bradley, New York Knicks Hall of Famer, one of the many basketball superstars interviewed in the film stated categorically, “Russell was the smartest player ever to play the game.”

The production values are terrific and the voice-over narration by Cory Stoll is strong and authoritative. The choice of interview subjects is superb. Particularly interesting are the comments by his daughter Karen, a lawyer, that put much of the history in perspective. A bit rushed or glossed over are the years when he precipitously left Boston and his family, with only a superficial recounting of the coaching jobs he held after Boston. Still, given that the multiple lives of this iconic superstar could easily fill six hours rather than the three on offer, it’s a pretty good start. I’ve only scratched the surface. Whether you’re a basketball fan or not, there is much to enjoy and learn.

I’m still a fan of the man, who died in 2022. I couldn’t agree more with President Obama who said, in awarding him the Medal of Freedom in 2011, “He endured insults and vandalism, but he kept on focusing on making the teammates who he loved better players and made possible the success of so many who would follow.” He added, “He is the best of who we are. The best of who we aspire to be.”

Russell, in talking about himself said “I can honestly say I’ve never worked to be liked. I’ve only worked to be respected. I have fought in every way I know how. I’ve fought because I believed it was right to fight. No man should fear the consequences because every man should do what he thinks is right.”

Premiering Feb. 8 on Netflix.

Neely Swanson spent most of her professional career in the television industry, almost all of it working for David E. Kelley. In her last full-time position as Executive Vice President of Development, she reviewed writer submissions and targeted content for adaptation. As she has often said, she did book reports for a living. For several years she was a freelance writer for “Written By,” the magazine of the WGA West and was adjunct faculty at USC in the writing division of the School of Cinematic Arts. Neely has been writing film and television reviews for the “Easy Reader” for more than 10 years. Her past reviews can be read on Rotten Tomatoes where she is a tomato-approved critic.