Featured Stories

On the morning of April 25, students at UCLA established a “Palestinian Solidarity Encampment” in

As one of its first actions after installing a new mayor and two new members,

Featured Stories

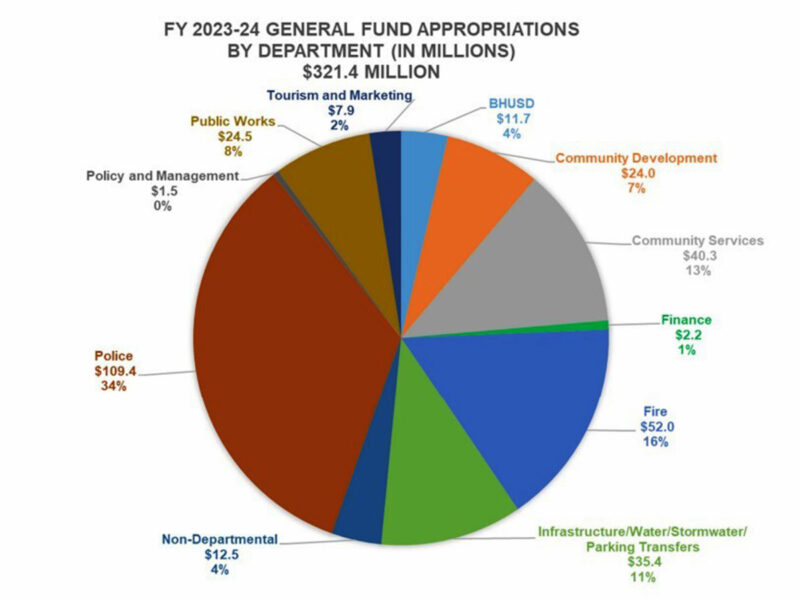

With flush coffers thanks to a post-pandemic boom in revenue, the Beverly Hills City Council

Two and a half years since adopting a mixed-use ordinance, the Beverly Hills City Council

Captured By The Courier

coming in the courier

Sign up for the latest breaking news affecting Beverly Hills and surrounding areas.

By signing up, you agree to our Terms of Use. We never share your data and you may unsubscribe at any time.

Latest Videos

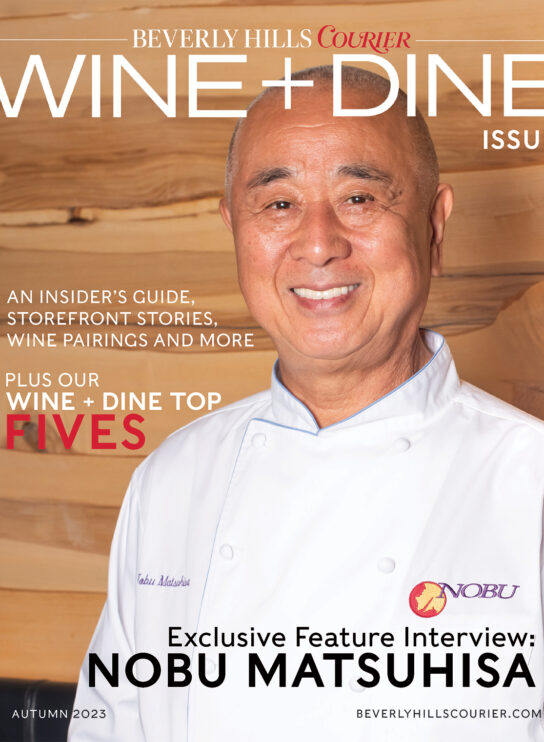

Feature Interview: Nobu Matsuhisa | Beverly Hills Courier Wine + Dine

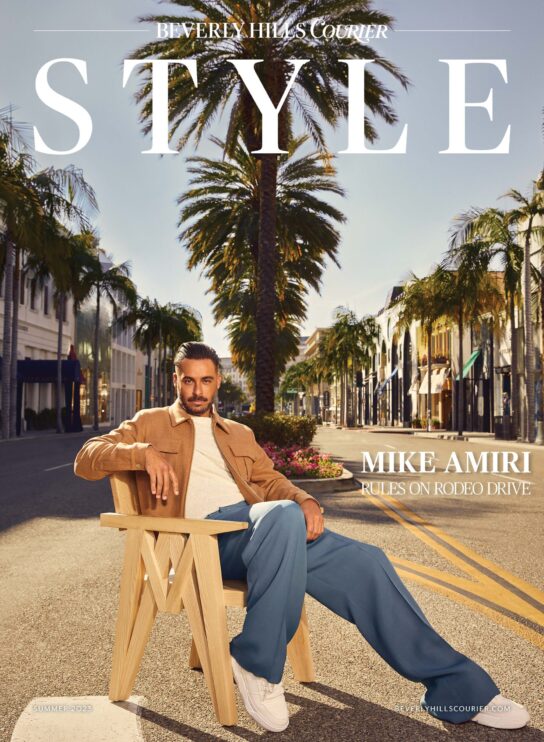

Beverly Hills Courier's Lisa Bloch on Summer STYLE 2022 | Spectrum News 1 w/ Giselle Fernández

Breaking News: Smash and Grab Robbery on South Beverly

Courier on Spectrum News 1

Anti-Maskers Protest at Hawthorne Elementary School

Follow Us On Instagram

Awards won by The Beverly Hills Courier

Awards won by

The Beverly Hills Courier

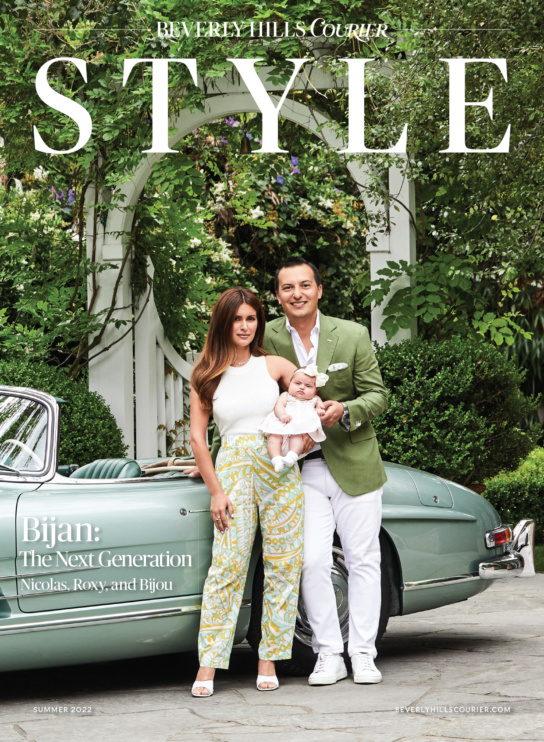

L.A. Press Club’s 2023 65th Annual California Journalism Awards

1st Place “Feature, Business/Government, over 1,000 words, Magazines”

awarded to Courier Publisher Lisa Friedman Bloch for her piece “Nicolas Bijan: The Prince of Beverly Hills”

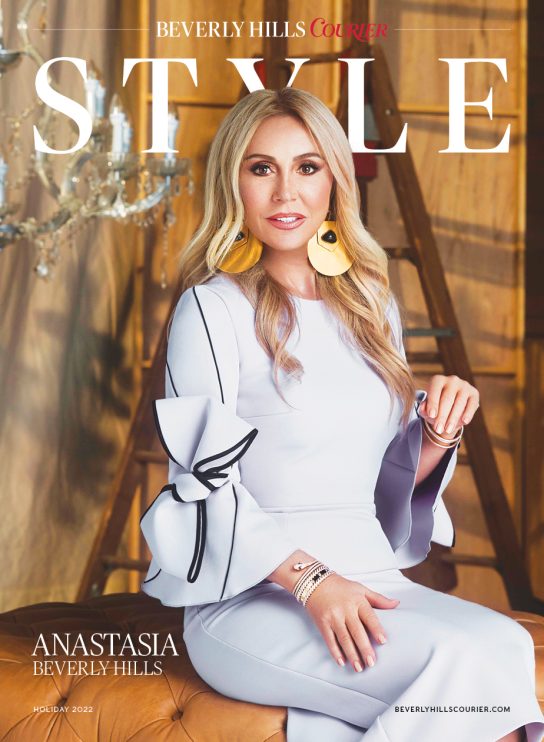

3rd Place “Personality Profile, Politics/ Business/Arts Personalities”

awarded to Courier Publisher Lisa Friedman Bloch for her piece “ANASTASIA: Beverly Hills’ World-Famous Eyebrow Queen”

L.A. Press Club’s 2022 64th Annual California Journalism Awards

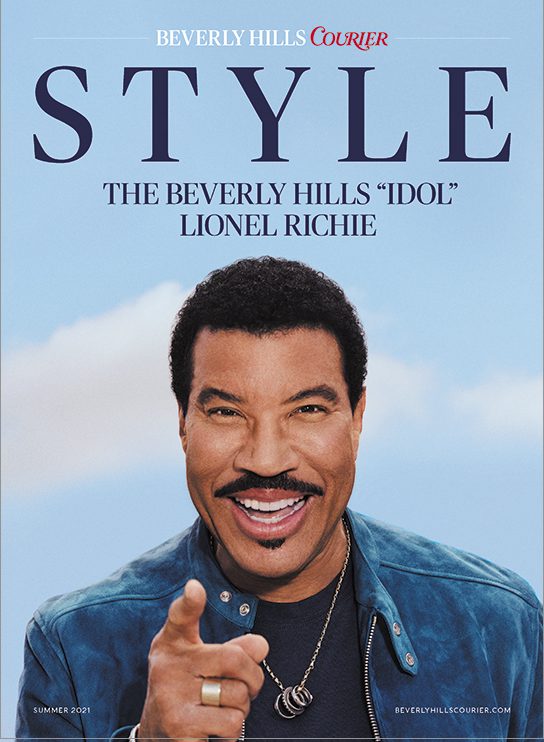

1st Place “Personality Profile-Newspapers under 50,000 in circulation”

awarded to Courier Publisher Lisa Friedman Bloch for her piece “The Beverly Hills Idol, Lionel Richie”

1st Place “Writing”

awarded to Courier Excecutive Editor Ana Figueroa for her piece “The New Audrey Irmas Pavilion Illuminates Wilshire Boulevard Temple”

2nd Place “Enterprising Reporting”

awarded to Courier Excecutive Editor Ana Figueroa for her piece “The New Audrey Irmas Pavilion Illuminates Wilshire Boulevard Temple”

2nd Place – “News Feature-Newspapers under 50,000 in circulation”

awarded to Samuel Braslow for “Beverly Hills Salon Owner Recounts Her Actions in D.C. Riot”

2nd Place “Land-Use Reporting”

awarded to Matthew Blake for his piece “Path Cleared for $1 Billion Cheval Blanc Ultra-Luxury Hotel”

3rd Place “Health Coverage”

awarded to Eva Ritvo, M.D. for her piece “From the Pandemic to Ukraine: It’s OK Not to Feel OK”

3rd Place “Writing”

awarded to Courier Excecutive Editor Ana Figueroa for her piece “200 Trunks, 200 Visionaries:

The Exhibit’ Opens on Rodeo Drive”

Photojournalism Awards – California News Publisher Association’s 2021 California Journalism Awards

3rd Place – “News Photo”

awarded to Samuel Braslow for “Protestors Confronting Schoolchildren”

4th Place – “News Photo”

California News Publisher Association’s 2021 California Journalism Awards

1st Place – “Breaking News”

awarded to Samuel Braslow for “Shooting at Il Pastaio”

1st Place – “Writing”

awarded to Samuel Braslow for “Community Rallies Around Children With Rare Disease”

4th Place – “Investigative Reporting”

awarded to Samuel Braslow for “BHPD Task Force Accused of Widespread Racial Profiling”

5th Place – “Coverage of Local Government”

awarded to Samuel Braslow for “Court Strikes Down Beverly Hills Ordinance”

California News Publisher Association’s 2020 California Journalism Awards

4th Place – “Breaking News”

awarded to Samuel Braslow for “Rally Turns Violent as Extremist Groups Take Part”

4th Place – “Protests and Racial Justice”

awarded to Samuel Braslow for “Embedded with the Beverly Hills Protestors: One Reporter’s Story”

4th Place – “Business News”

awarded to Samuel Braslow for “With No End In Sight, Restaurants Flout COVID Restrictions”